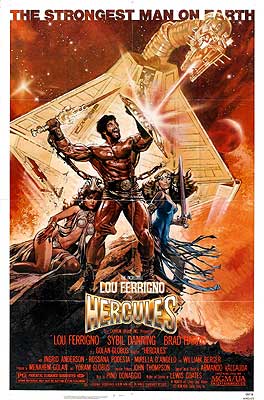

Hercules/Ercole (1983) -***

Hercules/Ercole (1983) -***

Iíll admit, I do tend to rag on Luigi Cozzi an awful lot. For years now, heís been my go-to example of a third-string Italian schlockmeister, a name I drop as a touchstone for the unique combination of the childishly inept, the scurrilously slimy, and the thoroughly bizarre that defined that nationís exploitation cinema in the early-to-mid-80ís. Donít let that mislead you, though. I harbor no grudge against Cozzi. In fact, I mention him so often because heís one of my favorite third-string Italian schlockmeisters, and he deserves to be better known. This is the guy who gave us Starcrash, okay? His writing credits range from Dario Argentoís Four Flies on Gray Velvet to Lamberto Bavaís Devilfish. He even directed a highly regarded movie once, the cult-favorite giallo The Killer Must Kill Again. And yet I have unaccountably never reviewed a single bit of his work. Letís correct that oversight now, shall we? On the surface, Hercules and its sequel, The Adventures of Hercules, were Cozziís attempt to exploit the sword-and-sorcery craze of the early 1980ís. On close examination, however, they also reveal that Starcrash hadnít been enough to work Star Wars out of Cozziís system. While others of his ilk cashed in on heroic fantasy with pedestrian barbarian flicks like Ator the Fighting Eagle, Cozzi offered up a delirious mishmash of retro peplum and Eurocomics sci-fi.

A poor manís psychedelic cosmology opens the film by explaining the origin of the universe and the gods who rule over it. If you happen to have any psilocybin handy, you might want to eat it before watching this sequence; itíll probably look better and make a lot more sense that way. Then, in their headquarters on the moonó not Mount Olympus, as you might have expectedó Zeus (Claudio Casinelli, from Hands of Steel and Flavia the Heretic), Hera (Rossana Podesta, of 7 Dangerous Women and The Virgin of Nuremberg), and Athena (Delia Boccado, from Tentacles and A Black Ribbon for Deborah) ponder the fate of life on Earth now that Pandoraís Jaró not her box, as you might have expectedó has broken open, releasing all the essences, good and evil, that it contained. Athena in particular worries that Evil is too strong not to gain ultimate dominion over the cosmos. On her advice, Zeus crafts a soul of incomparable strength and righteousness out of the purest white light, and dispatches it to Earth to incarnate itself into an invincible champion.

The body that soul picks to inhabit belongs to Hercules, the infant son of King Amphitryon and Queen Alcmene of Thebes. With the impeccable timing that will become a hallmark of its mortal existence, it takes up residence at the very moment when a plot to overthrow the childís parents is springing into action. At the Theban temple of Hera is a sacred sword which supposedly confers mastery over the element of fire upon whomever wields it. A one-eyed archer (Franco Garofalo, from Night of the Zombies and Sex of the Witch) sneaks into the temple under cover of darkness to steal the sword, but heís merely the pawn of a complicated conspiracy. The thiefís employer is Ariadne (Sybil Danning, of Housewives Report and Reform School Girls), daughter of King Minos of Thera (William Berger, from The Spider Labyrinth and 5 Dolls for an August Moon). Minos wants the sword because it will enable him to capture and control the Phoenix, securing immortality for himself and his daughter, and providing Thera with an inexhaustible source of energy. But Ariadne and Minos needed more help than just one burglar, and thatís where Valcheus (Gianni Garko, of Star Odyssey and The Psychic), Amphitryonís captain of the guard, comes in. The theft of the sword presents an opportunity for Valcheus to frame the king for blasphemy, and thereby to open the way for him to seize the throne himself.

Hercules survives the ensuing round of assassinations, however, thanks to the intervention of a loyal chambermaid. She smuggles the baby out to a nearby river and sets him adrift on the currentó although she ends up paying for the rescue with her life. Little Hercules also survives a waterfall thanks to the protection of Zeus, and an attempt on his life by Hera due to his newly acquired preternatural strength. The two serpents the goddess sends against him may look lethal, but Hercules crushes both of them to death with his tiny, bare hands. Then he washes up on the riverbank, where he is found by a childless couple who adopt him as their own.

Twenty years pass, and baby Hercules grows up into Lou Ferrigno (also in Desert Warriors and The Seven Magnificent Gladiators). Whatís that? Yes, as a matter of fact, his maturation does involve pushing a giant grindstone around in circlesó why do you ask? The ladís phenomenal might is obvious both to himself and to his adopted parents, but all three are at a loss to imagine what purpose the gods had in mind when they gave it to him. Hercules vows a quest to find out, however, in the wake of a double tragedy. First, his father (Stelio Candelli, from Nude for Satan and A Man Called Rage) is killed by a bear while the two of them are out in the forest together, uprooting trees for some reason. And then his mother (Gabriella Giorgelli, of Women in Cell Block 7 and The Wax Mask) dies in an attack on the family yurt by a giant robot bug.

Waitó letís back up a bit. You remember King Minos? Daughter stole the sacred sword so that he could imprison the Phoenix, become immortal, and run his kingdom forever on its power? Well, apparently Hera likes the cut of his jib, because sheís enlisted him in her back-channel fight against her husbandís champion. That isnít the kind of mission a smart villain like Minos takes on half-cocked, though, so the king brought in a subcontractor of his own. Travelling into outer space (donít ask me how), Minos besought the aid of Daedalus (Unsaneís Eva Robins), personification of science. (I think sheíd take exception to being called a goddess.) It was Daedalus who created the bug-bot, and she also built Minos two more mechanical monsters which Hercules will have to face before this is all over: a three-headed, cosmic-ray-shooting hydra-bot and a huge, automated centaur which I guess is supposed to be Nessos. In any case, Iím sure you can understand now why Hercules would decide that a quest for divine guidance was in order. Bear attacks can be written off as a lifestyle hazard of making your home in the wilderness, but something is definitely up when giant robot bugs come at you!

Hercules decamps to Tyre, where he has heard that King Augias (Brad Harris, of SS Hell Camp and Goliath Against the Giants, who played Hercules a time or two himself as a young man) is accepting job applications for a quest of his own. His daughter, Cassiopeia (Ingrid Anderson) is due to be married, but her betrothed lives far enough away that it seems like a good idea to give her the most formidable chaperone possible. The hiring process therefore focuses on a series of games meant to test the applicantsí fighting ability, and Hercules aces every stage of the examinationó to the visibly escalating annoyance of Augiasís advisor, Dorcon (Yehuda Efroni, from Sinbad of the Seven Seas and the Phantom of the Opera with Robert Englund in the title role). Eventually, with the conventional means of eliminating an applicant all exhausted, Dorcon proposes a test that only someone truly favored by the gods could pass; in fact, the way he tells it, thatís exactly the point. After all, a man with Herculesís strength could just as easily be a monster in disguise as a hero. Down by the river, there is a stable housing 1000 horses consecrated to Hera. Itís the filthiest, most revolting spot in the kingdom, and if Hercules can clean that stable in a single night, then heís got the job of escorting Cassiopeia to her wedding. If you remember your mythology, you already know what Hercules does. Checking off the boulder-chucking box on the list of mandatory peplum maneuvers, he diverts the course of the river so that it scrubs away all the holy horseshit for him. Cassiopeia is so impressed that she falls inconveniently in love with Hercules. Thatís too much for even Zeus to stomach, however, and he zaps the couple with a thunderbolt before they have a chance to get more than the most tentative start on coupling.

It suits Dorcon just fine to find Hercules laid out beside the princess when he comes for him at sunrise, because the royal advisor is actually working for King Minos. Minos too has his eye on Cassiopeiaó not to marry her, but to sacrifice her to the Phoenix so that it will tolerate its captivity under Theraís volcano for another cycle of death and rebirth. Dorcon was supposed to detour to the Theran capital of Atlantis, disposing of Hercules en route. With the hero already incapacitated, itís trivially easy to toss him overboard into the Mediterranean. Mind you, even that canít stop Hercules for long, but the island where he comes ashore after freeing himself from Dorconís chains is itself a trap of sorts. Its sole inhabitant is the witch Circe (Mirella DíAngelo, from Caligula and Apartment Zero), and no oneó Circe includedó may leave it unless they possess a certain talisman. Circe used to have it, but it was taken from her and hidden by Hera and King Minos to prevent her from interfering with their plans. (What plans were those? Donít you see by now that itís pointless to ask?) Thus begins a rather lengthy detour in which Hercules and Circe must descend into Hell, fight the Hydra-bot, cross the Bifrost, and collect both her talisman and the flying chariot of Prometheus before they can even begin the journey to Thera. And thereís a detour from the detour, too, so that Circe can draft Hercules into fulfilling her promise to the king of Africa (Bobby Rhodes, from Endgame and Hearts & Armour) to irrigate his inhospitably dry country. Then and only then can Hercules throw down with the robot centaur, Ariadne, and King Minos himself in the hope of rescuing Cassiopeia from her date with the Phoenix.

I may hold no grudge against Luigi Cozzi, but for the longest time I did hold one against Hercules. It was those stupid fucking robots. Unless youíve actually seen the things in action, you canít imagine what pieces of shit they are. Crudely designed, cheaply built, and ineptly animated, they make the stop-motion monsters from Jack the Giant Killer look like the ones from Jason and the Argonauts. But even if they had been equal to RoboCopís ED-209 instead, Iíd have objected to them on the grounds that Hercules does not fight Zoids! I think now Iím finally ready to forgive that, though, and to appreciate the Hydra-bot, the Nessos-bot, and the Stymphalian Bug in the same way that I appreciate the Pseudo-Talos in Starcrashó as a dopey but heartfelt fan letter to Ray Harryhausen from someone without one twentieth of his ability.

That doesnít address why Cozzi made the monsters mechanical in the first place, though, does it? The solution to that mystery came to me only once I saw The Adventures of Hercules, and realized that Iíd been watching this movie wrong back in the 80ís, when it enjoyed a brief heyday as premium-cable staple. Despite the timing of their release and the tactics the Cannon Group used to market them, Hercules and its sequel donít really belong in the company of Conan the Barbarian or The Beastmaster. Neither do they belong in the company of such avowed throwbacks as Clash of the Titans and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger. Indeed, the truly appropriate frame of reference for Hercules wonít be found on the theater screen at all. No, to understand where Cozzi was coming from here, we should be looking at comic books from the 60ís and 70ís. Think New Gods; think Jack Kirbyís run on The Mighty Thor; most of all, think Jacques Lob and Georges Pichardís Ulysses. Thatís the intended register for Herculesó larger-than-life heroism, magic technology, and drugged-out mysticism all at the same time. There arenít a lot of movies to fit that bill, either. Cozziís Hercules films and Masters of the Universe were pretty much it until Marvel Studios released Thor in 2009.

Mind you, the Kirbyites and Pichardiens will no doubt come away from Hercules only slightly less disappointed than I did all those years ago. Itís simply a lousy movie, whatever your expectations of it. As tacky, junky, and incompetent as anything to come out of the Great Italian Rip-Off Machine in its final decade of operation, Hercules is all the more impressively unimpressive for the generous funding (at least by Italian standards) allotted to it by producers Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus. The story it tells is pointlessly convoluted, to the extent that it could lose an entire act and still come out better for the cutting. And worst of all, thereís no obvious motivation for most of the action. Look at Hera, for example. In the myths, her antagonism toward Hercules stems from the circumstances of his conception. Stooping even lower than usual, Zeus impregnated Alcmene by impersonating her husband, and Hercules was thus a living symbol of the chief godís compulsive infidelity. Here, though, Zeusís involvement in Herculesís birth is a mere matter of soul-transference, so what in the hell is Heraís beef with the guy? The purpose behind King Minosís villainy is only a little clearer. The care and feeding of the Phoenix at least give him reason enough to want to kidnap Cassiopeia, but what I donít understand is his eagerness to do favors for Hera. Hell, Cozzi goes so far as to call attention to the issue when Minos first goes to meet with Daedalus. He says he doesnít believe in the gods, but sees no reason not to assist them when they ask nicely. What? And letís not lose track, either, of the fact that Herculesís entire career as a hero stems from his motherís death at the hands of one of Daedalusís monsters. So not only is Minosís behavior incoherent, but itís also counterproductive.

Still, as with Starcrash (albeit to a lesser extent), itís hard to stay angry with Hercules. The movie is too much like a tale told by an imaginative nine-year-old for that. Much of the action is so goofy itís delightful, like when Hercules realizes heís too late to save his father, and becomes so furious that he hurls the carcass of the bear that killed him into outer space. (No one will be surprised that the bear-suited dummy used for this sequence is a minor classic of special effects inartistry.) Most of the plot ramblings adhere to the ďbecause itís totally awesomeĒ school of storytelling justification, like the business with the chariot of Prometheus or the journey through the underworld that requires crossing both the river Styx and Norse mythologyís rainbow bridge. The production design shows the same naÔve exuberance that defined the look of Italian sci-fi and fantasy movies in the 60ís, a welcome change of pace in an era of more coherent but also more predictable esthetic bent. And in general, Cozzi takes an infectious childlike pride in his lack of workmanship, akin in kind if not in degree to what I last saw in Tarkan vs. the Vikings. When all is said and done, I feel like I ought to hang Hercules on the door of my refrigerator with a brace of magnets.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact