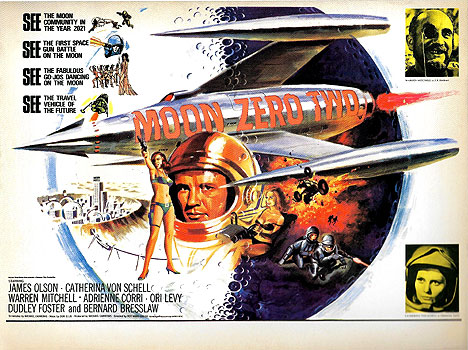

Moon Zero Two (1969) *½

Moon Zero Two (1969) *½

For all that Hammer Film Productions is primarily remembered as a horror studio, they made some awfully impressive science fiction movies as well during the 50’s and 60’s. On the other hand, the best of Hammer’s efforts in the latter genre— the Quatermass trilogy, These Are the Damned, The Abominable Snowman— could just as fairly be described as fright films in sci-fi drag. The company’s forays into pure science fiction are less highly regarded, and in the case of Moon Zero Two, the disdain is amply justified. A competently mounted but lethally boring confection of repurposed Western clichés, Moon Zero Two serves mainly to demonstrate that nobody at Hammer understood what had made 2001: A Space Odyssey such a big hit, however eager studio boss James Carreras might have been to carve out a piece of that action for himself.

Oh— and Moon Zero Two is an intensely uncharacteristic movie for Hammer, tonally speaking. The first indication of its peculiarity comes in the form of an animated opening credits sequence that recalls nothing so much as the cartoon primer on the Cuban Revolution which kicks off Creature from the Haunted Sea. If we’re to take it at anything like face value (none of this stuff will ever be mentioned again, so it’s difficult to be sure whether we should), the space race between the Cold War superpowers quickly devolved into a comedy of errors in which each side was so determined to obstruct the other’s efforts that they never managed to accomplish much of anything for themselves. The way was therefore left open for other nations— the United Kingdom, for example— to create vibrant, thriving lunar colonies untroubled by geopolitical dick-measuring. By the year 2021, when this picture is set, the British sector of the Moon is like a Wild West frontier town complete with homesteaders, claim-jumpers, and saloon girls, only as imagined by Antonio Margheriti after binge-watching the entire James Bond franchise.

Among the less shady of the shady characters drawn to the pop-art-flavored semi-anarchy of Her Majesty’s Moon are a pair of partnered space pilots (ambiguously gay connotations of “partnered” very much intended by me, albeit not by the filmmakers themselves— longing looks in the locker room notwithstanding) named William Kemp (James Olson, of Amityville II: The Possession and The Spell) and Kominski (Ori Levy). Kemp and Kominski seem constantly to be on the verge of getting into serious trouble with space sheriff Elizabeth Murphy (Adrienne Corri, from A Clockwork Orange and Sword of Lancelot), but slipping free at the last minute in part because Murphy has the hots for Kemp. Truth be told, William would really like to go straight, but having been forced out of Her Majesty’s NASA (still a source of considerable resentment for him), piracy is basically the only way he can earn a living doing what he’s good at.

Kemp’s latest effort to do things on the up-and-up goes awry when he’s offered two gigs that add up to one giant conflict of interest. On one side is an attractive young woman newly arrived from the homeworld, by the name of Clementine Tamplin (Catherine Schell, from Lana, Queen of the Amazons and Traitor’s Gate). Her brother was a lunar frontiersman who dropped out of sight just as his moonstead was starting to be worth something. Now Clementine has come in person to investigate the disappearance, but she’s on a tight schedule for doing so. In order to discourage rentiers from buying up Moon land and sitting on it, the laws governing moonsteading stipulate that unworked, unimproved, or uninhabited tracts revert to the Crown after a certain period of time, becoming available for re-lease to other claimants. Clementine’s missing brother is just days from reaching that limit, and his territory is all the way over on the Moon’s far side. She can’t afford to wait for a more reputable pilot than Kemp to take her there for her amateur sleuthing.

Meanwhile, Kemp and Kominski are also being courted by skeezoid business magnate J.J. Hubbard (Warren Mitchell). Hubbard has a plan to get even richer than he already is, but it’s even less legal than whatever he did to make his first few fortunes. You see, there’s an asteroid due to pass by the Moon in a few days, and a scientist on Hubbard’s payroll has determined that underneath its dusty exterior, that rock is practically pure sapphire. Although most people naturally think of sapphire as a gemstone, it’s also an important material in space-related industries; there’s nothing quite like it for shielding solar cells from harmful cosmic rays while still letting in the light they need in order to function. If Hubbard sent a team up to the asteroid to harvest the sapphire in situ, all manner of international conventions on interplanetary salvage would eat into his profits. But if he could divert the whole mass far enough off course that it crashed into the far side of the Moon, he could then secure the lease on its landing site, and own the coveted rock free and clear. Hubbard’s dour henchmen, Harry (Bernard Breslaw, from Blood of the Vampire and Krull) and Whitsun (A Study in Terror’s Dudley Foster), have the necessary demolitions expertise to plant the orbit-perturbing bombs, but they’d need a good pilot to get them to the asteroid without attracting attention— and obviously Hubbard can’t go to a pilot whose licenses are all in good order for a job like this. Kemp, though? This sort of thing is right up Kemp’s alley.

As for the conflict of interest, it comes to light when William discovers that the land where Hubbard proposes to crash his asteroid is the very same plot that the vanished Mr. Tamplin had been developing. Since the businessman’s plan hinges upon ownership of the land where the rock comes down, that obviously makes Hubbard the prime suspect should it turn out that there was foul play involved in Tamplin’s disappearance— and what Kemp and Clementine find on the abandoned moonstead certainly looks like foul play. The trouble, inevitably, is that there’s no proof of anything. The Moon is a hostile environment, after all, and people die there unexplainedly all the time. If Kemp really wants to help Clementine, he’ll have to go through the motions of his deal with Hubbard even despite what he now suspects, spending a lot more time with Harry and Whitsun than is likely to be good for him.

Roy Ward Baker was one of Hammer’s most capable latter-day directors, and his previous sci-fi film, Five Million Years to Earth, was one of Hammer’s most effective latter-day productions. Furthermore, Moon Zero Two shows every indication of having benefited from the examples of previous 60’s space operas ranging from “Star Trek” to The Wild, Wild Planet. It’s an often gorgeous movie, even if it sometimes prefigures the dismal beige-and-gray palette of “Space 1999” a little too strongly. Esthetically, the operative theory seems to have been, “Let’s make a whole movie as a Swinging London version of 2001’s Pan Am Spacelines sequence.” Another example from which Moon Zero Two even more clearly benefited was that of the real-world US space program. When Baker shows us a lunar lander or a moon buggy, it’s generally just a slightly fictionalized version of something NASA was actually using. And finally, this movie goes out of its way to emphasize how thoroughly inimical to human life the Moon is as an environment. On paper, Moon Zero Two ought to be quite an impressive film on the merits, even if Hammer was caught flat-footed by the past two years’ momentous developments in both science and science fiction.

So why is it instead such a dreary chore? A lot of it is a matter of energy level. In a bit of self-referentiality it could have done without, Moon Zero Two as a whole has the demeanor of a stock cowboy hero who spends his time between gunfights leaning against saloon walls, never saying anything more involved than “No, ma’am” or “I reckon so.” Even with notionally urgent deadlines and lethal conspiracies hanging overhead like so many Swords of Damocles, Baker never sees fit to accelerate past an easy amble. Bernard Breslaw’s Harry is the only one who seems really invested in the proceedings, and to judge from the look perpetually etched across his face, he’d be content to match the passivity of his fellows if he could just figure out who keeps farting on the set. And worst of all— although this is as much a problem all its own as it is a manifestation of Moon Zero Two’s laconic lethargy— the several screenwriters seem to have considered their job done once they’d devised plausible lunar counterparts for all the items on some master checklist of Western commonplaces. I guess I need to give them some credit, though, for putting more emphasis on the “plausible” in that sentence than, say, the folks behind Outland. Still, everything that happens in Moon Zero Two just feels so fucking weary, despite the change of venue. As far out of touch as Hammer’s horror films would fall in the decade to come, that misjudging of the zeitgeist has nothing on offering up this clunker as a bid to cash in on 2001.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact