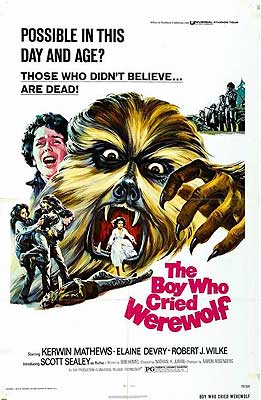

The Boy Who Cried Werewolf (1973) **

The Boy Who Cried Werewolf (1973) **

For all that I associate 1970ís horror cinema with the rise to supremacy of the new, compulsively transgressive school typified by George Romero, Wes Craven, Tobe Hooper, and David Cronenberg, the fact remains that a lot of extremely old-fashioned fright films got made during that decade, especially during its early years. The Boy Who Cried Werewolf is a case in pointó but itís also a rather curious one. This movieís traditional surface-level subject matter and downright stodgy direction (the latter courtesy of 1950ís B-movie stalwart Nathan Juran, whose final film it was) are often at odds with an up-to-the-minute subtext about the fracturing of the nuclear family. Although the old premise has been retooled to support a new theme, it simply hasnít been retooled enough to do that theme justice.

Somewhere in what I take to be the Sierras, affluent white-collar professional type Robert Bridgestone (Kerwin Mathews, from The Warrior Empress and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad) is taking his pre-teen son, Richie (Scott Sealey), up to the cabin he owns for their monthly fishing weekend. These outings appear to be a formal part of the divorce settlement between Bridgestone and his similarly affluent, white-collar, and professional ex-wife, Sandy (Diary of a Madmanís Elaine Devry), and they may actually be all that Richie normally sees of his dad these days. At the very least, we never see father and son together in any other context.

Regardless, Robert and Richie arrive at the cabin too late on Friday evening to get any fishing done before suppertime, and since neither one of them feels very enthusiastic about the TV dinners in the cabin freezer, they decide to hike down the mountain to the nearest village in search of a restaurant. What they find instead is a werewolf, which attacks Richie in a stretch of woods overlooking the state highway. Robert rushes to his sonís rescue, and acquits himself remarkably well in the ensuing battle. Itís too dark under the trees, though, for Robert to get a clear look at his opponent, so when the werewolf takes a header off the ridge and impales himself through the heart on a road sign below, Bridgestone registers only the man into which the creature transforms in death. But Richie, with his youthful eyes and his external vantage point on the struggle, recognizes the beast-man for what he really is. The admiration with which Richie extols his old manís werewolf-slaying prowess causes Robert some embarrassment the following morning, when the local sheriff (The Resurrection of Zachary Wheelerís Robert Wilke, who once played a lycanthropic monster himself in The Catman of Paris) drops by to discuss the incident, but thereís no evidence at the scene to suggest that Bridgestone acted in anything but his own and his sonís defense. Weird thing about the dead man, thoughó the county medical examiner says heís never seen, nor indeed even heard of, his blood type before.

Because this is the early 1970ís, and because Richieís parents each have more money than they know what to do with, Sandy has the boy in psychoanalysis to help him cope with the stress of the divorce. Dr. Marderosian (George Gaynes, from Altered States and Marooned), Richieís shrink, unsurprisingly has some concerns about this new werewolf fixation. As he explains to Robert, it isnít a matter of making things up, or even of an overactive imagination. Rather, Marderosian believes that the werewolf story is a defense mechanism meant to shield Richieís conscious mind against the trauma of watching his father kill a man. The boy has edited his own memories of the incident in the woods to show Robert killing a monster insteadó which is not just a permissible action, but a downright heroic one. Nevertheless, a delusion is a delusion, and the psychiatrist doesnít want to see this one take root any deeper than it already has. Marderosian recommends that Robert continue the family tradition of monthly fishing retreats, regardless of any discomfort he, his wife, or his son might feel in the wake of the attack. The important thing is to prevent the cabin and its environs from taking on an aura of the fantastic, in which Richieís delusion can grow too strong to be extirpated.

Of course we know that Richie isnít deluded at all, since the crummy day-for-night cinematography let us see the wolf man even better than Richie could. And that being so, weíll all be keeping a close watch on that bite-wound the werewolf gave Robert during their tussle on the hilltop. The injury is no longer troubling him by the time he takes Richie back to the cabin for a do-over, but the mere fact that the Bridgestonesí fishing weekends happen on a monthly schedule means that thereís a fair chance of this one coinciding with the full moon, just like the last one did. Sure enough, when Richie awakens late Friday night in response to strange noises outside, he finds his father missing from his bed. And when he goes out into the woods to find him, he comes under attack from another werewolf. Even so, Richie doesnít put all the pieces together just yet. He simply runs for his life, taking advantage of his smaller size and superior maneuverability to outdistance the creature in the densest part of the woods, then seeks shelter with a young couple (Jack Lucas and Susan Foster, of The Born Losers) on a camping trip of their own while his dad busies himself causing havoc on the road through the forest. When Robert, now back in human form, staggers into the coupleís campsite the following morning, itís natural enough for everyone (Bridgestone himself evidently included) to assume that he was human as well when he spent the whole night searching fruitlessly for his son.

Itís a different story, though, on Saturday. This time, when Robertís lupine alter ego emerges, he not only kills the two campers who helped Richie out the night before, but lugs their severed heads home with him in a knapsack. Richie first catches the wolf man attempting to bury said sack in the earthen floor of the cabin garage, and then witnesses his fatherís transformation when the dawn interrupts him in the middle of his evidence-hiding work. Thatís when the sheriff shows up, bearing news of the past two nightsí horrendous deaths. Heís proceeding on the assumption that heís got a rogue puma or grizzly on his hands, and heíd like to take a look around the Bridgestone property for any traces of such an animal. What Richie does then is surprising on its face, but becomes less so upon further reflection. While his dad listens to the sheriffís spiel, Richie scrambles to finish burying the knapsack. He may not know whatís in it, but he understands that it canít contain anything that will look good for his father.

At the same time, though, Richie just as obviously recognizes that having a werewolf for a parent is no good for him. Upon returning home from the mountains on Sunday, he wastes no time in telling both Sandy and Dr. Marderosian what Robert has become. They donít believe him, of course, or at least not literally. Sally begins to fear, though, that her own negativity toward her ex-husband is rubbing off on the boy in a way that she never intended. She therefore resolves to show Richie that the Bridgestones are still a family in spite of everything, however unlikely a reconciliation between her and Robert might remain. Take these camping and fishing weekends, for example. Next month, Sandy is going to come along, just like she would have when Richie was little, and she and Robert were still married. Iím sure putting a werewolf and his ex together for the weekend in an out-of-the-way cabin will go well for everybody, right? Marderosian, meanwhile, arrives at a more sinister symbolic interpretation of Richieís revised werewolf tales. He suspects that the transference of the beast-identity from the madman in the woods to Richieís father means that Robert has begun abusing his son! The doctor doesnít say so in as many words during his next one-on-one meeting with Bridgestone, but he lets Robert know in no uncertain terms that heís going to be watching closely for any sign of parental malpractice going forward. Thatís a recipe for trouble, too, because while Robert may not remember anything he does by the light of the full moon, the beast within him plainly has access to the manís knowledge and memories.

My favorite element of The Boy Who Cried Werewolf ends up not having much to do with anything, which is a large part of why I grade this mostly inoffensive film so harshly. No truly traditional Hollywood werewolf movie would be complete without a tribe of mystically inclined Gypsies lurking in the background somewhere, and The Boy Who Cried Werewolf amusingly updates that trope for the 1970ís by substituting a commune of nomadic hippies. These arenít just any old freaks, though; theyíre Jesus freaks, and their leader (played by screenwriter Bob Homel) seems to wield a small amount of genuine supernatural power. At the very least, Brother Christopherís blessings and invocations are potent enough wards against a werewolf, even when heís in human form. Whatís more, thatís true despite the fact that the cultís practices frequently syncretize the paraphernalia of Christian magic with that of its opposite. Witness, for example, the moment when Robert is unable to accompany Richie or Sandy into the hippiesí campsite so long as theyíre all dancing around the pentagram encircling Brother Christopherís giant cross. The film teases us throughout with the possibility that these despised oddballs (we meet them when the sheriff is trying to run them out of town for no better reason than that he doesnít like their type) will be not merely Robertís salvation, but the entire Bridgestone familyís. That would have been a much more satisfying ending, both textually and subtextually, than the one we actually get, which combines the usual killing of the tragic monster (which had come standard with lycanthropy movies since 1935) with a variant of the 70ís bummer so low-key that Iím honestly not sure director Nathan Juran fully understood what he was showing us. Not only does that ending reduce Brother Christopher and his followers to mere window dressing, but it also leaves The Boy Who Cried Werewolfís symbolic aspects unresolved. Itís enough to make me wonder if maybe a philosophical dispute arose at some point among Juran, Homel, producer Aaron Rosenberg, and Universal Pictures itself over the prospect of depicting a bunch of hippies as the saviors of the American family.

Otherwise, The Boy Who Cried Werewolf displays the plodding competency of a mid-grade 1970ís TV movie. As an aging bourgeois grouch who blames womenís lib for breaking up his marriage, Kerwin Mathews is far more plausible than he ever was as Sinbad, Gulliver, or Jack the Giant-Killer, but one still canít accuse his performance here of being memorable. Scott Sealey is no worse than any other postwar American child actor, but he isnít any better, either. Nathan Juran does neither more nor less than to get the job done, just like he used to back in the 50ís. The werewolf makeup at least is a tad better than I was expecting. Special effects artist Thomas R. Burman was one of John Chambersís many uncredited assistants on Planet of the Apes, and plainly learned a lot thereby about shifting the proportions of the human face toward the animal. On the other hand, the basic concept remains firmly rooted in Jack Pierceís work from 30 years earlier, rather than foreshadowing the markedly more bestial (and more recognizably lupine) werewolves of the decade to come. Also, itís hard to take a wolf man with so pronounced a penchant for blazers and turtlenecks altogether seriously. Rather surprisingly, the person who comes out of The Boy Who Cried Werewolf looking the best is Elaine Devry. Although her role is relatively thankless, it affords her sufficient room to play Sandy as something a little more sophisticated than the ungrateful rebel against the Natural Order of Things that Robert takes her to be, and Devry consistently exploits those opportunities for whatever theyíre worth.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact