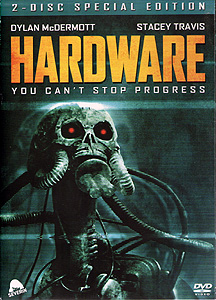

Hardware (1990) ***

Hardware (1990) ***

I kind of love living in a world where movies like Hardware can get double-disc, special edition DVD releases. Chances are you don’t remember Hardware, and if you do, you probably remember it mainly as that post-apocalypse thing where Iggy Pop plays a manic radio DJ and Lemmy Kilmister plays a surly cab-driver. The movie didn’t last very long in theaters, and although its home-video distribution back in the VHS era was initially solid, it quickly became patchy for reasons I’ll go into in a bit. Hardware started life as an extremely modest (as in, budgeted at about £200,000) British production, based on a screenplay by South African-born writer/director Richard Stanley, which exhibited a suspicious, uncredited resemblance to a 2000 A.D. comic strip called “SHOK! Walter’s Robo-Tale.” Specializing in weird documentaries and weirder music videos, the latter primarily for bands associated with the goth and industrial scenes, Stanley had more or less given up on breaking into feature filmmaking by the end of the 1980’s. In fact, when Paul Trijbits and JoAnne Sellar, two independent London cinema owners who had lately expanded into film production, decided that they wanted to bring Stanley’s Hardware script to the screen, he was running around Afghanistan with the Mujaheddin, documenting the waning days of the war against the Soviet Union. Apparently Stanley was reluctant to come back to England, but he did eventually allow himself to be persuaded; the eclectic programming at Trijbits and Sellar’s Scala Cinema had been instrumental in molding Stanley’s directorial sensibilities, and the knowledge that those two were Hardware’s would-be backers was no doubt a factor in his decision. Stanley’s faith in the producers was well-placed, too, for while many in their position might have pulled the plug on Hardware when more detailed and realistic assessments of the project’s budgetary needs pushed the movie’s cost up first to £300,000 and then to half a million, Trijbits and Sellar called for backup instead. Palace Pictures, their company, had ties to Miramax, and £500,000 (or its dollar equivalent) was pocket change for the Weinsteins. American involvement allowed Stanley to spend nearly five times what was originally planned making the film, and access to the Miramax distribution network permitted not only theatrical release, but also a respectable 700-screen opening. By normal Hollywood standards, Hardware was scarcely a runaway hit, but it did well enough in proportion to its trifling cost to become a victim of its own success. The various stakeholders (including the publishers of 2000 A.D.) quickly fell to arguing over who deserved what share of the profits, and Hardware became a difficult movie to see within just a few years. Meanwhile, a much more ambitious sequel, Hardware II: Ground Zero, was smothered in its cradle by the rights disputes. Somebody must finally have agreed to something, though, because Hardware is now back in circulation, in a far more lavish presentation than I ever would have imagined it getting.

The most distinctive thing about Hardware is unquestionably its take on life after the apocalypse. At first, it looks like the usual routine, as a man (Carl McCoy) dressed up very much like one of Death’s minions in Six-String Samurai stalks through the inhospitable dunes of a red-tinged desert beneath a stormy and filthy-looking sky. Eventually, the black-clad nomad comes upon a barbed wire fence enclosing a field littered with metallic junk, and after cutting the wire to let himself in, he digs up the hand and skull-like head of some manner of robot. Irradiated desert setting? Nomadic scavengers? Wreckage of advanced military technology lying around for the taking? Looks like we’re hitting all the traditional beats, right?

The next scene, however, takes us to a bustling if also rather cruddy city. This is a fully functioning population center, with industry, commerce, modern conveniences like electricity and running water— even several TV channels and a somewhat haphazardly run local radio station. In other words, it’s a pretty far cry from Bartertown. Furthermore, this functioning city is part of a functioning nation-state, with a legislature that debates bills, a chief executive who harangues politicians and public alike about the need for this or that policy, diplomatic agencies to engage with the leadership of other states, and a standing military embroiled in a war that we never get to hear too much about. And as we learn once we’ve spent some time in the company of the central characters, this post-apocalyptic society even manages to maintain a manned space program! Again, no details are forthcoming, but the man who calls himself Shades (Alien Hunter’s John Lynch) is an astronaut, and it’s apparently a pretty busy job. His friend, Mo (Dylan McDermott), on the other hand, seems to make his living patrolling the nuked-out desert on whose edge the city stands, supplementing his military wages by selling whatever junk he can salvage out there to a trader named Alvy (Mark Northover, of Willow). Mo and Shades are at Alvy’s place when that nomad from the intro swings by to sell his robot parts, and Mo contrives to buy them before Alvy has even had a look. That’s an odd thing, too, because not only is Mo willing to pay the nomad five times what Alvy gives him for his own latest haul, but he resells only the hand, and is seemingly untroubled about the loss he takes on the deal.

Mo knows what he’s doing, though, whatever it may look like. His girlfriend, Jill (Stacey Travis, from Phantasm II and Dracula Rising), is a sculptor who works mostly in scrap metal, and the robot’s head would be quite a prize for her. Furthermore, Mo knows well that Jill isn’t terribly happy with him just now, nearing the limit of her tolerance for the extended absences dictated by his career. The droid’s head, in other words, is a peace offering as well as a thoughtful gift. It works, too, for although their latest reunion is visibly strained at first, Jill warms up considerably when Mo dumps out the contents of his big sack of salvaged junk. By the time the sun sets, the couple are coupling vigorously— although they’d probably do so in a slightly different spot in the apartment if they knew that they were being spied on from two directions. On the one hand, Jill’s across-the-street neighbor, an amazingly skeezy vendor and installer of home security equipment by the name of Lincoln Wineberg Jr. (Dust Devil’s William Hootkins, who is probably best remembered for his tiny but conspicuous role as the fat X-wing pilot during the climactic attack on the Death Star in Star Wars), has his night-vision telescope set up just right to peek through the girl’s bedroom window, fueling what looks to be turning into an increasingly threatening obsession. And on the other, there’s a bit of life, for lack of a better term, still present within that steel skull from the desert, and the fragmentary machine switches itself back on just in time to get quite an eyeful.

Meanwhile, Alvy has grown curious about the nature and origin of the robot whose hand he bought as part of Mo’s junk consignment that afternoon. Some digging around on what I’d be tempted to call the internet had this movie not been made way back in 1990 reveals the existence of a recently suspended military project called the M.A.R.K. 13. The M.A.R.K. 13 is an artificially intelligent battle droid capable of repairing itself from virtually any form of mechanical or electronic equipment. It has a multitude of retractable limbs outfitted with as many varieties of both ranged and melee weaponry, and its hands and head carry injection syringes for a deadly nerve agent called trifilobim morphate; the drug induces euphoria and hallucinations even as it reduces the victim’s neurons to jelly. The machines were designed to be pretty close to invincible, and they would be were it not for a defect in the insulation that makes them extremely vulnerable to shorting out in the presence of water or even high humidity. That’s why the project was put on hold, as the military isn’t exactly eager to spend a fortune on robot shock troops that can’t handle a little rain. And as you’ve all no doubt surmised by now, there’s every indication that those parts the nomad dug up and sold to Mo came originally from one of the M.A.R.K. 13 prototypes. Alvy calls Mo at Jill’s place, urging him to come out to the shop to discuss the possible financial ramifications of what he’s just learned, and while Mo doesn’t like Alvy’s timing, he does grudgingly leave the apartment after Jill has fallen asleep. That means the pervert across the street will be the closet thing Jill has to an ally when the M.A.R.K. 13 finishes building itself a new body (or the upper half of one, anyway) out of her sculptures and kitchen appliances, and commences the rampage of slaughter for which it was designed.

Hardware is unusual among cheap post-apocalypse movies for the amount of effort and attention that it devotes to world-building. Despite the monster-on-the-loose conflict that dominates the second half, it is a true science fiction film, as opposed to just a horror or action movie with a vaguely developed nuclear war looming over the back-story. In fact, it’s easy to get the feeling that Richard Stanley intended the robot rampage apparently lifted from 2000 A.D. as little more than an enticement to producers, who might have seen it as a cheap and convenient way to ride the last few inches of The Terminator’s coattails. Certainly there’s every sign that the environment he had created interested Stanley far more than Jill’s rather routine travails against the M.A.R.K. 13. The most striking feature of that environment, as I’ve already mentioned, is the markedly incomplete and provisional nature of the world’s “end.” Although it’s plain enough that large sections of the globe were rendered uninhabitable by “the Big One,” modern civilization has survived anyway, at least in places that were of too little strategic importance to be worth nuking directly. This may or may not have been deliberate, but Stanley’s conception of life after a major nuclear war dovetails neatly with the changes in real-world war-planning that went into effect during the 70’s and 80’s. By the middle of the Reagan era, the increasing flexibility, reliability, and precision of nuclear weapons, together with three decades’ worth of mounting political pressure, had led war-planners on both sides of the Iron Curtain to abandon the old city-incinerating paradigm in favor of a primarily counter-force strategy. Advances in delivery systems (the shift from manned bombers bearing single, unguided, multi-megaton H-bombs to ballistic missiles carrying several lower-yield warheads, each with its own independent targeting system, being the most obvious example) had made it fairly clear that the nuclear phase of an all-out war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact was going to be over in a matter of hours if not minutes, and it therefore made very little sense to treat population centers per se as strategic targets; henceforth, destroying government headquarters, military bases, and— to an almost farcical extent— the other side’s nuclear arsenal itself would be the main objective. That would almost necessarily imply a higher short-term survival rate for civilians and non-military infrastructure (the long-term effects of a hemisphere’s worth of fallout would obviously be another matter), and Hardware is the only sci-fi movie I can think of to reflect that new reality in its vision of a post-nuclear future.

That’s important for reasons far beyond giving military nerds like me something to appreciate, too. Maybe this doesn’t apply to anybody else, but I find the question of how people behave when they understand that they’re more or less totally fucked to be an inherently interesting one, especially when they’re more or less totally fucked in a way that does not necessarily preclude or eliminate the need for attempting to carry on some kind of normal life. Mo and Jill are in just such a situation. Their future looks almost unimaginably bleak, but the fact remains that they and the society of which they are a part do have a future. And somehow or other, they have to figure out a way to face that future, even though their options are limited and all of them kind of suck. Just as it did in Mad Max, having all that in the background roots Hardware firmly in reality; the specific forms they take may be different, but the characters in this film face the same fundamental problems that have confronted all humans since the High Neolithic, and that gives this movie a level of credibility that is lacking from DEFCON-4 or Logan’s Run. Furthermore— and this is really the crucial thing— the background material in Hardware stays in the background, informing the story of Mo accidentally giving his girlfriend a homicidal robot as a making-up present without ever overpowering it. This is no Soylent Green, in which the filmmakers go desultorily through the motions of a threadbare A-plot while lavishing all their attention on the setting. Hardware may turn into a by-the-numbers monster movie at the 45-minute mark, but it turns into a competent and often smartly crafted by-the-numbers monster flick— and even then, Stanley makes the setting he’s already established credibly relevant to the battle between Jill and the death-droid. The reemergence of Hardware into the home video market has provoked a certain amount of hyperbole from fans who have been kept waiting far too long for a chance to see it again (or to see it at all in its uncut form). I’m not willing to join the small but vociferous chorus proclaiming it a work of unappreciated genius, but it definitely is a film that deserved far better than it got up ‘til now.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact