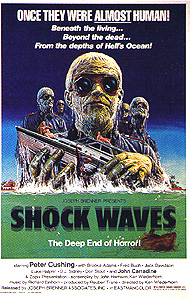

Shock Waves / Death Corps / Almost Human (1977) ***½

Shock Waves / Death Corps / Almost Human (1977) ***½

Years and years ago, around the time when my family first purchased its first VCR, there was a little mom-and-pop video store in Bowie called Plus Video. Plus (or Metro, as it was later known) was always a good bet for obscure, unusual films, and because I was already a big fan of the obscure and unusual back in the mid-1980’s, it was one of my favorite places to go looking for movies to rent. One of the first tapes I rented from Plus (I can no longer remember what the movie was) had a pair of trailers at the beginning, and both of them had me saying, “Man— I’ve got to see that!” The first trailer was for Dominique is Dead, which I still haven’t seen more than a decade and a half later. The second was for Shock Waves/Death Corps/Almost Human, and that movie I tracked down right fucking quick. (It was easy enough— Plus happened to have a copy.) All I could say after watching it was, “Wow.” And though the current state of my taste demotes that to a qualified “wow,” the gist of my reaction remains the same. Most of the obvious positive things to say about Shock Waves sound suspiciously like damning with faint praise. You could call it “the best horror movie ever made in Florida,” but, while true, that wouldn’t exactly make a convincing case for why a person should want to see it. Ditto for saying it’s “the best of the Nazi zombie movies.” Even something like “as good a first feature as anyone has ever made with so little money” carries a distinct whiff of warning. No slight or warning should be inferred from any of those descriptions, however. Shock Waves is an extremely good film, in ways you'd never dare expect on the basis of its subject matter.

As we begin, three separate vacations have come together in what will prove to be an unfortunate conjunction. Rose (Brooke Adams, from the 1978 version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers and the 1971 version of Murders in the Rue Morgue), Chuck (Fred Buch), and argumentative married couple Norman (Jack Davidson) and Beverly (D. J. Sidney) are all out on a diving tour somewhere in the Caribbean aboard the hire-boat Bonaventure. Both the boat and its captain (John Carradine, of Billy the Kid vs. Dracula and The Wizard of Mars, looking as though he's about 8000 years old) have seen better days, and the vessel has broken down in a patch of sea above (though no one aboard knows this, of course) the wreck of a transoceanic freighter. All three members of the crew are busy just now trying to get the engine started again, while Rose goes for a swim in the surrounding ocean. Captain Ben and his mates, Keith (Luke Halpin, from Mako: The Jaws of Death and Island of the Lost) and Hobbs (Don Stout), have just finished up the repairs when something very strange happens. Some kind of weather anomaly makes the sky turn funny colors and knocks out both the radio and the compass aboard the little boat. There are some odd disturbances in the water, too. Neither the sailors nor their clients know quite what to make of it all, but it doesn’t seem to threaten the craft and there isn’t a hell of a lot Captain Ben and his men can do about it anyway.

Alarmingly enough, though, the compass still hasn’t righted itself by nightfall, meaning that the boat’s crew will just have to keep sailing a steady course and hope that they’re headed in the right direction. Late that night, Rose goes up on deck to talk to Keith, who is standing the overnight watch. Their chat is interrupted when a large ship, running with its lights off despite the impenetrable darkness, looms up off the port beam and just about runs the smaller craft down. Keith dodges the ship’s prow, but the two vessels sideswipe each other, doing considerable damage to the Bonaventure’s upperworks. As you might imagine, everybody aboard comes racing up to the deck to see just what in the hell is going on. Keith tells Ben about the blacked-out ship, but the captain doesn't believe him. The flare Ben shoots off a moment later shows that Keith was at least half-right, however. There’s a freighter out in the water, alright, but it’s in no condition to have rammed the Bonaventure under its own power. It’s grounded on a coral reef just below the surface of the sea, and from the look of it, the ship has been stranded there for a long, long time. And on the subject of that reef, the Bonaventure happens to be hung up on it too.

Daybreak reveals that the situation is at least a little better than it had appeared the night before, in that the submerged reef is only a few hundred yards from the shore of a small island. On the other hand, it also seems that Captain Ben has disappeared. When the captain doesn’t turn up on or around the boat, Hobbs suggests that he might have gone to the island in search of help. With that in mind, he and Keith begin using the Bonaventure’s tiny dinghy to ferry their passengers ashore. The last trip in turns up something that casts a new light on our heroes’ predicament; Rose looks down at just the right time, and sees the captain’s dead face staring up at her through the glass panel in the dinghy’s bottom! Looks like Ben attempted to swim to shore, but wasn’t strong enough to fight the powerful current that sweeps between the shoreline and the reef. While everyone else is trying to figure out what to do next, Chuck climbs up one of the palm trees to reconnoiter. Off in the distance, about in the center of the island, he sees the roof of some large building poking up above the trees. If there are buildings here, there may be people, and if there are people here, then the castaways have a chance of getting home soon after all.

Those hopes appear to be dashed when the remaining six voyagers reach their destination. The building Chuck saw turns out to be a huge and luxurious hotel, but it also turns out to be a dilapidated ruin, not in much better shape than the wrecked freighter out on the reef. No sooner has Norman begun griping about how they've all wasted their time, however, than the unmistakable sound of classical music reaches their ears from another part of the hotel. Following the sound, the castaways find an old-fashioned Victrola-style turntable playing in a rubble-strewn ballroom. As the record player winds down, an oddly accented voice rings out, demanding to know who the intruders are and what they are doing at the hotel. (The voice belongs to Peter Cushing, who will mostly abandon his efforts to simulate a German accent after this initial utterance.) The unseen owner of voice the begins listening more intently to Keith’s explanation when he mentions the derelict ship that seems to have been the initial cause of their trouble, and sharply asks the young sailor if he was able to make out the vessel’s name. Keith says that he couldn’t, beyond the fact that it began with a “P.” At that, Keith’s interrogator suddenly comes out of hiding (and incidentally, Cushing looks even older and feebler than Carradine), races past his unwanted guests, and runs off toward the beach. You’d think that ship hadn’t been there before, or something.

In point of fact, it hadn’t. And while Keith and the Hotel Hermit are talking, very bad things are happening within its shattered hull. A group of eight men with short, blond hair and ruined skin, wearing heavy, black goggles and what appears to be the uniform of Nazi Germany’s Waffen SS, are getting up from the corners and crevices where they had lain to march along the seabed in the direction of the island. All the old recluse will tell Keith and his companions when he returns to the hotel is that they must all leave the island immediately; he says it would be best if they didn’t know precisely why, but it is urgent that they flee at once— “There is danger in the water.” No shit. The next morning (the condition of the Bonaventure obviously precludes the instantaneous escape recommended by the old man), Hobbs encounters one of the strange men from the ship, and is killed. The culprit and another of his kind are still in the area when Rose, Keith, and Norman find his corpse an hour or so later. Understandably reluctant to tangle with the waterlogged killers, and plausibly reasoning that the Hotel Hermit is somehow connected to them, the three castaways abandon Hobbs’s body and go looking for some answers.

The story the hermit tells them is a bit more than they were prepared to hear. During the waning days of World War II, he says, Nazi Germany responded to the escalating danger of defeat by introducing a new kind of army— the Totenkorps, or “Death Corps.” Through some mysterious combination of twisted science and occult power, the Waffen SS was able to recycle its dead into unstoppable— but also nearly uncontrollable— zombie soldiers. Individual units of the Totenkorps were surgically optimized for service in especially inhospitable environments— the brutal cold of the Eastern Front, or the scorching deserts of North Africa, for instance. The Hotel Hermit, as you’ve probably figured out by now, was an SS officer himself, and he was placed in command of a Totenkorps unit designed to operate underwater. He and his “men” shipped out just weeks before the fall of Berlin, and spent several months prowling the Atlantic, awaiting orders that never came. Eventually even a faithful SS man had to accept that the game was up, and the hermit boarded a lifeboat and scuttled his ship, sending its cargo of amphibious zombies to the bottom along with it. But for whatever reason— that weather anomaly the Bonaventure encountered the other day, perhaps?— the ship has somehow returned to the surface, and as our heroes have already seen, the zombie soldiers are back in business as well.

You’d think a flick about Nazi zombies— aquatic Nazi zombies, no less— would be bombastically overwrought and more than a little stupid, too. And for the most part, such movies are. (Witness Zombie Lake, Oasis of the Zombies, and Joel Reed’s Night of the Zombies [not to be confused with Bruno Mattei’s Night of the Zombies] if you really require proof of this assertion.) But Shock Waves stunningly aims for eeriness and understatement, rather than shock and exploitation, and it hits the mark far more often than it misses. There is quite a bit of real suspense in the second half, and Ken Wiederhorn shows himself to be amazingly self-assured for a novice director. In many respects, Shock Waves can almost be seen as America’s equivalent to Tombs of the Blind Dead. It makes similarly adept use of nightmarish atmosphere and eye-catching scenery to cover for an often illogical script, and like the Blind Dead series, Shock Waves offers a unique and memorable zombie mythos that makes a completely clean break both from Caribbean folklore and from the newer George Romero orthodoxy. Furthermore, though their character design of course differs drastically, the Death Corps resemble the Blind Dead in their uniformity of appearance, their implacably methodical demeanor, and their overall air of inscrutable otherworldliness. In fact, it is to a great extent the actors playing the zombies (and not the respected old geezers at the top of the bill, both of whom were far too expensive to be given much screen-time) who carry the film. And make no mistake, the men under the zombie makeup are actors, not extras. Despite their lack of dialogue or individual character names, these eight men put in riveting performances, particularly in light of the very difficult things they were all asked to do. (You try marching in synchronized formation underwater while wearing an SS uniform, zombie makeup, and opaque black goggles— and making sure never to let any air bubbles escape from your mouth or nose, at that!) The entire cast does an exceptional job all around, but it’s the zombie guys who earn my highest respect.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact