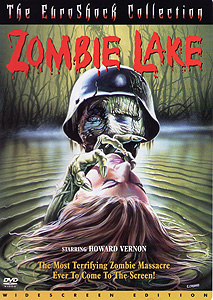

Zombie Lake / Zombies’ Lake / Lake of the Living Dead / Le Lac des Morts Vivants / El Lago de los Muertos Vivientes (1980) -****

Zombie Lake / Zombies’ Lake / Lake of the Living Dead / Le Lac des Morts Vivants / El Lago de los Muertos Vivientes (1980) -****

I am unable to verify this scientifically, of course, but there is strong anecdotal evidence to suggest that Zombie Lake has been reviewed on the internet more frequently than any other European zombie flick. Nearly every member of the B-Masters Cabal has covered it, as have a couple of the Rogue Reviewers and who knows how many websites whose proprietors are not affiliated with any named axis of cinematic evil. No matter who’s writing it up, however, you can just about count on reading a variation on the same anecdote about Zombie Lake’s origins, and I long ago swore to myself that when the time came, I was not going to join the chorus. Now that the time has come, though, I find that I can’t keep that promise; the story seems so utterly impossible that the temptation to retell it is irresistible, and the more I think about, the more convinced I become that any reviewer who fails to mention it has risked denying his or her readers the one clue whereby it might become possible to understand how such a stupendously putrid movie could come to be made. So without further ado…

Once upon a time, there was a Paris-based production company called Eurocine, which specialized in sexploitation horror films. Jesus Franco made a slew of movies for Eurocine during the 70’s, working so cheaply that the company could hardly miss turning a profit on anything he handed in to them. Then, a couple years into the post-Dawn of the Dead European zombie boom, Eurocine producers Marius and Daniel Lesoeur decided to join the big gut-munching party, and commissioned a screen treatment from Julián Esteban, who had previously written Franco’s legendary cannibal catastrophe, Devil Hunter. Something tells me Esteban had just come back from a theater where Shock Waves was playing when he set to work, but we’ll get to that later. Anyway, Franco was the Lesoeurs’ first pick to direct the film, but despite certain familiar Franco trademarks in the completed picture, that isn’t really him hiding behind the pseudonym “J. K. Laser” in the opening credits. No, when the producers told Franco just how miniscule a budget they had in mind for Zombie Lake, the director said to them in essence, “Are you fucking kidding me?! What kind of a hack do you take me for, anyway? I’ve got a reputation to uphold— a fanbase to cater to! I’ll give you a script, but I’m sure as hell not sullying my good name by trying to make a movie on that pittance. You can find some other sucker.” That other sucker turned out to be Jean Rollin, another major luminary on the Mediterranean horror-smut scene, best known for his pioneering lesbian vampire films. Honestly, he was a pretty good choice for a Franco understudy, in that both men have a marked propensity for making movies that seem to have gotten lost on the way to the arthouse, and wandered into the grindhouse instead. With Zombie Lake, however, there would be no mistaking the fact that the film had been designed from the ground up as exploitation trash, and it is no little irony that in the English-speaking world at least, none of Rollin’s more personal work has seen nearly such wide distribution as a film to which he refused to sign his name.

I dare say you wouldn’t have, either. A heartwarming tale of a little girl’s unexpected reunion with her long-missing, blood-drinking, aquatic Nazi zombie father, Zombie Lake is a mind-blowing miscalculation in every imaginable way. The opening scene, in which a twenty-ish girl goes for a nude swim in the lake outside her presumably French village and is set upon by the zombies that inhabit it, sets the tone admirably. The Death of the Skinny Dipper was already a long-established genre commonplace by 1980, but I don’t think I’ve seen it done quite like this anywhere else. To begin with, the underwater shots look more like somebody’s pornographic home videos than they do like anything you’d expect to see in a normal horror movie— in those days before widespread crotch-shaving, you’d have needed a speculum to get a more detailed view than Rollin’s camera shows us when it’s down below the surface. But beyond that, though the setting for the above-water portions of the scene is indeed a tranquil country lake, the rest of it was clearly shot in somebody’s swimming pool, and the shot-to-shot continuity is atrocious. Finally, right before the girl steps into the water, she passes by a sign pointing to the lake, which bears the image of a swimming stick-figure juxtaposed with a skull-and-crossbones. When confronted with this obvious indicator that swimming in the lake is prohibited on the grounds that it is more than likely to result in death, our tanline-free heroine cleverly yanks the sign out of the ground and hides it in the tall grass! So really, she deserves whatever she gets as far as I’m concerned.

A bit after that, one of the zombies climbs out of the lake and wanders into town to kill a young woman who has apparently been doing her laundry in the adjoining stream. This permits us to observe the feeding habits of the undead in some detail, leading to the shocking discovery that they possess the power to open up a live human’s jugular vein without ever breaking the skin. When the dead woman’s father finds her, he leads the rest of the villagers in a procession to the home of the mayor (Howard Vernon, from The Awful Dr. Orlof and A Virgin Among the Living Dead), who seems to understand without having to be told what was responsible for the attack. He sends the body to the nearest city for an autopsy, on the theory that seeing the… um… damage (snicker) for themselves will get the municipal authorities interested in the village’s problem.

No out-of-town cops show up in the immediate aftermath, but a reporter named Katya (Gilda Arancio, of The Intruders, who also played an impressively ineffectual journalist in The Bare-Breasted Countess) does. She arrives at the inn fishing for folktales about the “Lake of Ghosts” (or “Lake of the Damned,” as it will be called throughout the rest of the film), and a man called Chanac (East of Berlin’s Youri Rad) tells her to see the mayor. After a bit of resistance, the mayor agrees to tell Katya the story of how the lake got its name and unsavory reputation. (“In time, folktales can grow into legends… and that is the very stuff of books!”) Back during the war, when the mayor was somehow no younger than he is today, the village was overrun by the Wehrmacht. (You will note that in the flashback that accompanies the mayor’s tale, the German army consists of maybe ten guys who arrive in a single truck, and whose uniforms are almost completely innocent of rank or unit insignia. Their air support, meanwhile, is purely a figment of the soundtrack, and the Resistance forces opposing them are nowhere to be seen, either.) As the assault reached its peak, a young woman inexplicably wandered out into the street, directly into the path of an oncoming Stuka, and one of the German soldiers (Pierre Escourrou) dropped what he was doing to knock her out of the way, taking a bloody but superficial headwound in the process. (Considering the diminutive size of the bomb-blast, I’m amazed he suffered even that serious an injury.) So grateful was the woman that she gave the soldier who saved her a good screwing as soon as he was sufficiently recovered to partake of such things, touching off a romance that not even the worst geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century could thwart. Not that that has anything to do with how the lake acquired its reputation, or anything. Anyway, the local woman got pregnant, but apparently died of complications within a day or two of giving birth; meanwhile, the Resistance chased the Germans out of the village and killed them all in an ambush beside the lake. That lake then became the Nazis’ mass grave, as the mayor prevailed upon the Resistance fighters to dump the bodies in order to protect the village from reprisal. The place has been considered haunted ever since.

Back at the lake, a girls’ sports team trundles up in a customized Volkswagen Microbus. I say “sports team” because even though both subsequent dialogue and the hastily scrawled sign on the side of their vehicle identifies them as a basketball team, the game we see them playing for a few seconds after they pile out of the van is unmistakably volleyball. Hey, Jean? When I, of all people, am able to call you out on a sports-related fuck-up, you’ve definitely committed a boner for the ages. In any case, the girls immediately peel off their clothes and splash out into the lake, where they are killed by the zombies after a few minutes of gross continuity errors (Now the water is waist-deep— now they’re submerged up to their necks with no sign of the bottom anywhere near their feet! Waist deep! Fully submerged! Waist deep! Fully submerged!) and near-gynecological underwater crotch-shots. The last survivor flees into town (still topless, mind you), and passes out on a table at the inn as soon as she’s finished shrieking her fool head off about the lake.

Meanwhile, the zombie who used to be the soldier who fell in love with the village girl has taken to wandering the streets alone in between the mass raids on the populace which the undead begin staging at about this time, and astonishingly enough, on one of those excursions, he meets up with his daughter, Helena (an actress known only as Anouchka, who had appeared in the even sleazier White Cannibal Queen shortly before doing Zombie Lake). Even more astonishingly, Helena recognizes her old man— whom she’s never seen in her entire life— and is not at all put off by the fact that he drinks blood, has bright green skin, and smells like the bottom of a lake. And most astonishing of all, Helena is still only about ten years old, even though she was born nearly four decades ago! It’s a good thing the little tyke’s around, too, because she holds the key to stopping the undead once and for all. You see, shortly after a pair of detectives from the city (one of them played by Rollin himself) finally come in and accomplish nothing except getting themselves killed, the villagers try to take matters into their own hands, and meet with only a little more success (which is to say that they don’t all get eaten when their efforts go awry). In desperation, the mayor then gets in touch with Helena, and persuades her to use her pull with her zombie dad to lead him and the rest of the reanimated Nazis into a trap. Essentially, the girl sets up a zombie soup kitchen in the abandoned mill where she was conceived (“I’ll need a lot of fresh blood,” she tells the mayor, as if that were a request he’s accustomed to fulfilling once or twice every week), and then the townspeople hose the whole place down with the giant, bright-red napalm-thrower one of them just happened to have lying around in his barn.

I can see why Rollin used the pseudonym. Franco was right— it really wasn’t possible to make this movie on the budget Eurocine was offering, and Rollin’s dogged attempt to do it anyway resulted in what is unquestionably the most embarrassing movie of his career. To give you some idea of the true scale of cheapness we’re talking about here, Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs report that the cast had to learn how to act in slow motion at one point, because the camera was running at the wrong speed and there was neither the time nor the money available to have somebody come out to fix the problem! That anyone would try to shoot a film involving an extended flashback to World War II under such tight financial restrictions simply defies belief. No wonder the camera remains stubbornly pointed at the German truck throughout the whole of the “big” battle scene; no wonder the withdrawal of the Wehrmacht was lifted from some other movie; no wonder the vast majority of the background music was recycled from the scores of old Jesus Franco films. (Listen close, and you’ll spot four of the five different arrangements of “Irina’s Theme” used in The Bare-Breasted Countess.) There was obviously no more than a couple of francs available for makeup, either, as the majority of the zombies have merely had their hands and faces painted bright green, and even then it seems that significant compromises were necessary. Note, for example, how many of the zombies wear no makeup on the parts of their necks and forearms which would normally be concealed by cuffs and collars, and keep a sharp eye out for the zombie with the bald spot— the skin of his scalp is a healthy and glistening pink, untouched by the rot that has afflicted his face. One might also question the sense of using water soluble makeup to zombify the extras when the script usually calls for the living dead to be seen swimming in or emerging from a pond! Similarity of subject matter aside, Shock Waves this ain’t.

The thing is, though, that there was at least an excuse for all that stuff. If there was no money, then there was no money; we might say that it would have been smarter not to bother at all than to try to make this movie, in this way, with so few resources, but if that’s what the producers insisted on (and it was), then that’s what Rollin was obligated to try to give them. There are plenty of other fuck-ups in Zombie Lake, however, for which Rollin and company have no alibis. Not noticing that a child who was born shortly after the Allied invasion of Europe would be pushing 40 in 1980, for example— you can’t justify that by pointing to a pocket-change budget! Nor can cost constraints give any kind of absolution to the scene in which Helena’s dead father and his apparent rival for leadership of the zombies get into the slowest knife-fight in recorded history over the appropriateness or lack thereof of an undead Nazi hanging around with his still-human daughter. Most importantly, the whole central conceit of the relationship between Helena and the zombie is so manifestly absurd that nothing in the world could excuse it. And yet neither the scenarist nor the screenwriter seems to have had any trouble finding work in the years to come…

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact