Sword of the Valiant / Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1983/1984) -**

Sword of the Valiant / Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1983/1984) -**

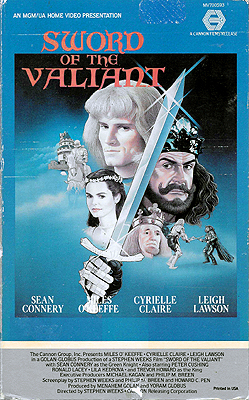

Okay— now it’s time for Cirque du Soleil Wood Elf Sean Connery! I’ve been trying for a while now to find some definitive explanation for why Sword of the Valiant exists, in the particular strange form that it ultimately took, but so far nothing has turned up. Oh, I can understand well enough why the Cannon Group would have wanted in on the sword-and-sorcery action in 1983. That stuff was making money for everyone else at the time, and far be it from Menahem Golan or Yoram Globus to leave any gravy train unridden. I can understand, too, why they’d want an Excalibur ripoff to set alongside Hercules, their sideways bid to cash in on Conan the Barbarian. Golan and Globus were classicists in their way, so it would certainly have appealed to them to be able to offer a throwback of sorts to the Hollywood swashbucklers of the studio era. And if Arthuriana was to be the game, then the tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is as good a source of inspiration as any, and better than most. No, what’s tripping me up here is how the gig ended up going to Stephen Weeks, who’d already filmed that story as Gawain and the Green Knight just ten years before, and how Weeks persuaded the Cannon bosses to let him just make the same movie over again. Because that’s the thing about Sword of the Valiant: despite originating in a poem that not only allows an adaptor to invent pretty much any detailed plot they please, but practically obliges them to do so, this movie tracks Weeks’s previous effort so closely that you almost have to watch both versions back to back in order to spot the differences. And yet for all that re-treading of the same ground in a more experienced and self-assured manner, Sword of the Valiant is no better than Gawain and the Green Knight on the whole, as Weeks somehow manages to make a completely fresh and new set of mistakes.

I’m sorely tempted just to refer you back to my review of the 1973 version for the storyline. Most of the changes really are just that minor. Once again, Christmas finds King Arthur (Trevor Howard, of Craze and The Unholy) in a royal snit over the declining state of Camelot’s knighthood. Once again, a mysterious supernatural being in the form of a green-clad, greenish-skinned, and greenish-haired knight (Sean Connery, of Outland and Zardoz) crashes the holiday festivities to offer the men of the Round Table an outlandish head-chopping bet. And once again, the only one brave enough or foolish enough to accept is a squire called Gawain (Miles O’Keefe, from Ator the Fighting Eagle and Waxwork), whom Arthur knights on the spot so as to make the challenge all nice and legal-like. The Green Knight proves impervious to decapitation, but in light of Gawain’s youth, he agrees to postpone the stipulated return stroke for exactly one year. But in the first noteworthy divergence from the earlier film, the Green Knight offers Gawain a chance to escape from their bargain not by besting him in single combat at some point during the course of that year, but rather by solving a riddle:

| Where life is gladness, emptiness. |

| Where life is darkness, fire. |

| Where life is golden, sorrow. |

| Where life is lost, wisdom. |

Then he climbs back onto his horse, and rides off whence he came.

Weeks and his co-writers fake us out at this point. Yes, Gawain sets out just like last time with equipment borrowed from Arthur himself, accompanied by a single retainer called Humphrey (Leigh Lawson, from Ghost Story and It’s Not the Size that Counts), but their first exploit— a comically unsuccessful attempt to catch and eat a unicorn— is completely original to Sword of the Valiant. And although the ensuing encounter in a magician’s tent is familiar in outline, it’s given a very different flavor by the owner of the tent, who is no mere spell-casting rando, but the arch-witch Morgan le Fay (Emma Sutton, of Lucifer and They’re Outside). For a little while, that is, it looks like Sword of the Valiant will fully exploit the freedom the poem offers to take the quest narrative in a meaningfully different direction from Gawain and the Green Knight. After Gawain and Humphrey cross pathss with Morgan, though, it’s back to the old grind.

Gawain goes to Lyonesse, where he slays the Black Knight (Douglas Wilmer, from The Golden Voyage of Sinbad and The Vampire Lovers), falls in love with the princess Linet (Killer Weekend’s Cyrielle Clair), and nearly gets dragooned into marrying the hag-queen (Blood Tide’s Lila Kedrova) in a loose adaptation of Chretien de Troyes’s 12th-century romance, The Knight with the Lion. His escape from the time-stranded kingdom transports him to a barren wasteland, where he makes the acquaintance of Friar Vosper (Brian Coburn)— who in this version is a thief posing as a man of God, rather than the real thing. Another small difference concerns the sage (Michael Rappaport, of Time Bandits and Tales of the Thousand and One Nights) whom Gawain meets after parting ways with the friar’s band of pilgrims, insofar as this time the character’s help is actually helpful. Indeed, it’s the sage who enables Gawain to approach Lyonesse once more from a different temporal direction, so that he can rescue Linet after all. Mind you, he immediately loses her again, this time to Sir Oswald (Ronald Lacey, curiously reprising his Gawain and the Green Knight role), the creep son of the warmongering Baron Fortinbras (John Rhys-Davies, from The Lost World and Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy). Gawain attempts another rescue, aided deliberately by Friar Vosper (whom he meets again in the dungeon of Castle Fortinbras) and inadvertently by both the baron’s seneschal, Gaspar (Peter Cushing), and his arch-enemy, Sir Bertilak (Bruce Lidington), but enjoys more success in burning down the castle than in springing Linet from it. Finally, as his date with the Green Knight’s axe draws nigh, Gawain is reunited with his oft-distressed damsel at the home of Sir Bertilak, who turns out to have completed the rescue that he himself botched. A knight’s got to do what a knight’s got to do, though, and Gawain forsakes the generous lord’s hospitality to seek out his fate, having solved only three quarters of the Green Knight’s riddle.

Oh, right— the riddle! That was supposed to be important, wasn’t it? The central problem with Gawain and the Green Knight was that the events of the quest never bore any discernable relationship to its ostensible purpose. For all that he was supposedly hunting the Green Knight to force a potentially neck-saving confrontation before the Yuletide deadline, Gawain actually just wandered the land getting into 364 days’ worth of random-ass trouble. The riddle in Sword of the Valiant was supposed to solve that problem, because each station of the quest— Lyonesse, Castle Fortinbras, Castle Bertilak, and the lair of the Green Knight himself— is supposed to provide the key to a line of the verse. That isn’t a bad idea, in and of itself. But to do it really right would have required Weeks to fundamentally rethink what happens to Gawain at each venue. It isn’t enough to bullshit up four lines of nonsense that kinda-sorta captures the vibe of some crap you wrote ten years ago, and then call it a unifying framework. That isn’t how frames work, you know? Besides which, the Green Knight’s riddle functions less as a puzzle to be solved than as a prophecy of Gawain’s future anyway. Indeed, we almost never see Gawain deliberately working to untangle its meaning. Wherever he goes, the questing knight just bulls his way through the peril of the hour, recognizing only in retrospect that the next line in the sequence describes very vaguely what he’s just experienced. The strangest thing of all, though, is that linking the riddle to the random happenstance of Gawain’s quest severs the connection between the supposed organizing principle of the narrative and the nature of the character who sets it in motion. The last time Weeks told this story, the act breaks aligned with the changing of the seasons, and while that initially seemed as meaningless as anything else in the film, it eventually bore fruit when the Green Knight was revealed as a personification of the seasonal cycle. That’s what he turns out to be here, too, but if there’s any parallel between the text of the riddle and the rhythm of the biosphere, I certainly can’t find it.

All that is a prime example of what I mean by saying that Weeks makes fresh, new mistakes in Sword of the Valiant, even as he corrects, at least in theory, the old ones he made back in 1973. There are plenty more, too, where it came from. Gawain and the Green Knight was excessively self-serious; Sword of the Valiant has a bad habit of undercutting itself with jokes that are ill-timed even when they land. Murray Head, Weeks’s previous Gawain, was a drip who could never sell the transformation from callow, impulsive youth to seasoned hero of chivalry. Miles O’Keefe, on the other hand, although markedly better here than he was in Tarzan the Ape Man or the Ator movies, remains not much more than an adequate action beefslab. (To be fair, O’Keefe was forced on Weeks by Golan and Globus, who inexplicably preferred him to the director’s first choice, Mark Hamill. Imagine what a different movie that would have been!) Many of the supporting players are a clear improvement over their 70’s counterparts (Michael Rappaport! John Rhys-Davies! Peter Fucking Cushing!!!!), but the one carryover from the original cast bizarrely results in Sir Oswald being nine years older than his supposed father, and looking every minute of it. This film looks less chintzy than its predecessor with regard to weapons, armor, and costumes, but skimps even more aggressively in other places. O’Keefe’s blond Prince Valiant wig, for example, is just a step up from Tarkan vs. the Vikings, and the workmanlike bombast of Ron Goodman’s old score has been replaced by about eight bars of cheesy synthesizer noodling, which only rarely quite matches the intended mood of the action onscreen.

But to see Weeks run truly hog wild with this “fresh, new mistakes” business, look no further than the Green Knight himself. In Gawain and the Green Knight and Sword of the Valiant alike, the uninvited guest at the Camelot holiday party is far and away the most vivid and memorable character, as is only just. Nigel Green, who played him in 1973, was an awesomely flamboyant, larger-than-life presence, but he was inevitably let down by a costume and makeup design better suited to the stage than to the movie screen. Apart from the green dye in his wild mane of hair and unruly tuft of beard, the only visual indication that he was supposed to be a supernatural being was the vaguely ivy-like appearance of the ruffles on his shirt. This time around, Weeks went much further with the character’s look, but the results far overshoot the uncanny to land in the country of the merely absurd. Connery not only wears green dye in his hair and green foundation on his face, but is covered with glitter— which is green as well. He’s got the leaf motif going once again, but this time it’s a full-body thing, from tiara to greaves. That’s all well and good, but those sprigs of holly at Connery’s temples combine with the green plastic reindeer antlers on his crown to make him look like he’s wearing a Christmas ornament on his head. (Then again, I suppose that would be seasonally appropriate…) And his armor! It’s the kind of thing you see on warrior women in the more crudely libidinal 80’s fantasy art: full plate harness, except that it leaves the whole front of his torso bare from waist to collarbone, revealing that the Green Knight suffers from a serious case of Dutch Elm Dad-Bod. All in all, it’s as if Mike Grell had been entrusted with a profoundly ill-advised redesign of the Keebler Elves.

None of that would have such preposterous impact, though, without Connery’s performance to animate it. I never imagined that I’d one day find myself thinking, “Sean Connery is no Nigel Green,” but in this particular case, he really, really isn’t. This is one of those times when a normally capable actor sinks to the level of crummy material, whereas Green was able to drag Gawain and the Green Knight temporarily up to his own during his few, brief scenes. And because Sword of the Valiant makes significantly more use of the Green Knight than the older film, we get to see Connery do that sinking with some regularity. For years I’ve wondered how it was possible that the only scene in this movie to really stick with me from that span of months when Sword of the Valiant seemed to play on cable TV every three or four days was the Green Knight putting forth his wager. Now that I’ve renewed my acquaintance with the film, however, it seems the most natural thing in the world.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact