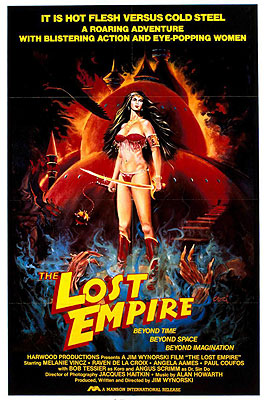

The Lost Empire (1983/1984) -**½

The Lost Empire (1983/1984) -**½

Jim Wynorski’s directorial debut wasn’t quite a Springtime for Hitler situation, but it wasn’t far short of that, either. The funding for The Lost Empire came not from Roger Corman, for whom Wynorski had been working since 1980, cutting trailers, devising ad campaigns, and writing the occasional screenplay, but rather from a theater owner of Wynorski’s acquaintance by the name of Henry Plitt. Plitt was a pretty big player on the exhibition side of the movie business; his Plitt Theatres company controlled what had been Paramount’s theater chain before the Federal Trade Commission lawsuit that forced the studios out of the exhibition game in 1948. In the 80’s, though, American antitrust law was a farcical shadow of its former self, so there was nothing, practically speaking, to stop an exhibitor from getting into production. And since Plitt was looking to park a bunch of money in some project that he could write off as a loss on his 1983 tax returns (before presumably recouping the investment in some future tax year), financing a low-budget indie film was an attractive prospect. Wynorski, for his part, didn’t realize until the picture was in the can that he’d been hired as a tax shelter, so he approached the project in total earnest— or at any rate, in what a New World Pictures alumnus of the early 80’s would understand as total earnest. That’s easily the most surprising detail of the story, because if any movie has “sure, I’ll help you hide a few hundred grand from the IRS” written all over it, it’s The Lost Empire. Part vanity project for the director’s girlfriend, part multi-layered inside joke, and part love letter to Russ Meyer, The Lost Empire looks like it was produced completely without reference to the entertainment preferences of any commercial audience that had yet been widely recognized in its day. But it’s also a surprising amount of loopy fun, and if you’re the sort of person who likes nothing better than watching big-titty girls shoot, stab, punch, and otherwise put a hurting on goons of various persuasions, you’re likely to be in absolute heaven for the bulk of its running time. Even Plitt saw the appeal as soon as he’d had a chance to screen the film, and perceived at once that he really was going to have to sit on it for a while in order to maintain the fiction that he’d lost money on the deal.

An opening crawl informs us that untold thousands of years ago, a brutish and primitive humanity was ruled over by the culturally advanced and magically adept pre-human civilization of Lemuria, but that these prehistoric super-beings exterminated themselves in a cataclysmic civil war. No proper record of the Lemurian apocalypse has survived the intervening ages, and the only traces of it to be found today are hidden in mankind’s most ancient legends. (Wynorski doesn’t specify which legends, but my mind goes immediately to the Titanomachy, the Aesir-Vanir conflict, and the wars between the Tuatha De Danann and the Fomorians.) There is, however, one concrete holdover from the heyday of Lemuria, a pair of mystical gemstones called the Eyes of Avatar. The jewels were separated at some point, and subsequently lost altogether, but it is said that whoever brings them together again will have the power to rule the world as absolutely as the Lemurian sorcerer-kings once did.

We’ll all have some idea what it means, then, when we notice that the single, ruby-like eye of an ill-maintained statute sitting neglected among the more desirable merchandise in a Chinatown jewelry importer’s shop has a curiously purposeful glow about it. Obviously the three ninjas who drop in just after closing time know what it means, too, because they all gang up to pry at the stone eye as soon as they’ve finished killing the shopkeeper. Not one of them has brought the proper tools for such work, however, and they’ve made no progress by the time the police arrive on the scene in response to the store’s burglar alarm. The ensuing pistols-vs.-shuriken shootout leaves only Patrolman Rob Wolfe (Bill Thornbury, of Summer School Teachers and Phantasm) alive, and even he looks unlikely to last too much longer.

It happens that Rob’s big sister, Angel (Melanie Vincz), is a cop herself— and if we may judge by her introductory scene, in which she blows away a whole pack of creeps taking hostages at an elementary school, she’s a rare female specimen of the Cop on the Edge. Angel’s exploits at the school severely embarrass her arch-rival on the force, a man named Prager (Blackie Dammett, from Nine Deaths of the Ninja and Class Reunion) who confusingly seems to be both a uniformed officer and a plainclothes detective depending on the needs of the moment, in front of both their captain (Kenneth Tobey, of Strange Invaders and Body Shot) and FBI agent Rick Stanton (Paul Coufos, from Chopping Mall and 976-EVIL II). Prager reacts badly enough in the moment, but his offstage behavior later on must be even worse, because the next time we see him, he’s getting booted out of the department altogether. (He’ll be back again later, with an upgrade from Backstabbing Nogoodnik to Surprise Villain Henchman.) In the meantime, we learn that Angel and Rick are a couple, and Angel learns that her brother was gravely wounded in Chinatown last night. (By the way, if you look closely, you’ll see that the ninja attack on the jewelry store can only have occurred after the hostage situation at the school, even though the two incidents are presented in the opposite order. It’s an extremely strange editing choice.) She and Rick rush to the hospital, arriving just in time to catch Rob’s unhelpfully enigmatic final words: “The devil is real. The stones know.” He also hands over a piece of physical evidence with his dying breath, one of the throwing stars which the ninjas used on him and his fellow officers.

Stanton, fortuitously, has seen something like that before. Evidently it’s the signature weapon of the assassins employed by an international crime lord known as Lee Chuck. Chuck is an interesting guy if even a tenth of what people say about him is true. Supposedly Satan granted him immortality 200 years ago in exchange for the harvesting of one human soul each day in perpetuity, and rumor places him at the scene of every major disaster to have occurred in the world since then. Rick doesn’t seem to believe that exactly; rather, his theory appears to be that a dynasty of Tong bosses or some such thing has been cultivating the legend of Lee Chuck throughout the past two centuries in order to build up a mystique around themselves. If those ninjas at the jewelry store were using these shuriken, then obviously Lee Chuck— or whoever is currently using that name— is up to something in town. That happens to dovetail in an interesting way with the case that Stanton was already working in partnership with another agent by the name of Charles Chang (the conspicuously non-Chinese Art Hern, from Simon, King of the Witches and Transylvania Twist). A cult leader known as Dr. Sin Do (Angus Scrimm, of Sweet Kill and Vampirella) has been recruiting women for a series of bloodsport tournaments at his villa on his private island in the western Pacific, and not one of the contestants has ever been seen again. Chang believes that the reason for the disappearances is not that the competitors are all being killed in the fighting, sold into slavery, or some other such thing, but rather that Sin Do is secretly training and brainwashing them to create an elite all-female terrorist army. And it just so happens that Dr. Sin Do is reputed to have ties of some kind to Lee Chuck.

Wolfe has a really bad idea when Stanton and Chang explain all that to her over drinks at the Golden Pagoda: what if she signed up for the next round of Sin Do’s tournament? Rick tries to dissuade her by pointing out that the cult leader accepts applicants only in groups of three as some kind of cockamamie security measure, but that actually suits Angel even better. With two other women by her side, she’ll be able to bring along her own backup. Angel knows just what backup she wants, too— drawn, somewhat ironically, from acquaintances on both sides of the law. On the one hand, there’s Whitestar (Raven Delacroix, of Up! and Frankenstein vs. the Creature from Blood Cove, whom Wynorski incredibly managed to be dating at the time), the two-fisted Indian shamaness whose tribe Wolfe helped out of a serious jam some years ago. And on the other, there’s Heather McClure (Angela Aames, from H.O.T.S. and Fairy Tales), whom Angel once busted for a crime that rather defies classification. McClure somehow seized control of the tower crane at a construction site during an epic piss-up, and used it to drop an entire other building on Wolfe’s police station! You can see how that combination of moxie and outside-the-box thinking might come in handy on a mission to infiltrate a cult leader’s offshore terrorist training camp.

Wolfe, Whitestar, and McClure quickly discover that a gathering all-girl terror army is the least of the bad news percolating on Dr. Sin Do’s island. For starters, the connection between Sin Do and Lee Chuck is an extremely simple one: they’re the same guy. Also, that story about the Devil granting Lee Chuck immortality in exchange for a steady supply of stolen souls? It’s true. And although this won’t mean anything to the three infiltrators, on account of they haven’t seen their own movie’s opening crawl, the nefarious mystic has clearly been at it a lot longer than 200 years, because he’s the last of the Lemurians. Lee Chuck’s true objective is to get his hands on the Eyes of Avatar in order to power some manner of superweapon, and one of them is already in his possession.

But as bad as all that is, the worst is yet to come. You see, the Eyes of Avatar aren’t just a couple of sparkly rocks. The ancient magic infused into them has given them a form of life, and what’s more, a form of intelligence. The Eyes want to be found, and they want to be reunited in Lemurian hands. Angel didn’t notice this, but when she went to look over the jewelry shop where Rob received his mortal wound on the evening following his death, the Eye of Avatar sought by Lee Chuck’s ninjas teleported itself out of its setting in that old statue’s eye socket, and into the bottom of her purse. Back home in the states, Stanton had already half-convinced himself that he needed to sneak his way onto Sin Do’s island to rescue Angel from… well, surely something, right? And the next time Rick comes round to make sure that all’s well at his girlfriend’s apartment, the Eye of Avatar hiding in Angel’s purse hypnotically persuades him not only that he really should do it, but also that he should bring the stone with him when he goes. Stanton gets captured immediately upon making landfall, doing Wolfe and her companions no good at all and giving Lee Chuck the thing he’s wanted most for who knows how many centuries. It’s just a good thing for everyone that the latest crop of commando girls haven’t yet received their full indoctrination, and that even Sin Do’s fully processed soldier babes are significantly less loyal than the Lemurian wizard imagines.

There’s a case to be made that The Lost Empire is Jim Wynorski’s Andy Sidaris movie (although it slightly predates all the films that Sidaris is mainly known for), and thinking of it in those terms helps bring into focus what makes it so much more enjoyable than anything the latter director has done except for maybe Hard Ticket to Hawaii. For one thing, Wynorski, even at the very beginning of his directorial career, was able to attract a considerably higher caliber of actress— not only as actresses, but even as pure cheesecake. Whereas the typical Sidaris starlet looks like the second-prettiest Hooters waitress in Miami, and acts accordingly, all three of the key Lost Empire gals are both impressively gorgeous and charismatic enough to make up for what they lack in conventional thespian ability. Raven Delacroix in particular is unforgettable, with a face like Barbara Steele, a body like Jayne Mansfield, and a wry sense of humor that makes Whitestar seem like she’s in on the joke of all the Movie Injun clichés that litter her dialogue. Also, Delacroix designed her own costumes, which are just magnificently garish and trashy. My favorite is the one that looks like a bikini made out of just the white leather fringed bits from one of Roy Rogers’s more regrettable shirts. Delacroix, Melanie Vincz, and Angela Aames can all handle themselves pretty well in a fight scene, too, even if nobody’s ever going to mistake any of them for Michelle Yeoh.

But the main thing that The Lost Empire has going for it is a bone-deep and totally unapologetic screwiness that recalls nothing so much as the movies that Sam Katzman produced for Monogram Pictures during the 1940’s. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll let a pair of examples stand for the overall trend. Dr. Sin Do has a sidekick called Koro (Robert Tessier, of The Babysitter and The Velvet Vampire), who performs a bewildering range of duties on and around his private island. Koro’s personality keeps shifting, though, along a sliding scale between “unctuous maitre d” and “sadistic drill instructor.” Also, you never know going from one appearance to the next whether he’ll have no eyebrows at all, or a pair of wild, Muppetish tufts projecting an inch or more from his face, and canted at exaggerated, Vampira-like angles to his orbital ridge. So is Koro supposed to be one inexplicably variable man? A pair of identical twins with strangely contradictory temperaments? An entire staff of clones, each individually tailored to some specific role? There’s no way to tell! Nor are things any less weird outside the influence of forgotten Lemurian sorcery. When Angel and Whitestar go to recruit Heather at the prison from which Wolfe proposes to spring her in accordance with a law that has never existed anywhere, they find her in the exercise yard, about to battle a fellow inmate known as Whiplash (Angelique Pettyjohn, from The Mad Doctor of Blood Island and Biohazard) for a prize consisting of each other’s monthly allotment of the illegal drugs smuggled in on the regular by unspecified means. Sure— we all know that’ll happen. And this contest is to be run under the watchful eyes of the guards, who consider these bouts the best entertainment to be had inside the walls. Okay— in fact, I bet Warden Zappa and Greta Lupino are kicking themselves right now for never thinking of that. But then the “referee” (Anne Gaybis, of Black Shampoo and The Human Tornado) gives the signal to begin, and Whiplash tosses aside her prison smock to reveal a studded leather corset and g-string, with a goddamned bullwhip wrapped around the waist! At that point, we are obviously no longer in any penitentiary on this Earth. Things like that keep happening all throughout the film— things that aren’t merely fantastical, but seem almost to be refutations of reality, in places where the film’s core premise in no way requires them to be. To return to the Sidaris comparison, it’s as if Wynoski drew an entire movie from the same pit of lunacy as Hard Ticket to Hawaii’s mutated cancer snake and body-building goon girl. This kind of shit is the reason why people become cinemasochists in the first place, you know?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact