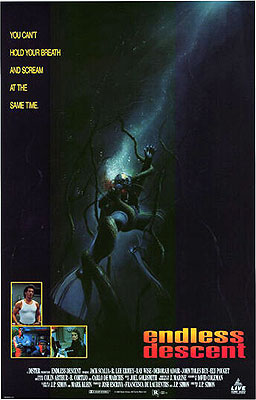

Endless Descent / The Rift / La Grieta (1989/1990) -**½

Endless Descent / The Rift / La Grieta (1989/1990) -**½

It wasn’t just Dino. Practically the entire De Laurentiis family has been involved in the movie business in one way or another— and one needn’t bother stretching the definition far enough to include famous cable TV chef Giada De Laurentiis to make that claim. Grandson Igor and daughters Veronica, Dina, and Carolyna all act. Granddaughter Eloisa does makeup. But most of Dino’s showbiz relations took after the patriarch by becoming producers. Number-two daughter Raffaela is probably the most famous in that capacity, what with Dune, the Conan movies, and the Dragonheart series, but even Federico, the son who died in a plane crash at the age of 26, went down with three production credits already under his belt. In 1989, the inexplicable dawning of the Age of Aquariums provoked two different branches of the De Laurentiis clan to get involved, entering into oblique competition with each other. While Dino’s older brother, Luigi, and the latter’s son, Aurelio, made Leviathan at Cinecitta for MGM, Raffaela’s little sister, Francesca, went to Spain, where she teamed up with director Juan Piquer Simon on Endless Descent. I say the competition was merely oblique because Francesca’s film was a conspicuously cheaper undertaking than Luigi’s, with no hope of more than a token theatrical release in the crucial English-speaking market. Its most direct rival was therefore not Leviathan, but Roger Corman’s Lords of the Deep. But whereas Lords of the Deep was a counterproductively slavish copy of The Abyss, Endless Descent commendably owes very little to any of that year’s better-funded oceanic sci-fi flicks. It’s more an extreme mutation of the old Lost World adventure movie template, with its somewhat fractious submarine crew (not, I hasten to emphasize, the crew of a static undersea base) venturing into unexplored territory, and encountering an entire ecosystem of strange and deadly creatures.

Engineer Wick Hayes (Jack Scalia, of Fear City and Dark Breed) used to work for a company called Contek, for which he designed a remarkable hyper-deep-diving submarine known as Siren. Hayes and Contek came to a parting of the ways, however, when the US Navy dangled merry bushels of cash in front of company CEO Steensland (Edmund Purdom, from Pieces and The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff). Wick, pacifist that he is, refused to countenance the idea of his sub having military applications, and he regarded the design changes demanded by Steensland at the Navy’s behest as tantamount to vandalism. The fight over Siren’s destiny blew up Wick’s marriage, too, because his wife, Nina (Deborah Adair), was herself a naval officer. She not unreasonably took his objections to the militarization of Siren as a judgment upon her profession, which she then generalized into a judgment upon her. Anyway, we meet Hayes on the morning when two Contek goons (James Aubrey, from Demon in My Mind and The Hunger, and Derrick Vopelka) roust him out of bed for an unscheduled meeting with Steensland. It seems that one of the two Siren prototypes has been lost, and everyone involved reckons that Hayes will be needed in person aboard Siren 2 when it sets off on a mission of rescue and/or salvage. Steensland realizes, of course, that Wick’s humanitarian instincts might not extend far enough to cover taking on a life-risking mission for the sake of a former employer whom he’s come to despise, but perhaps things will look a little different if he mentions that the Siren 1 crew included Mark Macy, Hayes’s closest ally and only real friend at Contek. And if even that isn’t enough, there’s also the small matter of Wick’s professional reputation. If it turns out that Siren 1 suffered some kind of structural or mechanical failure due to an inherent fault in the design, then naturally Contek would have to make sure that Hayes took his fair share of the blame, right? When Steensland puts it like that, Hayes sees no alternative but to go along. One look at the Contek boss should be enough, though, to convince you that he’s never told the truth about anything in his life. There’s no telling which part of the specific spiel he gave Hayes is the falsehood, unfortunately, but you can bet Steensland’s lying about something.

The crew that Hayes reluctantly joins is a NATO outfit, drawn from a fair cross-section of the signatory nations. Bafflingly, the filmmakers seem to believe that makes them all civilians, which is… not how NATO works. In any case, Müller the engineer (Frank Braña, from Slugs and Kilma, Queen of the Amazons) is German, pilots Robert Fleming (Tony Isbert, of Inquisition and The Dracula Saga) and Ana Rivera (Ely Pouget, from Death Machine and Lawnmower Man 2: Beyond Cyberspace) are seemingly Dutch and Spanish respectively, Carlo the ship’s doctor (Delirium of Love’s Álvaro Labra) is Italian, dive experts Sven (J. Martinez Bordiu) and Philippe (Emilio Linder, from Forbidden Passion and Monster Dog) are Swedish and French (although neither Sweden nor France are NATO members), and so on. The commander of the mission, however, is both 100% American and 100% military. He’s Captain Randolph Phillips (R. Lee Ermey, of Seven and The Terror Within II), and he visibly hates the idea of plunging deeper into the sea than any human has ever gone before, in an experimental prototype submarine, at the head of a chucklefuck civilian crew, most of whom are foreigners to boot. And he’ll hate it even more once he realizes that his science officer, Lieutenant Nina Crowley, used to be married to the peacenik egghead he’s being forced to babysit just because the guy designed both the aforementioned sub and the one they’re supposed to be looking for. Mind you, if it makes the captain feel any better, neither Hayes nor Crowley are any happier about this whole situation than he is.

Hayes and Phillips first lock horns over the issue of Siren 2’s mission readiness. Wick has been studying the builder’s plans for the sub ever since he signed on, and he’s identified every alteration that was made to the Siren design after he left the project. Having no faith in any of the new systems’ basic compatibility with his own work, Hayes wants the launch delayed until he and Müller have had a chance to go over every inch of the vessel in order to verify that Contek and the Navy haven’t turned it into a deathtrap. Phillips takes that as an impugnment of his service’s competence (which, to be fair, is exactly what it was meant to be), and puts the kibosh on any such undertaking. Inevitably, it will turn out that none of the added or revised systems work worth a fuck, and that they furthermore have a tendency to stop the original systems with which they interface from working. It’ll be far too late to do anything about the defects by the time they arise, of course, and in the meantime, all Hayes accomplishes by standing up to Phillips is to get himself banned from Siren 2’s control room.

Not long after reaching Siren 1’s last reported position, Robbins the navigator (Ray Wise, from Swamp Thing and Dead End) picks up what he believes to be the acoustic homing beacon for the missing sub’s black box on his hydrophones. It appears to be emanating from a rift in an especially rugged patch of seafloor. Siren 2’s shoddy additions so impair the boat’s ability to maneuver in tight spaces that she almost wrecks on the way down, but eventually the rescuers get close enough for Robbins’s sonar to register metal debris consistent with a smashed vessel of approximately Siren-size. The location of the wreckage is very weird, however. What’s left of Siren 1 hangs suspended in a forest of titanic seaweed, despite there being no sunlight at this depth to support photosynthesis. Phillips sends Sven out to reconnoiter, and what the diver finds is stranger still. The weeds are rooted in an even deeper cleft within the main rift, and there’s a readily palpable warm-water current flowing upward from there as well. Sven cuts a sample of the weed for Crowley to study, then proceeds into the debris field— at which point he’s seized and devoured by a huge octopus. Worse yet, Siren 2 itself is attacked soon thereafter by some kind of monstrous invertebrate creature, a bit like a free-swimming sea slug 300 feet long! Things are looking pretty dire until Hayes barges into the control room with exactly the trick needed to send the thing packing (Does it involve reversing the polarity of something that doesn’t seem like it ought to be polarized? Goddamn right, it does!), thereby grudgingly winning his way into the captain’s good graces.

Following the black box beacon into the hole within the hole, the Siren 2 crew eventually find themselves surfacing inside a vast air-pocket cavern, where the remains of a rude base camp testify to the survival of at least a few people after the destruction of Siren 1. Again the beacon calls them still deeper, this time down a winding, narrow passage into the dry part of the cave. Phillips dispatches Hayes to continue the search on foot, together with Fleming, Rivera, Carlo, Philippe, and Joe “Skeets” Kane (John Toles-Bey, from Tales of Erotica and Steel Justice), the one crewmember who might annoy the captain even more than Wick. It’s a good thing they all go heavily armed, because that passage leads into a maze of tunnels infested with organisms that no human (except, presumably, the Siren 1 survivors) ever saw before— and while none of the ceatures are as deadly as that colossal nudibranch, none of them are exactly friends to all children, either. Meanwhile, back aboard Siren 2, Crowley’s weed sample has somehow broken loose from the lab, and is bidding fair to overgrow the entire sub. That’s even worse than it sounds, too, because the plants emit both toxic fumes and infectious spores. Müller succumbs to the former (helped along by the weeds’ acidic sap), and Francisco Grau (Luis Lorenzo, of Hundra and Eliminators) falls victim to the latter. Even that doesn’t exhaust the threats facing the Siren 2 crew, however. Robbins, it turns out, is a Contek industrial spy, planted to make sure that Steensland’s ulterior objective— whatever it may be— takes priority even over the lives of everyone else aboard.

I don’t intend to argue that Endless Descent isn’t imbecilic trash, because it absolutely is. It has all the general not-quite-rightness that you would expect of a film that was written in English, then translated into Italian for the producer, then re-translated into Spanish for the director, and finally re-re-translated back into English for the cast. It also displays the rather different forms of not-quite-rightness that go along with a director sharing no common language with any but a few of the minor performers, and being therefore unable to understand the dialogue recited on-set. For that matter, I suspect there’s even a third layer of not-quite-rightness owing to Endless Descent’s origin as an outer space story hastily reworked for the hot fad setting of the year in which it was made. For instance, the preposterous mischaracterization of NATO as a civilian organization might be minimally explicable in terms of a failed attempt to map the fictional institutions of an imagined future Earth onto some counterpart in the here-and-now, while the bit about reversing the polarity of Siren 2’s radar becomes reasonable enough if in place of “radar” we insert “deflector shields” or some such thing. Still, I don’t think any of the aforementioned handicaps are adequate to explain such foolishness as portraying Captain Phillips to be somehow both a tyrannical ignoramus and a man of honor, or the discordance of cheering for the military during the third act while booing and hissing the military-industrial complex throughout. A smart movie could perhaps make either or both of those contradictions work, but this one certainly can’t. Nor is Endless Descent ever successful at justifying the inevitable reconciliation between Wick and Nina.

All that said, I got more out of Endless Descent in all its trashiness and imbecility than I did from any of the other 1989 sea-strangeness pictures save Leviathan— and this movie can legitimately claim to be more consistent in its entertainment value than that one, since it doesn’t become stupid only during the home stretch to the closing credits. The main reason for Endless Descent’s… well, “success” is the wrong word, but you know what I mean… is its willingness to go its own way, however ridiculous or indeed archaic its own way is. It had been a long time since we’d gotten a proper Lost World film, and I can’t recall ever seeing another Lost World flick that hybridized with the “secret military experiment gone horribly wrong” premise so popular during the late 1980’s. Furthermore, a large part of the movie’s charm is the sheer absurdity of the mechanism whereby the experiment gives rise to the lost world. The conspiracy involved isn’t just ludicrous— it’s fractally ludicrous, fully as ludicrous in every detail as it is in aggregate. At the same time, though, Endless Descent shows an admirable degree of invention in its numerous monsters, and you should all know by now how many points that usually wins from me. I mean, how often do you get to see a submarine-eating sea slug, anyway?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact