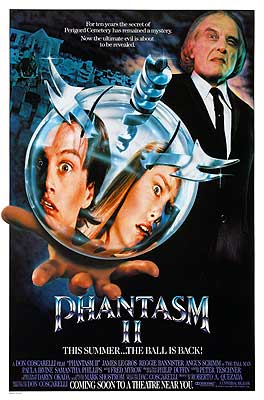

Phantasm II (1988) ***

Phantasm II (1988) ***

Cult success is largely a retrospective phenomenon. Having a cult hit doesn’t do you much good in the moment, when there are costs to recoup and investors to pay back, but give that cult enough time to grow, and it can turn into a real meal ticket eventually. It was Don Coscarelli’s blessing and curse to have two cult hits early in his career: Phantasm and The Beastmaster. The latter film began to pay off earlier, thanks to its notorious run as a staple of early-80’s premium cable, but by the middle of the decade, Phantasm was also attracting some notice on the strength of an extremely well-managed home video release. Indeed, it attracted so much attention that not only did a sequel start looking like a good idea, but it started looking like a good idea to a major studio. When Phantasm II emerged in 1988, easily the most shocking thing about it was the Universal production slate at the very beginning. That major-studio involvement explains some things about Phantasm II. Most obviously, it accounts for the huge improvement, as compared to the first film, in every aspect of production where money matters: special effects, set design and construction, stunts and action choreography, lighting and cinematography, etc. It also accounts for the replacement of Michael Baldwin by a more conventionally handsome actor in the starring role. (Coscarelli was told that he could keep Baldwin or Reggie Bannister, and decided that a fifteen-year-old aging into a different actor was the more believable change.) Most of all, though this is harder to prove, it seems to explain how much less individualistic a horror movie the sequel is than its predecessor. Although Coscarelli’s distinctive and highly personal vision is in here somewhere, it’s difficult to watch Phantasm II without thinking that somebody at Universal wanted a Nightmare on Elm Street 3 or a Hellraiser of their own.

As is so often the case with horror sequels, the first order of business is to undo the previous movie’s conclusion, although here it’s the hero who needs resurrecting. A skillful blend of stock footage and new material establishes that Mike was not irretrievably claimed by the evil, alien undertaker of Morningside Cemetery (a returning Angus Scrimm) and his minions at the end of Phantasm. Rather, he was rescued at the last minute by Reggie (the aforementioned Bannister), who fought his way past the undertaker’s army of bonsai zombies, and blew up his own house with stove gas once he’d hauled the boy to safety in a desperate bid to destroy the otherworldly menace once and for all. Alas, the Tall Man himself had left the premises by that point, so no dice. Or at any rate, that’s the version we get from Liz (Bates Motel’s Paula Irvine), an apparently psychic girl who knows Mike’s story from somehow sharing his dreams. Liz’s familiarity with the back-story matters, because her little hometown of Perigord, Oregon, has become the evil undertaker’s latest base of operations.

Here the movie executes a confusing little time axel, touching down at a moment seven years after the events of Phantasm, but six months before the narration by Liz that frames the foregoing retcon sequence. Mike (now played by James Le Gros, from Solarbabies and *Batteries Not Included) has just been released from the mental hospital where he spent most of those seven years, but he isn’t really “cured.” He’s just grown very adept at telling his doctors what they want to hear. Note that this makes it very difficult to say what really happened before his commitment. Mike may still believe in the Tall Man, but Reggie (who picks him up from the hospital) sticks just as adamantly by the story he was telling the boy before the supposed attack on his house seven years back. There never was an evil undertaker, or a silver sphere, or a goon squad of bonsai zombies, or an interdimensional slave-raiding ring operating out of Morningside Cemetery. And Reggie certainly never blew up his house to save Mike— otherwise, he wouldn’t still be living in it. No, what happened was that Mike went off his nut when his older brother, Jody, died in a car crash mere weeks after the similar deaths of his parents. Okay. But if there’s no Tall Man, then how come the three random graves that Mike digs up at Morningside as soon as he can sneak over there are empty, just as if their supposed occupants had been shrunken and zombiefied? And who the hell is it that now blows up Reggie’s house exactly the way we saw it in the prologue, only with Reggie’s family trapped inside it instead of a pack of monsters? However we resolve the unreliability of the various narrators who got us here, the horrid deaths of Reggie’s loved ones make him a believer. Following an after-hours looting trip to the local hardware store to assemble an arsenal clearly inspired by Ash’s modified chainsaw in Evil Dead II (not to worry, though— Reggie leaves behind enough money to pay for everything they steal), he and Mike head out onto the open road to hunt the undertaker and his creatures across the Pacific Northwest.

Six months of ghost towns and haunted mortuaries later, Mike and Reggie arrive in Perigord, to which they’ve been guided by Mike’s dreams. A little ways outside of town, they stop to pick up a hitchhiker, a local girl named Alchemy (Samantha Philips, from Cheerleader Massacre and Andromeda: The Pleasure Planet) homeward bound after a long cross-country ramble. Mike is a little unsure about the wisdom of that, because dead and undead versions of Alchemy have been appearing in his dreams for weeks, but Reggie argues that if she’s in specific danger from the Tall Man, then she’s better off with them than on her own. There’s practical value in taking the girl on, too, because her father owns a bed and breakfast where she’s sure he’d let Mike and Reggie stay. The boys get their first indication of how deeply the Tall Man has his claws into Perigord when they find that B&B abandoned, along with nearly every other house on the street. Mike, Reggie, and Alchemy set up shop there anyway, and spend the first night fortifying the place.

Meanwhile, Liz is suffering a family tragedy. Her grandfather (Rubin Kushner) has just died, and nobody’s coping very well. Grandma (Ruth C. Engel) is a basket case. Liz’s sister, Jeri (Stacey Travis, of Doctor Hackenstein and Deadly Dreams), flakes out and leaves town right in the middle of the funeral. And there’s no sign of the girls’ parents at all. What’s more, the whole affair is being managed by our old pal, the Tall Man. Some hints of the undertaker’s methodology might be extracted from his relationship with Father Myers (Kenneth Tigar), priest of the church to which Perigord’s cemetery and funeral home are attached. Myers knows what’s going on, but unlike the staff of the funeral parlor (who seem human, but might not be exactly so), he isn’t part of it. Unfortunately, he seems essentially powerless to oppose the Tall Man. The one thing we see Myers do— stabbing Grandpa’s corpse through the heart when he thinks no one’s looking, evidently in the hope of rendering it useless to the undertaker— is only partly successful. Although the damage to the body does seem to make it unsuitable for being bonsaied, the mortuary staff have no trouble bringing it back to life. And even if Grandpa’s no good for slave labor in another dimension or whatever, he can at least bring the undertaker a suitable replacement— Grandma. Liz realizes what must have happened during the night as soon as she awakens to find herself alone in the house, and it’s on her frantic midnight mission to rescue the old lady (Perigord being still sufficiently functional as a town to make digging up graves and breaking into mortuaries a bad idea in broad daylight) that Liz finally meets Mike face to face. The odds are more evenly balanced this time than they were in the original Phantasm. Mike is older and stronger, and he’s well acquainted now with the Tall Man’s tricks. He and Reggie have scads of firepower, and hands-on experience using it in a fight. And while it’s by no means apparent how Mike and Liz might exploit the psychic bond between them, it almost has to be good for something. On the other hand, the undertaker has been building up his strength, too. He has a bigger army of bonsai zombies than ever at Perigord’s funeral home, along with more of the seemingly human servants that Mike calls “gravers,” and not one but three silver spheres— or rather, two silver spheres and a gold one, the latter representing a substantial advance in lethality over the already formidable original model.

The most conspicuous differences between Phantasm and Phantasm II are material. All that Universal money bought things that were far beyond Coscarelli’s means in 1979, resulting in a more polished and professional film. The extra funding gave Coscarelli the freedom to enlarge the scale of the story, elevating the Tall Man from interdimensional grave robber to destroyer of entire communities. It also enabled Coscarelli to pursue more grandiose images of horror, like the overhead shot of a weed-choked but plainly well-used cemetery with every single grave lying open and empty. It made possible the horrendous bodily destruction that the gold sphere inflicts on its victims— which the MPAA ratings board perversely left intact, even as they insisted on the drastic trimming of the silver spheres’ far less grisly full-gallon blood extraction from the R-rated version. (Unrated prints, however, show everything.) Most of all, access to major-studio resources gave Coscarelli the option to build exactly the environment he wanted for the film, instead of just scouting his hometown and its surroundings for good-enough locations. Phantasm’s reliance on the real world of the Pacific Northwest in the late 1970’s condemned it to a drab and smeary visual monotony— a veritable celebration of brown. Phantasm II, in contrast, has both an actual color palette and a definable esthetic sensibility.

The sequel also reflects Coscarelli’s maturation as a writer and a director. It has a much tighter narrative, never getting bogged down in irrelevancies like its predecessor’s fortune-telling sequence or the endless, pointless scene of Jody and Reggie playing guitar together on the latter’s back porch. At the same time, though, this story covers a lot of ground, from reinterpreting what we saw in the first movie— reinterpreting it twice, in point of fact— to introducing a whole new setting, to reinventing its heroes as self-made monster-hunters. All that stuff fits together more or less neatly, not only with itself, but with Phantasm as well, and the one element that doesn’t fit feels like a deliberate mismatch. By leaving open the question of how real the events of Phantasm were, Coscarelli seems to assert that he hasn’t forgotten his previous concern with the malleability of perceived reality under the influence of emotional trauma, even if he’s putting that concern on the back burner for this installment.

And that brings us to the least obvious, but most important change between Phantasm and Phantasm II. You may remember me saying, in my review of the first film, that it was a mystery story at heart. The plot-level emphasis was on uncovering the secret of Morningside Cemetery, while the subtextual emphasis was on the enigma of death itself. Phantasm II’s only pocket of mystery concerns the irreconcilability of its two opening-act retcons, and the resulting possibility that its characters are experiencing multiple layers of overlapping reality— or alternately, the possibility that Mike’s madness is communicable to others who have suffered a loss too big for them to handle. Having raised that question, however, the movie largely ignores it, devoting its energy instead to a more muscular, action-oriented take on the horror genre. No doubt it does so principally because that was the mood of the time. From Aliens to Friday the 13th, Part VII: The New Blood and on, audiences in the late 1980’s wanted to see their monsters battled with main force, not outwitted, outmaneuvered, and escaped. However, kudos are due to Coscarelli for finding a sound in-story reason for the shift. At this point, Mike and Reggie think they know their opponent well enough not merely to fight him, but to make war on him, and what’s more, they’re angry enough over what they’ve already seen and suffered to damn the consequences if it turns out they’re wrong. Phantasm II is thus one of the relatively few really successful ’roided-out sequels to movies that traded in the subtler pleasures of psychology and suspense. I do hope that Phantasm III takes up again the issue of Mike’s reliability as a narrator, though, because the nagging worry that this whole business might be nothing more than a death-haunted teenager’s insane coping mechanism is by far the sharpest weapon in the franchise’s arsenal.

In celebration of getting our home-base website more or less rebuilt after a catastrophic server failure, we B-Masters have hastily slapped together a roundtable devoted to movies about other returns from the dead. Click the banner below to see what else has clambered out of the grave:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact