Diary of a Madman (1963) *Ĺ

Diary of a Madman (1963) *Ĺ

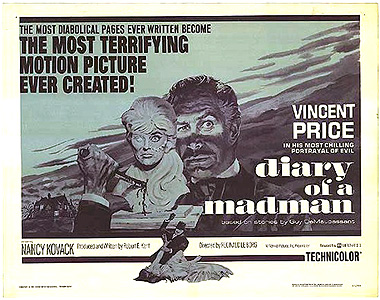

Iíve been thinking lately that itís been much too long since I saw a Vincent Price movie. He was a major fixture around here during the early days of my movie-reviewing career, to the extent that one of my first e-mails from a reader concluded, ďStrangely, I now feel an irresistible urge to watch every Vincent Price film I can get my hands on.Ē But for whatever reason, the works of Vinnie the Great havenít been falling into my lap the way they used toó my having already covered most of the really obvious ones probably has something to do with it. Consequently, I was pretty excited when I spotted Diary of a Madman in the TV schedule not long ago. I was rather less excited, however, when I watched the film, and discovered that it was one of Priceís comparatively few total stinkers.

Like the contemporary Twice-Told Tales, Diary of a Madman seems to represent an effort by a more respectable studio to horn in on AIPís Poe-movie action by casting Price in a film adapted very loosely from the work of some highly regarded 19th-century author. In the case of Diary of a Madman, the more respectable studio is United Artists (really only slightly more respectable than AIP by the early 60ís), and the 19th-century author is Guy de Maupassant, who like Poe and Hawthorne was one of the major players in the formative development of the modern short story. Also like Poe and Hawthorne, Maupassant wrote his share of horror tales, and one of those, ďThe Horla,Ē is the basis for this filmó which, in the tradition of the AIP Poe movies, bears little actual resemblance to its source.

After the funeral of Magistrate Simon Cordier, Father Raymonde (Lewis Martin, from Red Planet Mars and War of the Worlds), the officiating priest, assembles several of the dead manís acquaintances at the art gallery operated by Andre DíArville (Curse of the Undeadís Edward Colmans). DíArville himself is there, of course, as is his daughter, Jeanne (Elaine Devry, of The Atomic Kid); both of them are very up-front about their loathing for Cordier and their impatience to be done with whatever this meeting is supposed to be about. The party is completed by an old friend of the deceased, a captain of gendarmes named Robert Rennedon (Stephen Roberts, from Gog and The Twonky). The focus of the gathering is a large coffer belonging to Cordier, to which is attached a note promising a warning to mankind and a story which can be told only now that the owner of the object is dead. Inside the box is Cordierís diaryó ooh, heyÖ you donít suppose this could be that ďdiary of a madmanĒ weíve heard so much about, do you? Perhaps. The box also contains the end of the framing story, and the beginning of the movie proper.

Simon Cordier (Price) begins his diary shortly after the trial of multiple murderer Louis Girot (Harvey Stephens, from the 1959 version of The Bat). It was an odd case, with the killer confessing to his crimes, but insisting that he was not in control of himself at the time of their commission, that his hands were directed by some malevolent outside intelligence. The jury, understandably, didnít buy it, and Girot has an appointment with the guillotine in three daysí time. Strangely, however, he wants to talk to Cordier one last time before he dies, and Simon, ever fascinated by criminal psychology, is happy to oblige him. Girot repeats his story from the trial, claiming that he does so not to save his own hideó in fact, he actually wants to die, since he purports to be subject at any moment to having his body hijacked by some mysterious, murderous Otheró but to impress upon the magistrate the danger to humanity which his experiences have revealed. Girot may not know what it is exactly, but anything that can commandeer a manís will and make him a killer is something which our species cannot afford to ignore. Again, Cordier figures Girot for a loon, but then the prisonerís eyes begin glowing green and he lunges at Cordier, evidently intent upon strangling him. A short struggle ends with Cordier cracking Girotís head against the stone wall of his prison cell, and the condemned man dies a moment later.

Over the next several days, Cordier canít seem to get his mind off of Louis Girot, and strange things begin happening whenever his thoughts turn in that direction. He finds the record of the Girot trial sitting on his desktop when he has no memory of ordering it pulled, only to see the transcript ruined as his inkwell seemingly upends itself of its own volition; immediately thereafter, the window to Cordierís office bursts open, again without any apparent cause. Meanwhile, at home, a portrait of Cordierís dead wife and son hangs in its formerly accustomed place on the wall of his study, despite having been removed and locked away in the attic some twelve years ago. Neither Pierre the butler (Ian Wolf, of Mad Love and THX-1138) nor Louise the maid (Blood of Draculaís Mary Adams) will admit to bringing it down, and when Cordier returns the painting to the attic, he sees a quote from some of Girotís ramblings traced in the decade-old dust. The message is gone a moment later, however, when Simon calls Pierre up to the attic to see it. Finally, these tired retreads of Gaslight are kicked to the curb, and Cordier begins hearing a voice (that of Joseph Ruskin) claiming to belong to Girotís bloodthirsty possessor, which announces that it will be taking over Simon in the dead manís place. The voice explains that it is a Horla, an invisible being from a plane just slightly out of phase with our own, able to cross the boundary between dimensions whenever it encounters a sufficient concentration of human evil. In Cordierís case, or so the Horla would have it, that evil was manifested when he drove his wife to suicide, blaming her for the death of their son. And just to prove to Simon that it isnít fucking around about using the magistrateís body as an instrument of violence, the Horla possesses Cordier for just long enough to make him crush his beloved pet canary to death in his hand.

The next day, Cordier goes to see a psychiatrist. I expect you would too. Dr. Borman (Nelson Olmstead) believes Cordierís problem is that he has immersed himself too completely for too long in the guilt and loneliness attendant upon the deaths of his family. The magistrate needs to get out and live a little! Simon used to be a sculptor of some renown; Borman suggests that he resume his old avocation, and start circulating within the vibrant Paris art scene once again. Give himself an outlet for his mental energies; meet some new people; hell, maybe even get himself laid. Even if it isnít precisely the cure for what ails him, it certainly couldnít hurt anything, right?

If the trouble really were all in Cordierís head, then Bormanís prescription would probably be right on the money. But since Simonís problem is not incipient madness, but incipient possession, the real effect of getting him out of the house is to bring him into contact with all the potential victims the Horla could ask for. On the afternoon following his visit to the psychiatrist, Cordier stops in at the Gallery DíArville, where he spies a painting of a beautiful woman in a ballerinaís costume. The artist, Paul DuClasse (Chris Warfield), has a number of pieces on display at the gallery today, and whatís more, Odette Mallotte (Nancy Kovack, from Jason and the Argonauts and Marooned), the model for the ballerina painting, is in attendance. She chats Simon up in the hope of getting him to buy her portrait, but instead, her flirtatious sales pitch brings about a slightly different result, and he hires her to model for his own sculptures at the impressively generous rate of ten francs per hour. Cordier has misunderstood the situation, however. Odette is married to DuClasse, and had previously agreed to pose henceforth only for him. But the couple need the money badly, and since the going rate for Paulís paintings seems to be well below the cost of producing them in the first place, the artist doesnít have a whole lot of room to argue. Matters become even more complicated once Odette arrives at Cordierís mansion for her first sitting. Whatever her feelings for her husband, Odette is a gold-digger first and foremost, and Simon Cordier makes a much more tempting target for avarice than Paul DuClasse. Paulís best friend, Jeanne DíArville, obviously sees Odette for what she really is, and wishes Paul would get the hint and set his sights on her instead. And the Horla, meanwhile, thinks it would be buckets of fun to force Cordier to kill his adulterous new girlfriendó especially since the otherworldly assassin could get two for the price of one if it plays its cards right, framing DuClasse for the crime. But no matter what the Horla can make Cordier do, it canít alter the magistrateís sense of right and wrong, and Cordier might just get desperate enough to do something really drastic to free himself of the creatureís hold. In fact, since the movie began with Simonís funeral, Iím thinking we can pretty much count on it.

Diary of a Madmanís most serious shortcoming is that it manages to seem extremely preachy without having any particular sermon in mind to preach. Moments like the scene in which Cordier attempts to kill Jeanne, but is snapped out of his trance by the sight of a cross reflected in the blade of his knife, or like any of the outwardly purposeless arguments between Cordier and Captain Rennedon over the value of criminal psychology, make it seem pretty clear that either writer Robert E. Kent or director Reginald Le Borg had some kind of axe to grind, but itís hard to imagine what that might be. Evil is Bad, maybe? Or perhaps Evil Brings Its Own Punishment? Hardly seems like a theme worth belaboring, does it? And even if it did, the storyline here doesnít line up with it all that well. I mean, the Horla has no discernable motive for its behavior, and itís difficult to credit its assertion that it was called into our world by Cordierís cruelty to his wife, given both that said cruelty occurred twelve years ago and that Cordier is the creatureís second host on this plane at least. But then, I suppose it hardly pays to expect much in the way of lucidity from a film called Diary of a Madman, which makes it plainly apparent less than half an hour in that the ostensible ďmadmanĒ is in fact completely sane. The movie also suffers from mostly woeful acting and absolutely putrid dialogue. Most of the performers seem to be completely unaware that the story is supposed to be set in 19th-century Paris, a point to which Vincent Price calls the maximum possible attention by being the only one of the bunch to give the names of people and places their proper French pronunciations. Chris Warfield in particular makes for quite possibly the least persuasive movie Frenchman of all time. Stephen Roberts isnít much more impressive, but his inadequacies are at least forgivable. Roberts has little to do beyond walking into the room to ask Price, ďSo youíre still interested in studying the criminal mind, are you?Ē over and over again, and nobody could deliver that line convincingly more than once. The saddest failure is that of Price himself, though. He certainly tries, but the role gives him nothing to grab hold of. He canít very well aim for a good performance with every word of dialogue falling down dead the moment it leaves his mouth, but the character of Simon Cordier gives no opportunity for Priceís trademark thunderous hamming, either. Basically, Price shows up, does his job, and collects his check, bringing nothing to the film outside of his marquee value. If the aim really was to cash in on The Fall of the House of Usher and its successors, then United Artists didnít understand what made those movies work any more than MGM did.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact