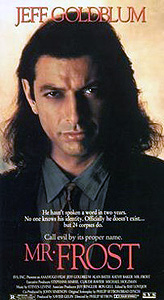

Mr. Frost (1989) ***½

Mr. Frost (1989) ***½

Most dedicated movie fans can point to a few films somewhere on their second or third tier of favorites that they relate to as their own personal discoveries. These are movies with no well-known reputation to precede them, and which relatively few people seem to have seen. Nobody told us to check these movies out, nor were we turned on to them by a high-profile advertising campaign. For the most part, we’re not talking about really brilliant films here— otherwise, they’d almost certainly be more widely known than they are— but they’re pretty goddamned good, and those of us who have discovered them can’t for the life of us imagine how they slipped through the cracks so completely. For me, Mr. Frost is one of those movies. I blundered into it on cable completely by accident one night, and it hooked me almost immediately. And while it’s true that there are a number of things about it that don’t quite work, it certainly deserves far better than to languish in sun-faded boxes on the “suspense” or “thriller” shelves of struggling mom-and-pop video stores that nobody much ever rents from anyway.

Somewhere out in the English countryside, a pair of young men ride double on a motorcycle to the grounds of a huge, isolated mansion. The two lads are car thieves, and they have come to relieve the mansion’s owner of his bright red Aston-Martin. The thieves are successful in sneaking into the garage, and have so lucked out that the car’s doors aren’t even locked. They lose their appetite for burglary, though, when they open up one of those doors, and a dead body falls out onto the concrete floor of the garage.

A day or two later, Police Inspector Felix Detweiler (Alan Bates) stops in at the mansion to have a chat with its owner, the eccentric Mr. Frost (Jeff Goldblum, from The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai: Across the 8th Dimension and David Cronenberg’s version of The Fly). Frost is working in his garden when Detweiler arrives, and he seems strangely incurious about what has brought the detective to his house. He invites Detweiler inside, offers him a serving of the baked Alaska he has just taken out of the oven (when Detweiler declines, Frost tosses the dish in the garbage after taking a Polaroid photo of it), and sits down in the living room with the inspector. Detweiler somewhat haltingly explains that he has come because his office has arrested the thieves from the previous scene, and they told him about the body they supposedly saw in Frost’s car. Frost’s response leaves Detweiler as stunned as if he’d been slapped in the face: “Oh, the body! I was just burying that in the yard when you came. What? You think I’m kidding?” Detweiler and Frost agree that the detective should stop by the next day with a warrant to search the mansion.

When he does, Detweiler finds far more than one body in buried in the garden. His men have dug up a dozen so far, but Frost himself claims that the remains of 24 men, women, and children are out there someplace. He also hands Detweiler a videotape that shows him torturing some of his favorite victims to death. The surprises continue after the arrest. Evidently, Frost has left absolutely no paper trail behind him. He has no driver’s license, no passport, no voter registration or tax documents— not even a birth certificate! Officially speaking, he may as well not even exist. And because he refuses to say a word to anyone about anything from the moment he is taken to jail, the men investigating his case can’t even turn to him to fill in the gaps. Frost is found insane by the court that tries his case, and he is packed off to a succession of mental hospitals, some in Britain, some in Continental Europe.

Two years later, Frost is transferred to the Ste. Claire Psychiatric Hospital, somewhere in France. Head psychiatrist Dr. Raymond Reynhardt (Roland Giraud) is bursting with excitement at the possibility that he and his team will be the ones to finally solve the mysteries surrounding the famous Mr. Frost, but the doctor has much more on his hands than he bargained for. There is a breakthrough, in that during his introductory meeting with the Ste. Claire staff, Frost speaks for the first time in two years. But he will speak only to Reynhardt’s subordinate, Dr. Sarah Day (Kathy Baker, of Edward Scissorhands), and everything he says to her at this first meeting is openly disparaging of Reynhardt himself. The doctor doesn’t really mind, though; he figures he’ll just use Day as his proxy in Frost’s treatment. Frost has other plans, however. After that first time, he refuses to so much as open his mouth as long as anyone but Day is within earshot, be they Reynhardt and his fellow doctors eavesdropping from behind the mirror in the interview room or even just one of the orderlies. Reynhardt will just have to accept the fact that Frost wants Dr. Day in the driver’s seat for some reason.

Frost has one hell of a reason, as it happens. No sooner has he forced his doctors to let Sarah Day talk to him alone than he lets her in on a little secret. That strange business about Frost having left absolutely no official record of his existence? It’s because (or so he claims) there’s no such person as Mr. Frost at all. He’s really the Devil, and he’s stopped in on Earth to prove a point. What rankles the Prince of Darkness so much that he has put in a personal appearance among mortals is the fact that modern Western science has done so much to erode belief in him. As he says— with a distinct note of incredulous nostalgia in his voice— “People used to sell their souls!” And so, basically to prove to himself that he’s still got it in him, Satan has taken on the guise of a human being, and embarked on a quest to take the most hard-headed, scientifically oriented, secularist skeptic he can find, and make him or her believe in Evil with a capital “E.” Step one was to commit a string of shockingly horrible and utterly inexplicable crimes. Step two was to turn himself into a trophy patient, the kind any ambitious and accomplished psychiatrist would do just about anything to get a crack at. Step three is going to be the fun part. Frost asks Day what would be the worst thing a psychiatrist could possibly do, the one totally unforgivable act that would put a person in her profession entirely beyond the pale for the rest of his or her life. When Day seems stumped, Frost answers his own question for her: murdering a patient. This is the real point of Frost’s game. He means first to convince Day that he really is the Devil, then to convince her that the only way to stop him from carrying out an escalating series of very bad deeds is to kill him herself. To Day’s ears, of course, all this sounds like nothing more than an especially intricate delusion. The thing is, though, it looks like there’s a good chance Mr. Frost is telling the truth...

Mr. Frost could easily have wound up being nothing more than a cheesy, belated rip-off of The Omen. Alternately, it might have turned out as something like an Anglo-French The First Power, which, after all, also focused on a serial killer with Satanic connections. Luckily for us, that's not what happened, though. On the one hand, Frost’s killing spree is treated entirely as back-story, leaving no room for a cops-vs.-demonic-killer plot on the model of William Peter Blatty’s wretched Exorcist follow-up, Legion (eventually, pointlessly filmed as Exorcist III: Legion). On the other, the film’s several writers devoted far more energy to the duel of wits between Frost and Dr. Day than to the expected routine of conspicuous diabolic intervention in the affairs of men. I’d have preferred a bit more ambiguity regarding the final answer to whether or not Frost truly is the Devil, but since that question isn’t really director Philip Setbon’s primary concern, the movie doesn’t suffer too much from its excess of forthrightness.

No, what Setbon and company are interested in is their distinctive characterization of Satan, and it’s that— combined with Jeff Goldblum’s spot-on performance— that really makes Mr. Frost shine. There is no trace of Milton in Frost, nor of any other previous cinematic take on the Devil’s personality that I’m familiar with. Instead, Mr. Frost presents an intriguingly diminished Satan, insecure about his future in a world where humankind has increasingly little inclination to interpret life in terms of a cosmic struggle between Good and Evil. Setbon’s is a neurotic Satan, but also a Satan with a sense of humor. Furthermore, this movie focuses on an aspect of the scriptural Devil that one almost never sees in film— Mr. Frost's Satan is also Job’s Satan, the Satan who makes bets with God as a way to test his own power. All in all, it is easily the most thoughtful and thought-provoking portrayal Lucifer had received from a filmmaker in at least a decade. It’s also a characterization that suits Goldblum perfectly, and it’s no wonder that he should dominate the film so completely.

That said, I must admit that Mr. Frost is basically a one-man show. None of the other characters— not even Sarah Day— are as fully developed as they ought to be, and as a result, the movie ends up having more intellectual interest than emotional impact. Even when her favorite patient escapes from the hospital and goes on a God Told Me To-like shooting spree at Frost’s incitement, Kathy Baker doesn’t seem nearly as upset as she should, and the gradual wearing down of her disbelief in Frost’s literal diabolism is only imperfectly convincing. But even so, there is so much right about Mr. Frost that I’m willing to forgive even a few relatively major screw-ups.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact