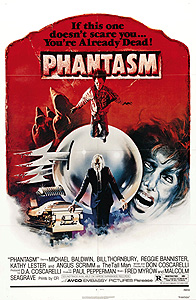

Phantasm/The Never Dead (1979) ***

Phantasm/The Never Dead (1979) ***

Before the term ďhorror movieĒ acquired currency in the early 1930ís, and indeed for a few years after that as well, it was common to see films that we would now so classify described as ďmysteriesĒ instead. Thatís interesting in retrospect, because it is precisely their once-ubiquitous common elements that spookers and whodunits have been most eager to shed in the course of their evolution since those days. Some overlap persists, obviously (although we tend to use ďsuspenseĒ to cover that part of the Venn diagram now), but mysteries for the most part have lost their taste for macabre atmospherics, while horror outside the ghost-story subgenre is no longer much concerned with the solving of puzzles, except insofar as a monster may lack any immediately obvious weakness. Thatís part of what sets Don Coscarelliís Phantasm apart from other contemporary fright films. Phantasm legitimately is a mysteryó a detective story, even!ó despite dealing in subject matter that would normally mark it as a pure horror tale.

Toby (David Arnzen) is an eternal adolescence type from a small town in what I take to be the upper left corner of the United Statesó Washington, Oregon, northern California, maybe even western Idaho or the extreme northwest of Nevada. Like most such guys, he strongly goes in for the simpler pleasures in life, like cheap beer and cheaper women, and at the moment when we meet him, heís just picked up one of the latter after consuming a great deal of the former. Tobyís date (Kathy Lester) is what passes for the adventurous sort out here. Her preferred trysting spot is the Morningside Cemetery, which does indeed offer certain advantages for people looking to get laid al fresco without being arrested for it. Itís dark, itís heavily wooded, the headstones create yet further visual obstruction, and itís not the kind of place people frequent after sundown. The girlís motives for not wanting to be seen are somewhat different from Tobyís, however. No sooner are the poor schmuckís pants around his ankles than she transforms into a dour old man of tremendous height (Angus Scrimm, from Scream Bloody Murder and Mindwarp), and stabs him to death.

Tobyís funeral doesnít draw a big crowd. Apart from family members, itís just his two best friends, Jody (Bill Thornbury, of Summer School Teachers and The Lost Empire) and Reggie (Reggie Bannister, from Survival Quest and Wishmaster). Jodyís little brother, Mike (Mike Baldwin, of Virtual Girl 2: Virtual Vegas and Brutal), would have liked to attend, too, but Jody wouldnít let him. The kidís been really weird about death ever since the accident that killed the brothersí parents, and it seemed to Jody like a bad idea to have Mike in close proximity to another intimately familiar corpse so soon. Unbeknownst to Jody, though, Mike is at Morningside just the same, spying on the proceedings through binoculars from an overlooking hill. He sees a lot more than Tobyís graveside service, too. After the mourners have dispersed, Mike catches the undertaker hoisting the coffin back out of the grave, picking it up all by himself (note that the thing must weigh over 500 pounds between the box itself and the fat guy inside it), and loading it into the back of a hearse. We can see something else as well that isnít apparent to Mike. That undertaker? Heís the same outrageously tall guy who lured Toby to his death by posing as a roadhouse floozy.

Speaking of which, Jody has his own encounter with the undertakerís feminine alter ego a few nights later. Fortunately for him, Mikeó who has been following his brother almost literally everywhere as part of the complex of neuroses that have gripped him since their folks diedó tags along at a discreet distance when she invites Jody to Morningside for a blasphemously illicit fuck. While perving on Jodyís foreplay, Mike is attacked by what might as well be a Jawa; at any rate, itís short and squat but surprisingly fast and powerful, and dressed in a hooded brown robe. In his panic, Mike flees straight toward the grave where Jody is about to get very, very unlucky, unwittingly saving his brother from sharing Tobyís fate. Perhaps understandably, Jody doesnít believe that Mike was jumped by a Jawa when the younger boy explains himself a bit later, but itís plain enough that something scared the shit out of him. Mike, not content with having his story accepted only that far, resolves to sneak into the Morningside Funeral Home the following night to get solid proof that something super-fishy is going on there.

Itís certainly one hell of an adventure the kid has. To begin with, the funeral parlor and its grounds are absolutely crawling with those hooded dwarves, and theyíre not at all happy to see Mike. Neither is the caretaker (Kenneth V. Jones), who seems human at least, but goes about his job with far greater lethality than would normally be considered appropriate. Even more lethal is the sliver sphere, a sort of mechanical watchdog that patrols the buildingís interior after hours. A bit bigger than a manís fist, the silver sphere flies through the air with no visible means of propulsion. When it detects an intruder, it extends a pair of forked blades, and hurls itself at the targetís head. Once those blades have anchored it in flesh and bone, the sphere deploys a drill-like siphon through which it extracts all of the victimís blood, ejecting it in a fountain through a portal on the opposite side. The device apparently has only the most rudimentary intelligence, however, because it has no compunctions about killing the caretaker instead when Mike dodges its attack. Of course, the greatest danger at Morningside is the undertaker himself, but he inadvertently ends up providing Mike with the unanswerable evidence he sought. In his final struggle to escape, Mike is forced to sever a bunch of the inhuman manís fingers, and he has the presence of mind to take one with him as he flees. Normal peopleís digits donít bleed yellow, nor do they remain alive and motile after you cut them off.

Ohó and normal peopleís digits also donít turn into shaggy little monsters once theyíve sat around for an hour or two. Mike and Jody are busy dealing with the fact that the undertakerís fingers do when Reggie drops by for a visit. Naturally, Reggie is curious as to why his friends are feeding a shaggy little monster into the garbage disposal, so he gets filled in on the secret of Morningside, too. Or at any rate, he gets filled in that there is a secret. Jody and Mike canít very well fill him in on the secret proper, since they donít really know it themselves as yet. A second reconnaissance missionó this one undertaken by Jodyó turns up some information about the nature of the hooded dwarves when one of them accidentally kills itself in a car chase with the older boy. When Jody pulls the creatureís cowl away from its face, he finds Toby looking lifelessly back at him! The way the lads figure it once theyíve had a chance to talk the situation over, the undertaker must be transforming the dead of their little town into bonsai zombies to create some kind of army or slave labor force. Who knows how long itís been going on, or how many of the graves at Morningside are secretly empty? Hell, as Mike is quick to point out, the undertaker might even have subjected his and Jodyís parents to his infernal resurrection process. That settles it. Itís time for one more visit to the funeral parloró only this time, itíll be Mike, Jody, and Reggie all together, and theyíll be going in armed. Theyíre going to get to the bottom of the Morningside weirdness, and then theyíre going to put a stop to it!

Phantasm exists because Ray Bradbury had already sold Disney the film rights to Something Wicked This Way Comes when Don Coscarelli came around looking to buy them for his own use. When you realize that, this movie no longer seems so much to have come out of absolutely nowhere. Like the Bradbury novel, Phantasm is a parable of a boyís fear of mortality and loss. Its key setting is a mildly exotic placeó that is, a place that figures at one time or another in just about everybodyís life, but only on narrowly circumscribed terms, under circumstances outside the routine of daily lifeó where the staff are engaged in nefarious supernatural business under the noses of an entire community. It even includes the specific, unsettling detail of victims being transformed into dwarf-like servants of the primary villain. And both stories posit the family bond as something uniquely powerful against the forces of evil, which in turn puts the breaking of that bond among evilís special preoccupations. That said, Phantasm is nothing as easy or obvious as I Canít Believe Itís Not Something Wicked This Way Comes. Even the most sinister carnival must exert some attraction to function as a business. Funeral parlors, on the other hand, are places of sorrowful necessity; nobody ever goes to one in search of pleasure or excitement. (Well, okay. There was that one time at Ahlgrim Family Funeral Services in Palatineó but they have a mini-golf course and a game room in the basement!) Angus Scrimmís undertaker, similarly, is no Mephistophelian seducer like G. M. Dark. He is a figure of unalloyed horror and revulsion except in his female guise, and even then the only temptation he offers is crudely sexualó physical bait for a physical trap, in contrast to Mr. Darkís invitations to open-eyed soul-selling. And because this is a film from the 70ís, Phantasm is inevitably more pessimistic than Something Wicked This Way Comes about the outcome when familial love comes up against interdimensional grave-robbing conspiracies.

Then thereís Phantasmís most famous feature, which has no connection to the Bradbury novel at all, nor to any other media source. The nightmarish image of the silver sphere is exactly that, something from Coscarelliís own nightmares. Considering how firmly the otherworldly device sticks in the mind of everybody who watches this movie, and its prominent place in Phantasmís marketing campaign, itís rather a shock to see how small a role it actually plays. The sphere appears just twice, and only for a few moments on each occasion. Thatís actually an extremely smart move on Coscarelliís part, though. It emphasizes the lethality of the sphere, its speed and precision of attack; either you neutralize the machine quickly, or you die.

Coscarelliís most impressive achievement in Phantasm, though, is the filmís pervasive sense of reality in total collapse. Phantasm is comparable in that respect to The Gates of Hell or even The Beyond. The sheer weirdness of the unnatural goings on has a lot to do with that, certainly, since it pushes us into genuinely unfamiliar territory. Not only are Mike, Jody, and Reggie dealing with something outside of ordinary human experience, but itís obvious nearly from the outset that whatís happening at Morningside is also beyond commonplace bogeymen like vampires, mad scientists, or Satanic cults. Indeed, even at the end of the film, disconcertingly large gaps remain in the protagonistsí (and our) understanding of the undertaker and his operations on this plane. The unmooring of reality is so effective as to redeem an ending that should be doubly infuriating, relying as it does upon two horror movie clichťs that Iím thoroughly sick of seeing.

Unfortunately, Phantasmís substantial virtues are counterbalanced by several of the flaws one generally sees in the work of inexperienced young filmmakers like Coscarelli was at the time. The pacing is lumpy and the action repetitive, working against Coscarelliís otherwise admirable efforts to create escalating tension. In particular, a garishly nonessential scene of Jody and Reggie playing guitar together on the front porch of the formerís house gobbles up several minutes to absolutely no purpose beyond drawing out the running time. Thereís also a plot cul-de-sac early on, in which Mike visits a mute psychic (Mary Ellen Shaw) and her interpreter daughter (Terrie Kalbus) for guidance after discovering the undertakerís superhuman strength. Not only does the psychicís advice have little bearing on anything that happens later, but the consultation is lifted wholesale from the scene in Dune where Paul Atreides is tested for courage by the Reverend Mother Mohiam. You know the one: ďI must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little death that brings total obliterationĒ and so forth. A fanboy shout-out is one thing; an intact and unassimilated chunk of somebody elseís story bulging like a tumor from the tissues of yours is something else altogether. And while weíre talking about Mike, heís a peculiarly incoherent character, as if his age had fluctuated between drafts of the script, and not enough effort were put into reconciling scenes written for twelve-, fifteen-, and seventeen-year-old versions of him. Acting, meanwhile, is strictly at the community theater level, with Angus Scrimm alone showing much ability or potential for future development. All in all, Phantasm is a movie that I appreciate more for its aspirations than for its accomplishments. Itís an ambitious film that overreaches its creatorsí abilities, and itís easy to see why Coscarelli would return to this premise three times over the ensuing twenty years.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact