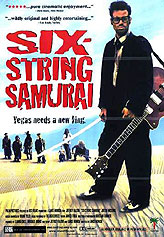

Six-String Samurai (1998) ***

Six-String Samurai (1998) ***

An old joke has it that “homage” is French for “rip-off.” In the same vein, “pastiche” might be French for “ripping off a whole bunch of stuff at once,” and if so, then few movies have ever pastichated more widely and enthusiastically than Six-String Samurai. It’s a chambara epic, a kung fu quest movie, a spaghetti Western, a post-apocalypse adventure. It’s a buddy film, and a road movie, and an alternate history, and a parable of the eclipse of old-fashioned rock and roll by the harsher styles that evolved during the 70’s and 80’s. You can use it for curtains, for pillows, for sheets; you can use it for covers for bicycle seats— and I won’t be a bit surprised if nobody has ever seen writer/director Lance Mungia except as a pair of fuzzy, green arms snaking out from around a corner or behind an obstructive piece of furniture. Fortunately, Death Valley National Park was already a forbidding wasteland when he and his crew got there, so we needn’t feel guilty about the destruction of an ecosystem while enjoying this cinematic thneed.

Six-String Samurai takes as its starting point the notion that nuclear war broke out between the United States and the Soviet Union in 1957. Much of North America was laid to waste, and most of what remained was overrun by the vanguard of the Red Army, but Las Vegas and its environs held out as the last bastion of Truth, Justice, and the American Way. Or sort of, anyway. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison probably wouldn’t have condoned replacing the shattered federal government by crowning Elvis Presley king, but I’m sure it made sense at the time. In any case, King Elvis proved to be a wise and just ruler, and we might also count it as an upside that the demands of governing a nuke-blighted land must surely have precluded Presley from making Clambake in this variant timestream. The ensuing 40 years may have sufficed to transform Las Vegas into a somewhat browner approximation of The Wizard of Oz’s Emerald City, but they could not make King Elvis immortal. Now, as the calamitous 20th century nears its conclusion, the King of America lies dead, and rock-and-rollers from all over the ruined country are making their way to Vegas to compete for the vacant throne.

Among those aspirants is my own personal nominee for the title of Crown Prince Archduke of Rock and Roll, a geeky, bespectacled Texan by the name of Buddy Holly (Jeffrey Falcon, from Caged Beauties and Rape in Public Sea). (And for the record, Elvis was a usurper, if you’re asking me; Chuck Berry was the rightful King of Rock and Roll.) The life of a post-apocalyptic nomad seems to have agreed with Holly, as he hasn’t aged half of the 40 years elapsed since the end of the world. He’s also picked up a curious mastery of both swordsmanship and bare-handed martial arts techniques, with the result that by the time we meet him, he’s basically Minamoto Musashi with a Gretsch hollowbody. A few hundred miles from his destination, Buddy encounters a band of subhuman mutants pursuing a woman (Kim De Angelo) and her child (Justin McGuire) through some of those Amber Waves of Grain we hear so much about. Holly makes short work of the mutants, but not short enough to save the woman. From that point on, the little boy will dog every step of Buddy’s journey like some freak hybrid of the kids from El Topo, Lone Wolf and Cub, and The Road Warrior.

Not long after his first imperfectly successful attempt to shake off his semi-feral young companion, Holly stops in at a wasteland bar where the Red Elvises (the quartet of Russian-immigrant retro-rockers who supplied most of the Six-String Samurai soundtrack) are performing, and where he faces the first true challenge along his road to Vegas. To begin with, the Red Elvises are plotting to kill him for some reason— although they sensibly decide to wait until the proprietor gets him good and drunk before making their move. But beyond that, a doo-wop group called the Pin Pals (Monti Ellison, Kareem, and Paul Szopa, all tricked out in matching bowling outfits) quickly show up and call Buddy out for a… well, I guess you can’t call it a duel when it’s three on one, can you? We may assume that the Pin Pals also covet Elvis’s throne, although one does have to wonder how they anticipate dividing it amongst themselves. We’ll never learn the answer to that question, for it happens that three on one puts the odds decidedly in Holly’s favor; the Red Elvises again postpone their ambush when they see that. In fact, they postpone it so much that Buddy rides off unmolested when the kid catches up to him, now piloting the marginally functional hulk of a ‘52 Plymouth (the would-be king is sharp enough to see that driving to Vegas beats walking, even if it means putting up with a boy who appears capable of communicating only via nonverbal whines), and the band’s real employer is most displeased when he appears at last. Pulling the Red Elvises’ strings is no less a personage than Death himself (Stephane Gauger, done up to look like a cross between The Stand’s Randall Flagg and Slash from Guns ‘n’ Roses), so I’m sure you don’t need me to tell you the price for the underperforming assassins’ dilly-dallying.

Death isn’t stalking Buddy Holly just for shits and giggles. He, too, is bound for Las Vegas with his eye on the vacant throne. Even that is but the means to Death’s true end, however, for once the top-hatted fiend establishes his kingship, he intends to extirpate the rock and roll tradition once embodied by King Elvis, and to rule America in accordance with the principles of heavy metal instead. When Buddy Holly and his fellow claimants face off against Death and his band of irritating minions, it’s not just their lives, but their whole way of life, that’s at stake! As if Holly didn’t already have enough to worry about with three species of mutants, the withered rump of the Red Army, and an assortment of rival rockers standing between him and Las Vegas…

I would have set Six-String Samurai in 1980 rather than 1998, and I’d have had the Pin Pals killed off by a bunch of mop-haired British guys in formerly natty gray suits. Also, since Death is supposed to be the avatar of heavy metal, he really needs to play a B. C. Rich instead of a Stratocaster. Otherwise, it’s amazing how clever and well thought-out a mythology of 50’s-style rock and roll’s decline Six-String Samurai is. My favorite moment in that regard comes during this movie’s take on the spaghetti Western trope in which the hero, glutted on the loss of life that follows him at every turn, attempts to hang up his guns and retire. What leads Buddy to that crisis of the soul is a battle against a young Hispanic guitarist (Pedro Pano, from Demon’s Kiss) who professes to have idolized Holly, and who, under the circumstances of their meeting at last, feels compelled to challenge him to a duel. Buddy does his damnedest to talk the kid out of it, but he won’t stand down, and Buddy is left with no choice but to kill him ignominiously. Again, on the surface, this is pure spaghetti Western. But if, as I suspect, that unnamed Hispanic guitar-player is supposed to be Ritchie Valens, then it’s also a heavily veiled reference to the events of February 3rd, 1959. Valens, with a major hit under his belt and a bright future seemingly ahead of him, spent that winter as the first-set headliner on a tour of the Midwest with Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper, and Dion and the Belmonts. After the February 2nd show in Clear Lake, Iowa, Holly, Valens, and the Big Bopper were killed along with the pilot when their chartered plane to Moorehead, Minnesota, went down in a patch of lousy weather about five miles northwest of Mason City, probably a little after midnight. (The Belmonts, Holly’s backup band, and the road crew were all aboard the chronically malfunctioning tour bus instead.) By all accounts, chartering the plane had been Holly’s idea, so if one were so inclined, it would be possible to see him as having a share of the responsibility for his companions’ deaths. It’s also easy enough to imagine Holly wracked by extra-large survivor’s guilt had he somehow managed to live through the crash himself— just as his mythic counterpart here is moved to turn from his calling after he kills the movie’s probable Valens stand-in. And in a similarly adroit bit of subtle allegory, Six-String Samurai’s simultaneously downbeat and hopeful ending looks a lot like the situation in the early 80’s, when a vibrant rockabilly revival took shape mostly unnoticed in the shadow of hard rock and metal ascendancy.

As important as that stuff is, though, it’s all just subtext, and Six-String Samurai works almost as well without reference to it, as a completely loopy kick-ass action movie. Much like Ryuhei Kitamura’s Versus, Six-String Samurai makes a virtue of bizarre, seemingly indiscriminate derivativeness, throwing together so many things stolen from so many diverse places that it becomes a great deal more than the sum of its secondhand parts. Obviously, the universe of film is so vast at this point that any such claim must be regarded as tentative, but I feel pretty confident in assuming that no other movie has ever copied both Sword of Vengeance and American Graffiti, let alone thrown in The Time Machine, Parents, and The Warriors, too. Six-String Samurai also resembles Kitamura’s work in the sense that it uses techniques derived largely from Japanese samurai epics and Hong Kong martial arts films to reconfigure an oft-used Western premise (post-Road Warrior post-apocalypse here, Evil Dead-inspired zombie-horror in Versus). What’s really shocking is how close this movie— which was made for next to no money over a succession of weekends, as a nearly pure labor of obsession by Americans— comes to capturing the true spirit of Asian action cinema, which was just beginning to attract major notice in the US during the late 1990’s. My working hypothesis is that Jeffrey Falcon deserves most of the credit for that. Six-String Samurai appears to be the only film Falcon completed in this country, but he was a pretty busy man in Hong Kong from the mid-80’s through the early 90’s, playing mostly bit-part villains. It’s a testament to the high standard of physical prowess required in that milieu that the guy Wellson Chin used to hire whenever he needed a gwailo to trade punches with the hero for a few minutes can come over here and look like a prodigy of ass-kicking. Falcon’s acting would be woefully unequal to a lead role in any remotely normal movie, but Six-String Samurai is not remotely normal, and he’s adequate for the film’s purposes during the 90 seconds or so at a time when Buddy isn’t handing out beat-downs to atomic mutants and Russian infantrymen. Of perhaps even greater significance than Falcon’s numerous brief appearances in front of the camera in Hong Kong was his stint as assistant fight choreographer for Dragon vs. Phoenix, an experience which obviously served him well in his capacity as Six-String Samurai’s action director. I’ve seen plenty of movies made on much bigger budgets that fail to match the dynamism of Buddy’s one-on-scads clash with what’s left of the Red Army.

The one thing about Six-String Samurai that I really wish wasn’t there is that damn kid. I get what Lance Mungia was trying to do by including him, and I understand that this story absolutely would not work if the character were removed from it. But it was not necessary that the boy be so god-awful annoying, and it was a big mistake to treat him as if he were the most adorablest little moppet in the whole, wide cosmos when his main functions are to obstruct Buddy’s quest while trying to help, and to give Death and his minions a weakness to exploit. “The boy makes him most uncool,” one member of Death’s backup band observes after seeing the way Holly endangers himself in order to protect the child, and by that point in the movie, it’s hard to disagree. When Buddy tries to palm the kid off on the family of 50’s-sitcom crazies (not realizing that they’re a nest of cannibals), we’re not supposed to greet that development with a sigh of relief, but between the way the boy is written and the way Justin McGuire plays him, any other reaction is asking a lot of the audience. I’m not sure whether it would be better to have him actually be good for something on his own, or to leave him essentially helpless and just dial back on the puling, but either way, the kid needed to suck a lot less for the relationship between him and Buddy to serve its intended function.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact