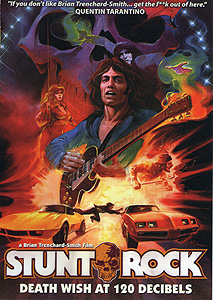

Stunt Rock / Crash / Sorcery (1978) **½

Stunt Rock / Crash / Sorcery (1978) **½

I didn’t say it; Brian Trenchard-Smith did: “In this business, every now and again a filmmaker gets a wild-arse idea, and there is a system of development and creative executives at various levels that are in place to prevent such an idea from ever reaching the screen. In this instance, the system failed.” The wild-arse idea of which he speaks is Stunt Rock, arguably the climax of his decade-plus-long campaign to make a full-fledged movie star out of stuntman Grant Page. Trenchard-Smith had always harbored a fascination with stunts and stunt performers, from his daredevil childhood, through his adolescence as a film hobbyist making short subjects organized around chases, falls, sword fights, and the like, to his professional career as one of the leaders of Australia’s exploitation movie industry during the boom years of the 70’s and 80’s. He was the one who allied with Hong Kong’s Golden Harvest studio to produce and direct The Man from Hong Kong (the martial arts espionage thriller that famously concludes with George Lazenby kung fu fighting while on fire) and Kung Fu Killers (a television documentary about the ultimately unsuccessful and in any case irrelevant search for “the next Bruce Lee”). He sent the Australian post-apocalypse action flick out with a bang in Dead-End Drive In. And most directly relevant to our present purposes, Trenchard-Smith established what would remain practically a one-man genre with a string of what might best be called stuntsploitation pictures: The Stuntmen, Deathcheaters, Dangerfreaks, etc.

No, wait— that isn’t quite right. Stuntsploitation in the specifically Trenchardian sense was always a two-man genre, for Trenchard-Smith could never have done it without Grant Page. You may not know Page by name, but if you’ve ever seen an Australian movie that involves high falls, car crashes, or people doing things while on fire, there’s a better-than-even chance that he was involved somehow or other. He was the stunt coordinator for Mad Max and Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome. He was the burning guy jumping out of the cliffside lake to attack a dreaming Dennis Hopper in Mad Dog Morgan. He managed everything and everyone that caught on fire in The Day After Halloween. Page came to Trenchard-Smith’s attention on the set of The Stuntmen, for which he had been hired as merely one largely unknown daredevil among many. It was immediately obvious that he was in a class of his own, though— not just seemingly without fear, but also a gifted strategic thinker, a natural master of risk management, and a possessor of rockstar-caliber charisma. Smitten, Trenchard-Smith offered to become Page’s agent for five years, vowing that by the end of that term, Page would be starring in movies, and not just risking death and dismemberment in them. Obviously there was considerable advantage for Trenchard-Smith in the arrangement, too, because being Page’s manager would give him first crack at hiring him, for exactly the sort of films that the director-producer most enjoyed making.

Stuntman to movie star is not a transition for which there’s a lot of precedent, though, so it’s only to be expected that the pair would try several different approaches to achieving it. The Stuntmen had been a behind-the-scenes look at the titular profession and its role in the cinema industry, and the first fruit of Operation Make Grant Page Famous was in much the same vein. Trenchard-Smith cast him as the host of Kung Fu Killers, sending him to Hong Kong to observe and interpret the world of Asian martial arts films, of which Western moviegoers were for the most part just barely aware in the mid-1970’s. Next came small character parts in The Man from Hong Kong and Mad Dog Morgan (the latter was Page’s first acting gig in a film not produced by his benefactor), both of them projects on which Page could make conspicuous use of his primary talents as well. The real watershed, though, was 1976’s Deathcheaters; here was the promised starring role for Page, and not just in a documentary context. Deathcheaters might usefully be thought of as the Australian counterpart to Viva Knievel!, in that it features Page as a thinly disguised version of himself who gets caught up more or less by accident in a standard action-movie caper tale that just happens to require frequent recourse to behavior like driving insanely, jumping off of very tall things, and climbing up the outsides of buildings. Then the Grant Page stardom project took a turn for the truly bizarre.

Yes, I’m finally returning to the subject of Stunt Rock. As I said, Page’s charisma was decidedly of the rockstar variety, and perhaps that was the seed from which the notion sprang one morning when Trenchard-Smith found himself overcome in mid-shower by a scheme to team Grant Page up with a famous American rock band. As soon as he finished drying himself off, Trenchard-Smith did what nearly any independent filmmaker would probably have done under the circumstances in 1977— he smoked a joint and sat down to write. The resulting six-page treatment eventually found its way to the desk of Dutch producer Hermen Ilmer, who saw even greater potential in it than its author. Trenchard-Smith had been thinking in terms of a modest, Sydney-based production using local talent apart from the as yet unchosen band, but Ilmer worked out a deal to shoot in Los Angeles (albeit with a non-union cast and crew), and to bring along Monique Van De Ven, then one of the most popular and respected actresses in the Netherlands, to play the female lead. Ilmer also had high hopes for the musical angle, promising to get somebody truly top-shelf to handle the “rock” side of the Stunt Rock equation.

Reality, perhaps not surprisingly, had other plans. Again I quote Trenchard-Smith: “I’d been promised, ‘Yeah, we’ll get you Kiss… we’ll get you the Eagles… we’ll get you etc.’ But then it turned into, ‘Well, find a band by Monday, or we shut down the picture.’ So I found a band that you find by Monday.” Note, however, that Sorcery’s status as “a band that you find by Monday” did not mean that the director was unhappy or disappointed to have them. Far from it, in fact. When Trenchard-Smith saw a videotape of one of their live sets, he recognized at once that they were a far better choice, thematically speaking, than any of the A-listers (including Van Halen!) to whom Ilmer had unsuccessfully offered the gig. That’s because Sorcery were no ordinary hard rock group. Like a lot of their contemporaries, they went to great lengths to put on a show that no mere studio album could adequately capture, providing a powerful extra incentive to their fans to pony up for concert tickets. Pink Floyd had their laser light show; Kiss had their costumes, makeup, and pyrotechnics, and Gene Simmons puking stage blood at the audience; David Bowie had whatever crazy-ass identity-reinvention thing he was working on that week. What Sorcery had was a live magic act, in which the band’s performance served as a backdrop to illusionary combat between the King of the Wizards (Paul Haynes) and the Prince of Darkness (Curtis Hyde). So basically, they had one guy dressed up as a 70’s van-art interpretation of Merlin and another guy dressed up as the Devil (or perhaps as “Star Trek’s” Chancellor Gowron without the forehead prosthesis) charging around the stage, shooting gouts of flaming propane at each other and making each other disappear. Obviously they were perfect.

The question remained of how to contrive the match-up between Sorcery and Grant Page, and the approach ultimately taken by Trenchard-Smith and his co-writer, Paul-Michel Mielche Jr., may surprise you with its combination of naïve artlessness and sheer minimalism. Stunt Rock posits that Page (explicitly playing himself this time) has been hired as stunt coordinator for an American television series called “Undercover Girl,” which inexplicably stars Monique Van De Ven in the central role as a sort of one-woman Charlie’s Angels. Upon arriving in LA, Grant is picked up at the airport by Curtis Hyde, of all people— whom Stunt Rock ludicrously attempts to pass off as his cousin! Curtis introduces Grant to Paul Haynes and the rest of the band: vocalist Greg Magie, guitarist Richard Taylor (who was calling himself “Smokey Huff” in those days), bassist Richie King, and drummer Perry Morris. There’s also a mysterious keyboard-player named Doug Loch, who wears a luchador mask at all times and speaks in an affected cartoon-character voice; Loch wasn’t a member of Sorcery in the real world, but since the studio recordings that the movie would use to represent their performances featured a keyboard track, the band wanted to make sure somebody was up on the stage to account for it.

There really isn’t a plot as such. Page does his thing on the “Undercover Girl” set. Sorcery play flatulent, boring prog rock while the magicians launch fireballs all over the place. Everybody does Hollywood stuff like hanging out in recording studios and going to schmoozy parties at agents’ houses. (The escape artist who appears out of nowhere in the party scene, and is then never so much as mentioned again, is Chris Chalen, a friend of Greg Magie’s who introduced the musicians to Haynes and Hyde.) Every ten minutes or so, somebody will ask Page a question that the film answers with a clip from some other movie: The Stuntmen, Kung Fu Killers, The Man from Hong Kong, Mad Dog Morgan, Deathcheaters— even Gone in 60 Seconds for some reason, even though Page had nothing to do with that one so far as I can tell! The only hints of story-generating conflict are relegated to a pair of subplots which never get properly resolved anyway. One of these concerns the ongoing struggle between Monique and her smarmy agent (Don Blackburn) over the issue of (surprise, surprise) stunts. Monique wants to perform her own on “Undercover Girl,” but the agent says it’s too dangerous for a big star like her. In the other, Grant becomes romantically entangled with a reporter for Tempo Magazine (Trenchard-Smith’s wife, Margaret Gerard), who enters the picture via a story she’s writing on people who are into their jobs with an intensity that most folks would consider insane, and then spends half her screen-time bellyaching over the possibility of Page getting himself killed. Stunt Rock almost does the sensible thing at one point by having Page teach Haynes and Hyde a few new tricks to punch up their act, but then the writers think better of it and drop that angle. In the end, when Page finally joins Sorcery onstage, he does so in a way for which no groundwork has been laid whatsoever.

Stunt Rock didn’t exactly live up to anyone’s expectations of it, at least commercially speaking. It cost too little to be a true flop, and it gradually amassed a modest international cult following both for itself and for Sorcery, but Margaret Gerard’s final line predicting revolutionary pop-culture impact for the fusion of stunts and rock (and by extension for Stunt Rock) must have sounded ridiculous within a matter of weeks. Honestly, it’s hard to see how it could have been any other way. Trenchard-Smith himself forthrightly describes the movie as “largely plotless” and “a 90-minute trailer,” but the point of reference that jumps immediately out at me is if anything even more damning: Stunt Rock is the cinematic equivalent of one of those godawful clip episodes that TV shows used to slap together whenever they were running behind schedule and over budget for the season. Except for the absurd Sorcery performances, there’s very little original to this movie, and most of what there is serves mainly as a jumping-off point for stock footage.

Despite all that, however, Stunt Rock can be surprisingly entertaining on an “Oh my God! Look at all the crazy shit these people are doing!” level, and because that is exactly the level on which Brian Trenchard-Smith meant for it to operate, it must therefore be classed as at least a partial success. Grant Page deserves every ounce of the director’s obvious, fawning admiration and then some, even if the star-making initiative was probably a fool’s crusade from the outset. I don’t know to what extent Page’s dialogue for the scenes in which he explains the science and philosophy of stunt performance was scripted by the writers, or how much of it was him repeating his standard answers to what have to be pretty commonplace questions for an entertainer in his line of work, but either way, it conveys the impression of affording us a peek inside an extremely interesting head. Sorcery, meanwhile, come across as such earnest doofuses that it’s impossible not to like them, however terrible their music may be. Stunt Rock isn’t really a film that rewards close attention, and the tale of its unlikely genesis is more compelling than anything that wound up on the screen, but if you’re in the market for a movie you can leave on in the background at your next party, you could do a lot worse than it for captivating the occasional five or ten minutes of the guests’ attention.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact