The Unholy Three (1930) **½

The Unholy Three (1930) **½

Anybody who thinks Hollywood’s current mania for remakes is unprecedented or even unusual simply isn’t up on their movie history. During the first three and a half decades of the last century, remakes appeared in numbers and with a frequency that seems positively shocking today. During the teens and twenties, it wasn’t unheard-of for a film to be remade two or three times in a single year! And just as it is today, advances in technology were the main driving force of the early 20th-century remake frenzy. A movie that appeared as a one-reeler in 1905 might get remade as a two-reeler in 1910, as a four-reeler in 1915, at full feature length in 1920, with color tinting in 1925, and finally as a talkie in the early 30’s. Once sound came in, the pace of technological advancement slowed down considerably; one might even say cinema technology had reached its first stable plateau of maturity. Otherwise, it’s a safe bet that the frantic remaking would have continued for as long as it took the technical side of the movie business to settle into a comfortable groove for a couple of decades. But even then, you’ll note that each major advance in filmmaking technique brought with it another burst of remake activity: 3-D, Cinemascope, and inexpensive color cinematography in the 1950’s; the stupendous breakthroughs in special effects technology that came between the mid-1970’s and early 1980’s; and now the computer graphics revolution. 1930’s The Unholy Three is an oft-overlooked but important example of the early American remake. This movie, which was the only talking picture Lon Chaney Sr. ever made (Chaney would die of lung and throat cancer before the year was out), had been filmed previously only five years before; the original version was one of the biggest hits of 1925. The remake shows just how literally that term could be taken in the olden days— despite having been helmed by a different director and recycling only two of the original stars, the 1930 The Unholy Three is often all but indistinguishable from its silent predecessor if the sound is turned off.

The focus, once again, is on three sideshow performers— Echo the ventriloquist (Chaney), Tweedledee the midget (Harry Earles, also returning from the ‘25 version), and Hercules the strongman (Ivan Linow)— and a girl named Rosie O’Grady (The Gorilla’s Lila Lee) who picks the pockets of spectators to raise extra cash. Rosie, incidentally, is also Echo’s girlfriend, though the two of them don’t seem to get along very well. The sideshow gig falls apart one afternoon when the short-tempered Tweedledee kicks a child who makes fun of him, touching off a full-scale riot in the show’s main tent. Echo, Hercules, Tweedledee, and Rosie manage to sneak out before the cops arrive on the scene, but the police declare the carnival a public nuisance, and shut it down. That leaves our four protagonists in a two-fold bind. For one thing, they’re all out of a job. For another, sooner or later, the cops are going to find out that Tweedledee started the riot, that Hercules was behind most of the beat-downs that got handed out, that Echo helped the other two men escape, and that Rosie had been emptying everybody’s pockets shortly before the tussle began. Echo, always the brains of the outfit, has come up with a way out of both corners, however. The three showmen will all assume new identities as relatives of Rosie (whose name nobody involved in the riot would have known anyway), and sneak off to go into underhanded business for themselves.

What they do is open a pet shop specializing in birds, with Echo posing as Rosie’s grandmother, Hercules posing as “Granny O’Grady’s” son-in-law, and Tweedledee posing as Rosie’s baby cousin or brother or something. (They rather surprisingly bring along the gorilla from the sideshow when they do it— I don’t know about you, but a caged ape is the last thing I expect to see when I go out parrot-shopping!) And just like last time, it’s all just a front for a burglary ring. Echo sells non-talking birds as talking ones, customers call the shop to complain, Echo and Tweedledee run reconnaissance for robberies while supposedly visiting the owners of the “defective” birds, and the whole gang shows up a few nights later to make off with whatever valuables they found on the premises during their scouting missions. Also just like last time is the means by which the Unholy Three come to grief at the hands of the authorities. Rosie gets a little too friendly for Echo’s comfort with Hector McDonald (Elliot Nugent), the clerk they hired when they set up the phony pet store, and the ventriloquist insists on sticking around to keep an eye on the two of them on a night when he and the boys were supposed to be pulling a jewelry heist. Tweedledee and Hercules get tired of waiting, and head off to do the job themselves, but they end up killing the owner of the house while they’re at it. And because Granny O’Grady is the only stranger anyone can remember having seen the stolen jewels in the week before the robbery, a detective named Regan (Clarence Burton) starts nosing around the store. Echo and his accomplices try to save themselves by framing Hector, but Rosie sees to it that their efforts aren’t nearly as successful as they had hoped.

The odd thing about this version of The Unholy Three is that it somehow seems much more conventional than the original, even though hardly anything about the story has been changed. It’s tempting to chalk that up to the fact that Jack Conway was sitting in the director’s chair once occupied by Tod Browning, but Conway seems to have put a hell of a lot of effort into duplicating his predecessor’s work (even many of the frame setups are close to identical), so I really don’t know if that alone can explain it. Maybe what’s missing is the intangible sense one gets while watching Browning’s version that the project really meant something to him. Or maybe it’s because Conway was more careful to set up some of the crazier twists and turns ahead of time (I’m thinking in particular about that fucking gorilla), so that they don’t seem as jarring as they had in Browning’s interpretation. There’s at least one thing that undeniably is more conventional in Conway’s hands, however— the ape is just a typical gorilla suit this time around, instead of a real chimpanzee on a scaled-down set.

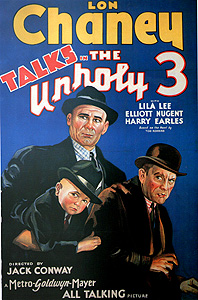

Of course the big deal when The Unholy Three was released was its soundtrack. “Lon Chaney talks!” shouted the one-sheets. But in some respects, I think this may be the film’s greatest weakness. Chaney, for all his famous discomfort with the idea of doing a talkie, comes out well enough, but it was a mistake on the producers’ part to insist that he do his own ventriloquism just as he had picked up so many other odd, specialized skills for previous pictures. For all his talent as an actor, Chaney was a lousy ventriloquist, and since so much of The Unholy Three’s story hinges upon Echo being among the best in the world, his obvious ineptitude is a real problem— one which never even came up in the silent version. Harry Earles also suffers from having to deliver dialogue. Not only does he exhibit an understandable awkwardness acting in English, but the combination of his thick German accent and his childlike vocal pitch makes him almost impossible to understand given the extreme low-fidelity sound recording that was the state of the art in 1930. The necessity of speaking on film doesn’t do any favors for Ivan Linow, either. In fact, just about the only elements of the 1930 The Unholy Three that improve upon its predecessor are the new Rosie (Lila Lee is both prettier and more convincing in the part than Mae Busch had been), and the more believable, more downbeat ending. All in all, it’s certainly interesting to hear Lon Chaney’s voice after all those times I’ve seen him getting by on pantomime alone, but that novelty by itself is not enough to make me prefer this remake of The Unholy Three over the original.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact