The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1919) [unratable]

The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1919) [unratable]

I’ve been staying out of the business of reviewing short films, for the same reason that I don’t review cartoons. That is to say, I’ve been trying to avoid the old apples-and-oranges problem. Once the running time drops much below an hour— and certainly once it drops below 30 minutes— you really are dealing with a different art form, and the appropriate standards of evaluation must change. Considerations that matter a great deal in a feature film can become utterly meaningless in a short, while a five- or fifteen-minute movie can get away with things that would never, ever fly in a longer format. It can be hard enough to weigh the merits of features in radically different genres; taking on shorts too would mean introducing a degree of complication that I simply don’t want. Nevertheless, I think we need to talk about The Ghost of Slumber Mountain. The Ghost of Slumber Mountain was among the last (if not actually the last) of a series of silent shorts written and/or directed by Willis O’Brien to showcase his stop-motion animation technique. It is thus a piece of the foundation upon which the monster movie as we know it rests, a test-bed for the technology that would drive everything from The Lost World to Clash of the Titans. So in the same spirit as my review of Rick Schmidlin’s still reconstruction of London After Midnight, what I propose to do now is to discuss The Ghost of Slumber Mountain without making any attempt to rate it in the usual way.

As I will explain later, what survives today— and what was released to theaters in 1919, for that matter— is far from the complete film, and The Ghost of Slumber Mountain’s odd structure of flashbacks within flashbacks may have more to do with the massive editing that was inflicted upon it by producer Herbert M. Dawley than anything else. The story begins with a pair of young boys playing with their dog, Soxie, in the yard at the home of their uncle, Jack Holmes (Dawley himself). Holmes is an artist, writer, and adventurer who apparently makes his living from illustrated accounts of his travels, and when the boys tire of playing with Soxie, they rush home and implore their uncle to tell them a story from his exciting life. Holmes thumbs through his diary for a bit, and then begins his tale.

At some unspecified point in the past, Holmes had gone with a friend of his named Joe to the dense woodlands around Slumber Mountain, which stands at the edge of the Valley of Dreams. And yes, dear reader, I do believe that qualifies as a Hint!, and as we join the main body of the film, we’ll be keeping a sharp eye out for the point at which it becomes All Just a Dream. Anyway, after a day or two of hiking, hunting, and sketching, the two men come upon the cabin which was once home to a notorious hermit called Mad Dick, together with the cairn marking the dead loony’s burial site; the cabin is said to be haunted by its owner’s spirit. This is not Joe’s first brush with Mad Dick, either, for he once saw the hermit leave his cabin carrying some sort of strange optical instrument, with which he observed the peak of Slumber Mountain until what must have been well after Joe got tired of spying on him. Joe’s story spends the rest of the day lounging around in the front of Jack’s brain, and the latter man is still thinking about it off and on by the time he beds down that evening.

Yup. We’ve just crossed over into the dream. Jack believes that he is awakened by an unfamiliar voice calling from the depths of the woods, which he traces to Mad Dick’s cabin. Holmes goes inside, where he finds a proportionately enormous stock of paleontological paraphernalia— fossils, models, books, and at least one manuscript which we may assume to have been written by Mad Dick himself. He also discovers a padded case on the hermit’s desk, which contains what can only be that optical gizmo Joe saw the old man playing with on that long-ago afternoon. Just as Holmes opens up the case and removes the telescope-thingy, the cabin door slams shut in a gust of wind, and the ghost of Mad Dick appears before him! (Reputedly, that’s Willis O’Brien underneath all that unconvincing old-age makeup.) The ghost motions for Jack to follow him, and then leaves the cabin. When Jack catches up to the phantom hermit, he’s standing on the peak facing Slumber Mountain, toward which he instructs Jack to aim his exotic telescope. Astonishingly, the device allows Jack to see untold millions of years into the past, and he watches as Slumber Mountain’s prehistoric inhabitants enact the oft-invoked Struggle For Survival. Even more astonishingly, the window through the ages apparently opens both ways, for once the Tyrannosaurus finishes butchering that Triceratops it had been fighting, it turns its attention to Holmes, and chases him all the way back to the campsite! Good thing for him It’s All Just a Dream, huh?

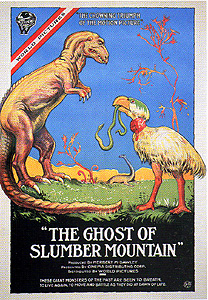

It’s worth pointing out that The Ghost of Slumber Mountain was not originally meant to be a short. Dawley had seen The Dinosaur and the Missing Link and some of the monster-comedy one-reelers which O’Brien had made subsequently for the Edison Company, and he approached the effects pioneer for assistance on a project of his own. The idea was to produce a somewhat more serious fantasy, involving a dangerous encounter between explorers and dinosaurs, and while reports of the completed film’s running time and plot outline vary, it seems clear enough that the original edit reached feature length (albeit possibly just barely), and was a much more involved undertaking than the Edison shorts. For one thing, O’Brien’s animation sequences in The Ghost of Slumber Mountain displayed a quantum leap of ambition and sophistication over the likes of Prehistoric Poultry. The models and scenery were much more realistic, and a few shots utilized such novel tricks as the substitution of thick gelatin for water, enabling an animated Brontosaurus to produce splashes and ripples when wading out into a pond. But more importantly, The Ghost of Slumber Mountain appears to have been the first movie to combine stop-motion animation with live action, and while this was done in an extremely primitive manner, it was nevertheless a groundbreaking departure from the pure animation of O’Brien’s earlier work. The Ghost of Slumber Mountain was a good three months in the making, and while its $3000 budget sounds like chump change today, it represented a fairly respectable investment in 1918, when work began. All things considered, it seems awfully strange that Dawley would ultimately decide not to use the vast majority of the footage he and O’Brien had shot (or at least not initially; some of that material is supposed to have turned up in 1920’s Along the Moonbeam Trail, but the disappearance of the latter movie makes it impossible to say what or how much), releasing the film only after whittling it down to a length variously reported at anywhere between eleven and twenty minutes. (The version I saw clocked in at just under nineteen.) Nor was the drastic cutting the only change that Dawley made. After the New York premier, the producer had the promotional artwork and main title display redone to eliminate any reference to Willis O’Brien. What’s more, he went so far as to claim that he himself had created and filmed the animated dinosaurs, circulating a ridiculous story of wood-and-canvas models seventeen feet tall! Needless to say, he was not widely believed, and the name of Herbert Dawley has faded into a richly deserved obscurity while O’Brien’s fame lives on.

Today, The Ghost of Slumber Mountain is interesting mainly as a trial run for a trial run; if The Lost World was the prototype for King Kong, then this movie was the prototype for The Lost World. That said, I believe it actually works a little bit better than its more famous successor, in that its narrative infrastructure isn’t stretched so dangerously thin. As with The Lost World, there’s little in the way of story here, but with only nineteen minutes of screen-time to fill, there doesn’t really need to be. It’s enough to get Jack Holmes up on the mountain with Mad Dick’s time telescope in his hands, whereas it would not be enough six years later simply to get Professor Challenger and his companions onto the hidden plateau in South America. Even the average quality of the animation is superior, although it must be admitted that this is due in large part to The Ghost of Slumber Mountain asking a lot less of its monsters than The Lost World does. The models themselves are primitive and poorly detailed (except for the Diatryma or Andalgalornis or whatever the hell the carnivorous flightless bird is supposed to be), and they don’t move much apart from the battle between the Triceratops and the Tyrannosaurus, but the limited animation is smoother than anything in The Lost World except the climactic dinosaur attack on London. The Ghost of Slumber Mountain may be nothing more than a curiosity, but it is a curiosity well worth investigating.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact