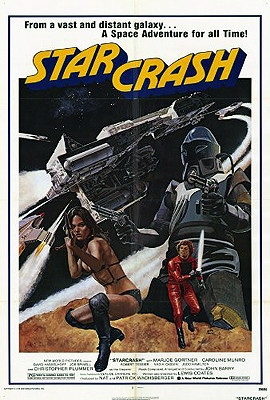

Starcrash (1978/1979) -*****

Starcrash (1978/1979) -*****

Luigi Cozzi claims that when he was hired to co-write and direct a film in the spirit of Star Wars by German producers Nat and Patrick Wachsberger (with overseas buy-in from American International Pictures), he had not actually seen the movie that he was supposed to be ripping off— nor did he go to see it after he got the job. Instead, Cozzi went to his local public library, where he checked out a copy of the novelization. Normally I’m intensely skeptical of stories like that. More often than not, they’re transparent lies concocted to deflect charges of copycatting, like when Steve Miner says he never saw Twitch of the Death Nerve, however obviously he swiped its spear-through-the-bed set piece for Friday the 13th, Part 2. Cozzi’s tale, however, I fully believe. Notice, first of all, that it doesn’t deny Starcrash’s origin as a bid to cash in on Star Wars. But of at least equal importance, Starcrash is exactly the Star Wars cash-in you’d make if your only acquaintance with the source material came from a hackwork translation of a hackwork adaptation into a medium that emphasized all of its weaknesses while completely excising most of its strengths. And when Cozzi goes on to say that he thought of Starcrash as “Sinbad in Outer Space,” well… Caroline Munro, the eye-candy par excellence from The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, is standing right there, and the movie’s several clunky, sword-fighting robots are unmistakably modeled on creatures from other Ray Harryhausen fantasy adventure movies. Cozzi’s counterintuitive approach to the project combines with his inimitable Cozziness to make Starcrash a deliriously strange film. By any sane reckoning, it is undoubtedly the worst Italian (or mostly Italian, anyway) space opera of the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, but in ways that make it also easily the best.

The First Circle of the Universe (wherever that is) is at war with the League of Dark Worlds, ruled by the maniacal Count Zarth Arn (Joe Spinnell, from Vampire and The Undertaker). The count has constructed a super-weapon— not a Death Star, but a Doom Machine— which lies concealed in the interior of a planet somewhere in an ill-omened sector of space called the Haunted Stars. Obviously the Emperor of the First Circle (Christopher Plummer, of Wolf and The Pyx) can’t have that, so he has sent out his son, Crown Prince Simon (David Hasselhoff, from Revenge of the Cheerleaders and Witchery), in command of the mission ship Murray Leinster to sniff out the Doom Machine’s hiding place. The venture doesn’t go well. In orbit around an especially inhospitable world among the Haunted Stars, the Murray Leinster comes under attack by a swarm of giant energy blobs very much like the Diaphanoids from War of the Planets, only red instead of green. It’s difficult to interpret what happens to the stricken starship, beyond that it certainly isn’t good. Three escape craft do manage to get away, but the Leinster herself is never heard from again.

Some time later, interstellar smugglers Stella Star (the aforementioned Caroline Munro, seen also in Slaughter High and The Devil Within Her) and Akton (Marjoe Gortner, of Viva Knievel and Hellhole) are fleeing from the police. It hardly looks like a fair contest. The space criminals’ ship is much too fast to be overtaken by engine power alone, and Stella’s piloting skills enable her to pull off maneuvers that would be suicide for practically anyone else. Still, the trick that shakes off the pursuing units of the Imperial Space Patrol— dropping out of hyperspace in the orbit of a neutron star— is risky even by her mad standards, and she’s forced to ditch the vessel’s massive main power stage in order to escape from the star’s gravity well. That’ll have serious repercussions later, but for now the smugglers’ attention is drawn to a small spacecraft adrift just outside the region of the Haunted Stars. Stella spacewalks over to investigate, and finds a single living crewman aboard. The man is deep in shock, and has obviously been taking very poor care of himself despite the ample stocks of food and water in the craft’s hold. You guessed it— the little vessel is a life-launch from the Murray Leinster, and the two smugglers have just nosed their way into a dauntingly big adventure even for them.

First, though, Stella and Akton have a detour through the First Circle’s correctional system in their future. Thor of the Imperial Space Patrol (Robert Tessier, from The Glory Stompers and The Velvet Vampire) and his robot co-pilot, L (The Last Horror Film’s Judd Hamilton inside the suit, with Hamilton Camp, of Eating Raoul and Evilspeak, providing his English-speaking voice), are one tenacious pair of coppers, and in the time it’s taken the smugglers to rescue the raving-mad survivor of the Murray Leinster, they’ve picked up the trail anew. While discussing what to do with their new passenger, Stella and Akton find themselves surrounded by a whole squadron of Space Patrol interceptors— and without their main power stage, they have no realistic prospect of running away. After a largely off-camera trial, a judge bearing a marked resemblance to the alien ruler in Invaders from Mars sentences the captives to extremely long terms of confinement at hard labor on two different prison planets. (Note that skipping the trial proper leaves us largely in the dark about what Stella and Akton are accused of doing!) Akton gets 200 years on Cetem III (our first hint that the character was originally supposed to be visibly non-human), while Star is condemned to spend the rest of her life feeding a radium furnace on Nocturne II.

As we already have reason to suspect, however, it’s no small matter to keep a woman like Stella Star down. To all appearances, she hasn’t finished serving out the first day of her sentence before she starts plotting escape alongside a man (poliziottescho regular Enrico Chiappafreddo) and his wife (Victoria Zinny, of The Wild, Wild Planet and A Spiral of Mist) who don’t like life in the Nocturne II penal colony any better than she does. None of the three conspirators seem to be thinking about making their break for it right then, but since they conduct their plotting within easy earshot of the guards, I suppose it makes sense that time would not be on their side. Mind you, if Stella and her allies had given themselves a few days to refine the plan, they might have come up with something that wouldn’t blow the entire prison complex to kingdom come, together with all their fellow inmates. Hindsight is 20/20, though, right? In any case, Star makes it perhaps a quarter of a mile from the smoking crater left behind by her handiwork before she gets picked up once again by her old nemeses, Thor and L. But to our astonishment no less than hers, it turns out the space cops were on their way to spring her from Nocturne II themselves— and on orders from no less a personage than the Emperor of the First Circle! Furthermore, the patrolmen’s next stop is Cetem III, where they’re to secure Akton’s release as well. Evidently someone else had better luck getting that space castaway to talk sense, because the Emperor has decided on the basis of his testimony that the galaxy’s most notorious pair of smugglers are the only ones he can trust to locate his missing son. And while they’re at it, maybe they can fulfill Simon’s mission by finding the Doom Machine, too.

At this point— roughly 23 minutes into the film— it becomes absolutely pointless to attempt keeping a detailed, orderly account of the events in Starcrash, because none of them have anything to do with each other. Precious few of them have much to do with Stella’s stated mission, either. There are visits to an ice planet, a beach planet, and a planet of perpetual night. One of those worlds is home to a tribe of Amazons allied to Count Zarth Arn, whose queen (Nadia Cassini, from Emmanuelle’s Silver Tongue and Young, Beautiful… Probably Rich) holds an unexplained grudge against L. Another is inhabited by cavemen (among whom you might spot Sal Baccaro, the Great Italian Ripoff Machine’s answer to Michael Berryman), who mean it literally when they observe that Stella Star looks good enough to eat in those leather bikinis of hers. Thor turns traitor. L repeatedly bounces back from being apparently destroyed. Akton develops a Spock-like habit of revealing previously unmentioned super-powers whenever it’s convenient to the plot. And sword-fighting robots of various sizes keep showing up to remind viewers whose taste isn’t terminally diseased that they’d rather be watching Jason and the Argonauts. Not one bit of it matters in the end, when the Emperor’s forces and Count Zarth Arn’s square off for exactly the same set-piece space battle that they were on track to have anyway.

Starcrash epitomizes pretty much all the reasons why Luigi Cozzi has become my favorite truly terrible Italian filmmaker. Everything about this movie is unrepentantly childish, from narrative sensibility to production design to implicit moral framework, and at no point does it evidence any ambition more sophisticated than to be totally awesome in defiance of the preposterously inadequate talents and resources brought to bear on it. Naturally this comes through most clearly in the look of the film. The spaceship models all have the most incredible “dollar-store John Dykstra” vibe about them, with junk-built hulls conveniently color-coded gold or midnight blue, so that we can see at once who the baddies are. The stop-motion robots are clumsily charming so long as they don’t try to do anything, but reveal all the design faults of their internal armatures with even the slightest movement. Zarth Arn’s mobile space fortress is built in the form of a humongous, clawed hand— which clenches into a fist to indicate battle-readiness! And as if that weren’t enough, the final battle features the Emperor’s forces laying siege to it by pelting it with space torpedoes that each carry a pair of infantrymen instead of a normal warhead. Stella Star’s costumes, meanwhile, could all have been designed by a boy experiencing the first baffling, maddening rush of puberty. Even the starfield backgrounds for the space scenes look like a kid devised them. The individual stars have all the rainbow variability of 1970’s Christmas tree lights, and no effort whatsoever has been expended to make them look like extremely large, extremely distant objects, rather than small ones sited nearby. There’s a certain cracked Eurocomics genius to many of these design choices, which impressed the hell out of me when I saw Starcrash during its brief US theatrical run at the age of five. But of course Cozzi’s effects artists had neither the funding nor the technical ability to render the concepts at all convincingly for anyone not in the habit of pretending that the jungle gym at the playground down the street was the bridge of a starship.

Given what the movie looks like, I don’t suppose anyone should be surprised that the performances and characterizations in Starcrash are straight out of an after-school action cartoon. Caroline Munro is difficult to evaluate as the main heroine, because her voice was dubbed by American C-list character actress Candy Clark. Neither Munro’s physical acting nor Clark’s dialogue readings are bad, exactly, but they’re also never quite in step with each other. It’s an effect I recall vividly from imported anime shows of comparable vintage. Marjoe Gortner’s Akton feels similarly off, but in his case it’s due almost entirely to Gortner’s refusal to wear the alien makeup originally envisioned. Akton’s ever-increasing strangeness (Oh— did we mention that he can expect to live for centuries? Did we mention that he has supernatural healing powers? Did we mention that he can see the future?) would have been less jarring every step of the way if he’d had pointed ears and a lumpy forehead or whatever. Then on the opposite side, we have Joe Spinell setting aside his considerable acting ability in order to chew every cubic inch of the scenery with a paradoxical stiffness worthy of Zarth Arn’s golem robots, while Robert Tessier delivers such a bog-standard evil henchman performance that it would have been more surprising for Thor not to be working for the League of Dark Worlds on the sly. L’s Texas accent is bewildering at first, until you realize that he’s a robot lawman. But the weirdest, most cartoonish performance of all is Christopher Plummer’s as the Emperor of the First Circle. Although Plummer plainly knows he’s slumming here, he makes a good-faith effort to do something with the film’s most conspicuously absurd dialogue and second-tritest characterization. He can’t quite conjure up the authority needed to sell his nonsensical final soliloquy, let alone the command that saves Stella and Simon’s bacon on the Doom Machine planet (“Imperial battleship— HALT THE FLOW OF TIME!!!!”), but it certainly isn’t for lack of trying.

What stands out most about Starcrash’s narrative construction, meanwhile, is that the great majority of it is just stuff happening, to no real or even apparent purpose. I find that more interesting than I probably would if Starcrash were ripping off any other film, because when I reviewed Star Wars back in 2013, one of my readers e-mailed me to say that it was only after reading my synopsis of the plot that she understood how all of its pieces were supposed to fit together. Perhaps Cozzi and co-writer Nat Wachsberger couldn’t follow Star Wars either, and reckoned that a sprawlingly incoherent yet frantically busy story was part of its appeal for the youth audience? In any case, there’s practically no downtime anywhere in Starcrash. It’s virtually nonstop captures and escapes and shootouts and explosions, with a side order each of sword fights, betrayals, and Easter eggs for fans of much older sci-fi and fantasy works. But again there’s almost no connective tissue joining the various set pieces, so that not even the illusion of order or meaning ever emerges. For that matter, even when there is a substantial connection between the events of two different scenes, the scenes in question are as likely as not to come in the wrong order, or to have so many irrelevancies interposed between them that the connection is obscured. A lot of films with more action than sense keep you so breathless chasing after them that their pointlessness becomes evident only in retrospect. Starcrash, on the other hand, is as brazen about its nonsense as Stella Star is about her cleavage.

What you really might not notice until the end of the picture is the profound strangeness of Starcrash’s morality. One normally expects escapist fantasies like this one to rely on an extremely simplistic, black-and-white understanding of good and evil, with spotless heroes and irredeemable villains. Star Wars itself operated mostly within that framework (Han Solo being the obvious exception), at least until the sequels complicated things by retconning Darth Vader’s identity. Starcrash goes a step further, however, in that its black-and-white morality has almost no connection to the characters’ actions. As in the more inept after-school action cartoons of the decade to come, good guys and bad guys alike are simply designated as such, without doing much to earn their way into either category. Count Zarth Arn is evil the way Hordak and Mumm-Ra were evil, his gravelly voice, piercing glare, and maniacal cackle identifying him as the villain with little support from any actions that we see him perform or threaten to perform. The Emperor of the First Circle is good mainly insofar as his kindly and unflappably patient demeanor paint him as a benevolent father-figure to the universe. Certainly Cozzi and Wachsberger made no effort to reconcile the Emperor’s persona with conditions inside the brutal prison colonies run under his authority. And speaking of brutal prison colonies, I’ve already remarked that Stella and Akton are never directly accused of doing anything to warrant their draconian sentences, and that Star makes her escape over the dead bodies of every single sentient being confined on Nocturne II without receiving so much as a stern talking-to in the aftermath! I hasten to emphasize that none of this is portrayed with even a fraction of the care or consideration that would be necessary for it to rise to the level of deliberate ambiguity. This is just one of those films from which the heroes emerge with a higher bystander body count than the villains, and no one says boo about it.

Now if you look again at my opening paragraph, you’ll see American International Pictures credited as this movie’s major overseas investor. You will not find that company’s name anywhere on the film itself, however. AIP boss Samuel Z. Arkoff lost all interest in distributing Starcrash just as soon as he got a look at the finished product— for which I can’t say I blame him, much as I love this travesty of cinema. Arkoff sold the US rights to Starcrash to none other than his former protégé, Roger Corman, so that it emerged here under the imprimatur of New World Pictures instead. The film’s American gross— a little under half a million dollars— might sound like chump change even by 70’s standards, but it made for a tidy profit in comparison to the pittance that Arkoff charged Corman for what he considered an unreleasable picture. That profit convinced Corman that it would be worth New World’s while to start producing modestly-budgeted space operas of its own, which the company continued to do until Star Wars mania had fully run its course. So on top of its own merits (or anti-merits, as the case may be), we have Starcrash to thank for Battle Beyond the Stars and its increasingly wild and weird successors.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact