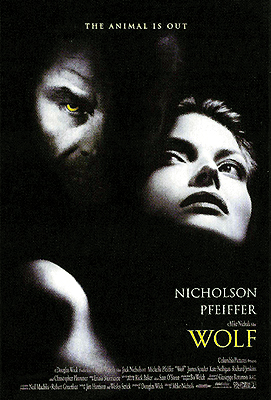

Wolf (1994) ***

Wolf (1994) ***

When the inaptly named Bram Stoker’s Dracula made a healthy profit, it was probably inevitable that both a big-budget, prestige Frankenstein adaptation and a big-budget, prestige werewolf movie would follow soon enough. The connection between Francis Ford Copolla’s Dracula farrago and Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is sufficiently obvious, but only just now do I recognize the accompanying wolf-man picture as part of the set. Wolf is the odd movie out, not only because the script had been kicking around since the last resurgence of interest in cinematic lycanthropy a decade earlier, but because the absence of any 19th-century werewolf novel of widely acknowledged classic stature meant that the producers had little incentive to revisit any specific, oft-filmed tale. Unlike a new Dracula or Frankenstein, a 90’s version of Werewolf of London, The Wolf Man, or The Curse of the Werewolf would have been merely a remake, and a large part of the exercise was to create something at least slightly hoitier and toitier than that. If you look past the contemporary setting and the lack of an antique literary basis, however, Wolf’s place in the pattern becomes obvious. In plot structure, perspective, and even makeup design, it owes more to the wolf-man movies of yore than to the likes of Wolfen or The Howling; its cast is loaded down with big, expensive names; and most importantly, it attempts to build a serious relationship drama out of a premise that would ordinarily pigeonhole it as a horror film, going so far as to refrain from even uttering the word, “werewolf.”

Will Randall (Jack Nicholson) is the editor-in-chief of McLeash House, the fiction imprint of some big New York publishing firm. The parent company has just been bought out by billionaire Raymond Alden (Christopher Plummer, from Starcrash and Dreamscape), and although Alden and the old owners are still hammering out the details of the deal, everybody at McLeash House is concerned about how the changeover is going to affect their jobs. Randall is in an especially precarious position, for he is by no means a young man, and he is widely perceived to be rather cautious and old-fashioned. Speculation is widespread throughout the company that Alden will want somebody younger and more aggressive for the top post. Believe it or not, though, Randall has at least one concern more immediate than his job security just now. On the way home from a contract meeting with an author up in Vermont, he runs his Volvo into what he initially takes to be a large dog. Upon closer inspection, however, the animal seems a little too big and a little too wild to be a dog— frankly, it looks more like a wolf, current geographical ranges be damned. In fact, considering how fast it recovers from being hit by a fairly heavy car, I think even that identification might be a little on the conservative side. And if it is a werewolf Randall has run down, then he’s in an awful lot of trouble, for the creature bites him on the heel of his hand in between coming to and bounding off into the surrounding woods.

Then again, maybe there’s an unappreciated upside to lycanthropy. First, there are the drastically heightened senses of sight, hearing, and smell that Randall experiences during the following 24 hours. No more reading glasses for him! Then there’s the sharp increase in both vigor and virility. Will soon realizes that he feels twenty years younger, and his sex life with his wife, Charlotte (Dracula’s Kate Nelligan), seems poised for a major upturn. But of even greater importance than any of that is the accompanying shift in Will’s personality. Alden does indeed remove Randall as editor-in-chief, appointing as his replacement a rising young kiss-ass named Stewart Swinton (James Spader, of Jack’s Back and Crash). What’s more, a whiff of a suddenly familiar scent on Charlotte’s clothes leads Randall to discover that she has been cheating on him— and with the very same Stewart Swinton, of all people! The old Will Randall would probably have meekly accepted defeat on both fronts, but Wolf-Randall meets the dual affront with fangs and claws bared. He moves out on Charlotte, confronts her and Stewart at the latter’s apartment, and calls Swinton’s smarmy bluff about atoning for the cuckolding with professional self-immolation at the office the next morning. Then he enlists his secretary, Mary (The Devil Within Her’s Eileen Atkins), and his assistant, Roy McAllister (David Hyde Pierce, the voice of Hellboy’s Abe Sapien), in a daring scheme to trap Alden into giving him his old job back. Randall is much beloved by many of McLeash House’s best-selling authors, and he is in a credible position to threaten Alden with mass defection if he isn’t reinstated. Without those profitable writers, McLeash House is worthless to its new owner, and Alden agrees not only to leave Randall in place as editor-in-chief once the final sale documents are signed, but to renegotiate his contract to include a sizeable pay-raise, more autonomy in the day-to-day running of the company, and even the authority to name his successor in the event of his retirement or resignation. With that hard bargain successfully driven, Randall consolidates his position by firing Swinton— in the men’s room, while pissing on the younger man’s shoes. Meanwhile, Will parleys a quick meeting at the Alden mansion dinner party which the tycoon had thrown for the purpose of announcing the fates of the various McLeash House staffers (“Isn’t that a little Roman?” Roy McAllister mused at the time) into an affair with Alden’s rebellious daughter, Laura (Michelle Pfeiffer, from Ladyhawke and What Lies Beneath). All told, it’s a pretty marked turnaround in Randall’s fortunes.

Will is worried, though— worried enough to seek out Indian folklorist Vijay Alezias (Om Puri) to get the closest thing available to the inside scoop on possession by animal spirits. Randall, you see, is sharp enough to make the connection between his personal reinvention and his encounter with the wolf in Vermont, and he’s afraid that there will be a price to pay for his newfound confidence and abilities. Alezias tells Will that the legends he has studied recognize only one explanation for the strange things that have been happening to him of late; Randall is turning into a wolf, and the transformation will complete itself at the next full moon. Naturally, there’s a limit to how far either man actually believes that, but under the circumstances, dismissing the idea out of hand doesn’t seem very smart. Alezias gives Randall an amulet he acquired sometime during the course of his researches into lycanthropy and animal possession, which is supposed to enable the wearer to arrest the final change, or even to drive out the animal spirit if the conditions are right.

It looks like Will is going to need that amulet, too. As the full moon approaches, Randall begins rising in his sleep in a semi-bestial state, and prowling the nearest approximation of wilderness on the hunt. It’s one thing when that means sneaking out of the guest house where Laura lives on the Alden estate, and killing a deer in the billionaire’s nature preserve, but it’s something else again to go around stalking the monkeys at the Central Park Zoo or deliberately courting attack by muggers in the park itself. Worse still, what is Randall to make of it when Detective Sergeant Bridger of the NYPD (Richard Jenkins, of Let Me In and The Core) tracks him down at his hotel room with the news that Charlotte was brutally murdered the night before? Sure, he’s got an alibi, in that he and Laura had spent that night together, but maybe his ever-escalating werewolf powers have made him stealthy enough to sneak out of bed without awakening her. The odd discovery that the tissue samples from Charlotte’s body somehow became contaminated with canine DNA may not mean anything to Bridger, but it sure as hell means something to Will and Laura. But maybe Randall isn’t the only werewolf roaming around Manhattan at the moment. You remember that confrontation I mentioned between him and Stewart Swinton after Will recognized his rival’s scent on Charlotte’s clothes? Well, things got pretty heated between the two men, and Randall became sufficiently pissed off to bite Swinton on the hand.

It’s been a long time since I saw either Bram Stoker’s Dracula or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but Wolf is significantly better than I remember either of those movies being. For that matter, Wolf is at least a little bit better than I remember Wolf being. It had been more than a decade since the world had seen a protagonist-as-monster werewolf film worth mentioning, and Wolf uses to its advantage the principle that everything old eventually becomes new again if you let it sit for long enough. This is not to say that Wolf has nothing legitimately new to say, though, for like its two more conspicuous contemporaries, it gives an uncommonly sympathetic reading not merely to the specific monster at its center, but to the very concept of monstrousness itself. Vijay Alezias states the thesis explicitly when Randall comes to see him for advice: “The demon-wolf is not necessarily evil— only if the man is evil.” But in sharp contrast to Copolla’s take on Dracula, Wolf can get away with such thoroughgoing revisionism because it has no Victorian source-novel to engage, still less one of which it claims to be the most faithful adaptation to date. Note also that Wolf does not shy away from the point that “not evil” is hardly the same thing as “not dangerous,” and that it is far more honest than Bram Stoker’s Dracula in assessing the ramifications of its stance on monsters. Even a “good” werewolf is capable of maiming or killing humans if the circumstances lend themselves to it, as those muggers Randall savages can attest, and it is implied that such occurrences are as inevitable as the occasional human death at the hands (paws, jaws, whatever) of any other large carnivore. For the purposes of this movie, a werewolf is first and foremost a predator just like an ordinary wolf, and in keeping with enlightened modern attitudes about wild predators, Wolf accepts werewolves as a necessary (if perhaps inconvenient) part of the natural order of things. It implicitly places the non-rogue werewolf like Randall outside the categories of human morality when the beast has hold of him; one cannot condemn an animal for acting according to its nature, after all. There is a price for that exemption, however, for in this film’s most interesting departure from conventional werewolf lore, the complete transformation from man to wolf is a one-way affair. The incipient werewolf becomes steadily more bestial until the night of the full moon, after which the animal replaces the man completely. Thus, to live and be judged according to nature’s rules means becoming completely and permanently unfit for human society; it may feel good to be a wolf (to quote Professor Alezias once again), but it is impossible to be a wolf and still be human. The best one can do is seek to control the wolf by means of something like Alezias’s amulet, accepting the risk of driving him away completely and forfeiting forever the power he imparts— and at this point, I’d say the subtext is undergoing its own lycanthropic transformation into just plain text. In any case, the permanence of the change invests the eventual under-the-full-moon showdown between Randall and Swinton with an extra layer of danger. Will can’t fight the partially transformed Stewart without releasing his own inner beast, but if he does, there is little chance of him being able to contain it again, even with the aid of the amulet.

The great irony of Wolf is that the movie in which Jack Nicholson plays a man turning into a wild animal should feature his most restrained performance in ages. It might be taken as a sign of Nicholson’s growth as an actor over the intervening fourteen years that he achieves here what had eluded him in The Shining— his portrayal of the weak-willed “normal” Will Randall really does come across as normal. Perhaps even more surprising, Nicholson doesn’t indicate lycanthropy by just dropping into the all-purpose berserk that often seems to be his default setting, no matter how closely the full moon approaches. To draw again a comparison with The Shining, Nicholson’s werewolf resembles the focused, contained violence of the pursuit through the hedge maze more than the preceding manic rampage around the hotel. That relative subtlety is matched by Rick Baker’s makeup design, too, which looks more like something Jack Pierce would have devised. Randall shows a little more of the wolf each night, but even in the climactic monster duel, we’re talking about pointy ears and unruly sideburns rather than anything you’d expect based on Baker’s An American Werewolf in London work. The most interesting makeup effect in Wolf actually has nothing directly to do with Randall’s nocturnal transformations, however. It’s very inconspicuous, but Randall doesn’t just feel decades younger after the wolf bites him. I’m not sure whether Baker made Nicholson look older than he was at the beginning of the film, or younger than he was later on, but the very fact that I can’t tell which it was is the strongest testimony I can think of to the gimmick’s effectiveness. Considering the marked propensity for excess displayed by both of the upscale monster melodramas that preceded and accompanied Wolf into release, that sort of confident understatement is all the more commendable.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact