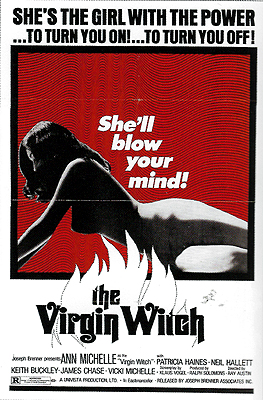

Virgin Witch (1972) ***

Virgin Witch (1972) ***

Allow me to remind you of Nicholas Schreck’s perfectly bitchy take on The Devil Rides Out’s Mormon Temple Picnic of a Satanic bacchanal: “the prudish censor insisted that proper British Satanists must keep all their clothes on whilst orgying.” It wasn’t just the lack of nudity that rendered that devil-orgy so laughable, either. The scene’s whole atmosphere was ludicrously staid, orderly, and well-behaved, without a trace of wildness or abandon anywhere, let alone danger or evil. It would have crashed and burned even in a much better movie, and in that one, devoid as it was of humor or self-awareness, it didn’t stand a chance. Yeah, well what a difference four years can make! In 1968, the forces of propriety were just beginning to lose their grip on the nation and its culture. The British Board of Film Censors could no longer stop a horror movie about a demonic cult from getting made in the first place (like they had in 1964, when Hammer first attempted to get a Dennis Wheatley adaptation off the ground), but they could still effectively demand that one be too stuffy and toothless to trouble the proverbial Mrs. Grundy. By 1972, however, there was no opposing the rising tide of liberalization, and nothing makes that plainer than a comparison between the aforementioned Hammer clunker and Tigon’s Virgin Witch. More than just frankly and explicitly erotic in its portrayal of occult rites, this movie avowedly takes the position that witchcraft comes in benevolent flavors as well as malign, and the characterization of its heroine implies an acceptance of power-seeking by fair means or foul that verges on actual Satanism!

The rather slender plot concerns a psychic named Christine (Ann Michelle, from Psychomania and Young Lady Chatterley) who wants to break into fashion modeling together with her sister, Betty (Ann’s real-life sister, Vicki Michelle, of Spectre and Queen Kong). After moving to London, where the two girls befriend and move in with a predatory Nice Guy called Johnny (Keith Buckley, of Excalibur and Dr. Phibes Rises Again), Christine is hired by agency boss and predatory lesbian Sybil Waite (Patricia Haines, from The Night Caller and The Clue of the Silver Key). Christine’s first assignment takes her to a remote country estate, where the squire (Neil Hallett, of Keep It Up Downstairs and 1000 Convicts and a Woman) not-so-secretly heads up a coven of white witches that seems to include everyone on his staff plus half the residents of the nearby village. It also includes Sybil, but to call her a white witch would be overstating the case by a fair margin. When Gerald— that’s the squire— learns of Christine’s innate paranormal abilities, he gets it into his head to induct her into the coven, and although the prospect initially gives the girl the willies, she decides upon further reflection that she likes the idea. Truth be told, the psychic flashes themselves always gave Christine the willies, so why not embrace something that promises to help her learn how to control them, and to put them to use? Sybil, however, recognizes that a witch with Christine’s talents is a potential threat to her position as the coven’s number-one female. Furthermore, Sybil’s jealousy is aroused when Christine turns out to prefer the attentions of Peter, the Waite Agency’s lecherous photographer (James Chase), to hers. Meanwhile, Betty and Johnny back in London learn enough about Sybil’s reputation to become concerned for Christine’s safety, but their visit to the manor goes in some unexpected directions. Christine is by now fully committed to all that Gerald’s circle represents, and she greets her sister’s arrival as an opportunity to strengthen her hand for the coming showdown with Sybil. She wants to bring Betty into the coven too, and to use the ceremony of her induction as the launching point for a coup against the older, darker witch. Mind you, Christine will have to become pretty dark herself in order to pull that coup off.

It took me by surprise when I started researching Virgin Witch, and found nothing but negativity and dismissal wherever I looked. None of my books on British horror films spend more than two paragraphs on it, and they all broadly agree with Jonathan Rigby’s assessment in English Gothic: “typical of the kind of sniggering and unflatteringly shot sex romps that began to proliferate on British screens in the early 1970’s.” Nobody online seems to have much more or much kinder things to say about it, either. Even the aforementioned Nicholas Schreck, whose book, The Satanic Screen, can usually be counted on to tease out even the feeblest point of interest in any occult-themed movie, found Virgin Witch worthwhile only as a delivery system for gratuitous nudity. Now to be fair, it certainly is that. Despite its subject matter, Virgin Witch is much more a sex movie than a horror film, and its creators clearly prioritized finding excuses to show skyclad cultists reveling in and around Gerald’s manor house above telling any kind of coherent story. But precisely because it does situate itself in the trackless frontier between horror and softcore porn in the manner of contemporary Continental European exploitation movies, it deserves recognition as part of a revolution in British cinema— one which the formerly all-powerful censors fought against tooth and nail, to shockingly little effect. Furthermore, if you look closely, Virgin Witch not only has a clear philosophical perspective (which is rare enough among movies of its sort), but a philosophical perspective directly at odds with that of the self-appointed moral guardians who were ultimately powerless to stop its release. Virgin Witch ought to get at least a little bit of respect for both of those things.

The revolutionary character of Virgin Witch’s eroticism should already be obvious enough, so I won’t belabor the point any further. Besides, the movie’s philosophical transgressions are much more interesting. Again, the easiest way to see what writer Hazel Adair and director Ray Austin have done here is to draw a distinction between their work and that of Hammer Film Productions. That studio, too, got in on the sex-horror action with The Vampire Lovers and its sequels, and in terms of simple explicitness, those movies are in the same league as Virgin Witch. Hammer, however, remained its fundamentally conservative old self despite the new liberties taken by the Carmilla trilogy. Even in Twins of Evil, which depicts patriarchal authority and vampiric devil-worship as comparably evil in their own ways, there’s no question but that the Karnsteins are the real villains, and the witch-persecuting Brethren are made to see the error of their ways in time to contribute to the vampire clan’s overthrow on relatively clear consciences. In Virgin Witch, though, we have not merely a witch as our protagonist, but one who ultimately rejects as artificial the distinction between white magic and black. The villain, meanwhile, earns that title not by working magic— or even by working evil magic— but by attempting to thwart the self-actualization of someone who is her natural superior. That’s where Virgin Witch starts verging on genuine Satanism. Instead of a conflict between good and evil or innocence and guilt, it pits Christine’s no-holds-barred drive for fulfillment against Sybil’s campaign to keep her subservient and controllable. Sybil’s sin isn’t that she exploits people, that she preys upon them sexually, or even that she’s prepared to kill them by supernatural means if it comes to that. After all, Christine does all those things too— using her own sister as a pawn in her struggle for the priestesshood; trading on her sexual allure to get what she wants from Johnny, Peter, Gerald, and even Sybil; casting a lethal curse against the elder witch in their final showdown— without it ever jeopardizing her status as the heroine! Furthermore, if I read the finale correctly, we’re meant to assume that Christine is destined to lead Gerald’s coven to new and greater enlightenment beyond their self-imposed constraints of good and evil, white magic and black. Hmm… Beyond good and evil… We’ve heard that before somewhere, haven’t we? If we define modern Satanism as Nietzsche with a sense of showmanship— and I do think that’s a fair shorthand summation— then it’s hard to see much difference between that and the belief system implied by Virgin Witch, no matter the quibbling one might do regarding the details of the coven’s ritual practices or whatever. And that’s fascinating, because nothing else on Adair’s or Austin’s resumés remotely suggests such sympathies. It’s entirely possible that they made one of the most authentically Satanist movies I’ve ever seen by complete accident!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact