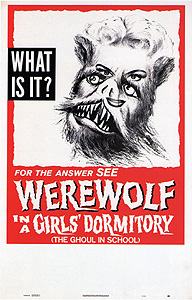

Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory / Lycanthropus (1961/1963) **

Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory / Lycanthropus (1961/1963) **

Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory makes a lot more sense when you understand what all these German-surnamed people are doing in what is generally described as an Italian film. It isn’t just Italian, you see— it’s Austro-Italian. As such, it was intended for the German-speaking market as much as for the Latin Mediterranean (or for that indispensable secondary buyer of Italian genre films of the 60’s, American television), which explains more than just all those Schells and Steiners and Lowenses and so forth. It also explains why Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory feels less like the Italian gothic you might expect than a German Krimi with a wolf-man standing in for the traditional masked master criminal.

Dr. Julian Olcott (Carl Schell) arrives at an unnamed girls’ reformatory to take up a position teaching biology. Technically that’s a little outside his field, for Olcott is a medical doctor. He’s been having a hard time lately getting a job, though, because of a serious scandal involving the death of a patient. The details will take their sweet time in emerging, but Olcott was at one point actually charged with her murder, and although he was acquitted by a court of law, the court of public opinion has apparently found the case for his innocence unpersuasive. It’s natural enough, then, that he should be getting his second chance at this particular institution. The director, Mr. Swift (Curt Lowens, of The Entity and The Mephisto Waltz), is a big believer in second chances generally, putting so much emphasis on the “reform” in “reformatory” that he refuses to countenance any notion of his facility as a place of punishment, stone walls and iron gates notwithstanding. Olcott’s advent causes a pretty big stir among the girls, as he seems to be the only male instructor on the staff, and he’s much younger and handsomer than Walter the groundskeeper (Luciano Pigozzi, from Castle of the Living Dead and Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eye, delivering a truly uncanny Peter Lorre impersonation) or Tommy (Joseph Mercier), the director’s valet.

Foremost among the girls who take an interest in the new teacher is Mary Smith (Mary McNeeran), which also has a certain logic to it. Mary sees no reason why her confinement to an all-female penal academy should interfere with her love life, and she’s been conducting an affair on the sly with Sir Alfred Whitehead (Maurice Marsac, of Captain Sindbad), the reformatory’s patron. She’s also a nasty piece of work, attempting to blackmail Sir Alfred into securing her release by threatening to make the ongoing dalliance public. Whitehead has foolishly been in the habit of writing her love letters, you see, so the affair has a paper trail a mile long. Anyway, on the night after Julian’s arrival, Mary sneaks out of the dormitory to see her lover, and to turn up the heat on him with regard to getting her turned loose. Two of the other girls— Priscilla (the preposterously adorable Barbara Lass) and her best friend, Sandy (Grace Neame)— witness Mary making her excursion. Curiously, though, they also spy one of the teachers, Leonora MacDonald (Maureen O’Connor), doing much the same thing. Maybe Miss MacDonald has a lover, too? Or perhaps she’s up to something more sinister. The moon is full this night, and on her way back from her rendezvous with Sir Alfred, Mary is set upon and torn to pieces by a werewolf! We see only the creature’s furry hands and baleful left eye with any clarity, so it could really be just about anyone for all we know at this point. Leonora, obviously, is one candidate. So, depending upon the werewolf lore in use here (about which we know nothing as yet), might be Sir Alfred, who returns home in a state of great agitation, long enough after Mary’s demise to afford him a chance to have caused it. And so, for that matter, might we suspect Whitehead’s wife, Sheena (Annie Steinert), who is wise not only to the affair with Mary, but to who knows how many similar fraternizations with other, previous inmates, and who has clearly come to detest her philandering husband.

The police inspector who comes the next morning (Herbert Diamonds) delves into none of that, however. The medical examiner blames Mary’s death on one of the wolves that have been making ever-bigger pests of themselves lately in the woods around the reformatory and the nearby village, and when Olcott cautiously avers that a wolf could have done the damage visible on the girl’s corpse, the detective is content to consider the case closed. He misses evidence that might have changed his mind by only the narrowest of margins, too, while going through the old “routine questions” act with Whitehead. It’s Priscilla’s turn to distribute the mail that morning, and when she discovers a letter addressed to the dead girl, she takes it upon herself to open it. The unsigned missive reads: “I cannot tolerate anymore threats! Your blackmail has gone far enough. Return my letters immediately or you will regret you didn’t!” Obviously this bears directly on the question of how and why Mary might have died, so Priscilla goes at once to Mr. Swift. Unfortunately, she doesn’t bring the letter with her, and even more unfortunately, she says aloud where she hid it after explaining the situation to the director. By the time Swift has rounded up the inspector, and Priscilla has led the two men back to the dormitory, somebody has pinched the incriminating document from her dresser. Inspector Scheisskopf leaps immediately to the conclusion that the girl is perpetrating some distasteful hoax, and threatens to arrest her for interfering in police business. We who are not idiots now have second mystery to ponder, however. Clearly the missing note was sent by Sir Alfred, but he can’t have been the one who stole it, because he was busy with the inspector at the time. The culprit would have to be somebody who had business within earshot of Swift’s office, because overhearing Priscilla’s tale is really the only means whereby anyone could have known where the note was stashed. Could it have been Tommy, perhaps? Or Walter? What about one of the teachers, like Leonora— or even Julian?

In any case, Priscilla is determined to get to the bottom of what she now believes to be Mary’s murder. An unexpected lead materializes when Sir Alfred, evidently incapable of quitting while he’s ahead, comes sniffing around for a new underage paramour, and then suborns Walter into approaching Priscilla with the suggestion that a discreet romance with a well-connected gentleman could be greatly to her advantage. Quickly putting two and two together, Priscilla pretends to acquiesce to the proposal, and arranges to meet Whitehead late that night at the cottage where he generally entertained Mary. Imagine her astonishment when she finds Mrs. Whitehead waiting for her instead! Sheena attempts to dissuade the girl from abetting Sir Alfred’s adulterous impulses by cautioning her that he’s a cad and a sadist, but because Sheena has completely misunderstood Priscilla’s aims, that warning has a very different effect from what was intended. So Sir Alfred’s a sadist, huh? Isn’t that interesting…? Even more interesting is what happens after Priscilla leaves the cottage to return to the dorms. First, somebody waylays Sheena, and injects her with some sort of drug. Then Priscilla encounters Julian in the woods; he says he was setting traps for the wolves, but should we believe that when we just now witnessed a crime that would require at least some basic medical expertise? Finally, Priscilla herself is attacked by the werewolf shortly after she and Olcott go their separate ways. She owes her survival to the timely intervention of Walter’s pet German shepherd, which charges in out of nowhere and drives the monster off before it can inflict more than superficial injuries. There’s still a body for the authorities to deal with come morning, however, because either the drug Sheena got shot up with or whatever befell her after it was administered turns out to have been lethal.

The next thickening of the plot occurs when Priscilla tells her story to Sandy. The latter girl makes the connection between Priscilla’s encounter with Olcott and the subsequent attack, and she denounces Julian to Mr. Swift. Swift, meanwhile, has just returned from the village, where the locals have decided both that their wolf problem is really a werewolf problem, and that Walter is the most likely suspect. They reach the latter conclusion on the basis of reports that the werewolf was severely wounded in the right arm while fighting the dog, but as Swift points out, Walter’s arm has been gimpy since the day he was born. Besides, why would Walter’s own dog attack him, werewolf or not? Julian, on the other hand, is sporting a fresh wound in the relevant appendage, which he attributes to an accident— although he pointedly won’t say what kind of accident. Olcott has a hell of a reply to Sandy’s accusation when Swift calls him in to answer it. He agrees wholeheartedly with the villagers that the killer wolf is actually human most of the time, and he claims that his wolf-trapping endeavors have been aimed at finding a cure for lycanthropy in the secretions of the animals’ glands! You remember that patient of his— the one he was charged with killing? She too had been a werewolf, and her death resulted from a self-administered overdose of a drug developed by Olcott to control her condition. Evidently lycanthropy is caused by a severe pituitary malfunction rather than by any sort of malign magic, and Julian believes that he is close enough now to success that if the werewolf were caught alive, he could restore it to normal. Note, however, that none of the foregoing quite absolves Olcott of suspicion, especially in light of his statement that among the symptoms of lycanthropy is complete amnesia regarding the periods of transformation. And even if we assume that Julian is no wolf-man, there’s still Sheena’s death to consider. True, there’s at least one person with a much better motive for killing her than any we might attribute to Olcott, but the details of her murder sure do look like something a mad scientist would dream up. Then again, remember Leonora MacDonald’s nocturnal prowling, and recall further that Swift got Olcott his job even though he was familiar with the circumstances of his professional disgrace. Familiar enough, maybe, to puzzle out the motivation behind the wolf-girl experiments? A doctor with a prototype lycanthropy cure sure would come in handy if Swift knew that someone on his staff was leading a double life on nights of the full moon.

Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory’s most serious handicap is probably that of unmet expectations. It sounds like a randy, silly monster romp, perhaps something along the lines of Horrors of Spider Island, and I for one would love to see that movie. Really, though, it’s something altogether different, and people simply don’t come to a film with a title like that because they’re in the mood for a talky, inelegant murder mystery. As a consequence, Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory is apt to face audiences who are ill-disposed to forgive its intrinsic faults or to detect any of its merits at all. The former category includes a lukewarm, flavorless porridge of a hero who progressively bogarts the limelight that more properly belongs to a plucky and engaging heroine; an overly convoluted mystery with at least one more red herring than the script can contrive any practical use for; and in its English-language version at least, a dense tangle of unworkable and frequently self-contradictory dialogue that makes virtually every character look like a nitwit in at least one major instance apiece. The merits, by contrast, are much subtler, and would be more difficult to appreciate even under ideal conditions. Indeed, some of them look like yet further defects at first glance. Take the character design for the werewolf as an example. It is undeniably unimpressive even by 1961 standards, looking even less specifically lupine than usual. But given the werewolf lore used here, that actually makes a great deal of sense. If lycanthropy is not a mystical curse but a glandular condition that manifests in harmony with the lunar cycle, then the “wolf” aspects become merely metaphorical, an artifact of pre-modern superstitious thinking attempting to come to grips with a reality beyond the reach of its understanding. In other words, a lycanthrope under this definition should just look like a hairy guy with snaggly teeth. (Mind you, that interpretation leaves us in need of a reason why glandular extracts from wolves would be of any special value in treating the affliction.) Another thing Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory gets right is to do as much with as many of the excessively numerous plot threads as the brief running time would allow. Even the ones that turn out to have no direct relevance to the wolf-man business are brought to some manner of resolution, however rushed or under-conceived. Counting Priscilla’s officially frowned-upon amateur sleuthing and Julian Olcott’s semi-secret lycanthropy research, there are no fewer than five separate agendas at work in this story, and the filmmakers exert good-faith efforts to do right by all of them. Particularly given the Italian involvement in Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory’s creation, that’s little short of astonishing. It’s also the movie’s most Krimi-like aspect, and therefore the one that’s most likely to throw a viewer who’s looking for a strictly conventional horror film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact