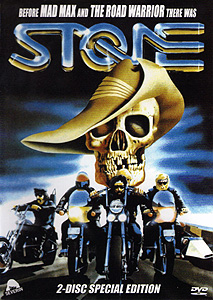

Stone (1974) ***½

Stone (1974) ***½

If anybody else was going to make American-style biker movies in the 60’s and 70’s, it would have been the Australians. This is because if anybody else was going to have American-style bikers in the 60’s and 70’s, it would also have been the Australians. To begin with, Australia shares with the United States the main geographical prerequisite for developing a cultish automotive culture— vast swaths of sparsely populated land traversed by highways suitable for motor vehicles, but ill-served by most means of mass transportation. Australia also shares with the US a cultural origin as a dumping ground for Britain’s malcontents, making it a similarly prime territory for breeding self-willed weirdos. And of perhaps the most specific relevance, Australia in the 60’s was led by men who were foolish enough to get roped into the Vietnam War, and although Australia managed to escape the worst of the Johnson-Nixon meat-grinder, that conflict became, if anything, even less popular there than it did over here. Australia thus had lots of men coming home fucked in the head from a war that wasn’t even their fight to an often hostile reception on a home front that had turned bellicose in its dovishness, and it had thousands upon thousands of square miles of tarmac-striated emptiness into which those men could retreat in the company of others who understood their sense of dislocation.

Meanwhile, the 1970’s saw both an abrupt loosening of Australia’s film-censorship standards (represented most conspicuously by the introduction of the adults-only R-rating for content that would simply have been disallowed in previous years) and a deliberate effort by the national government to revive the country’s long-languishing movie industry with tools like tax incentives and direct grants to domestic independent filmmakers. Thus began about a decade and a half in which conditions were nearly ideal for the creation of fiercely individual and often groundbreaking exploitation movies, and although official embarrassment frequently prevented the films from getting the exposure they deserved, the breadth and fecundity of Australian genre cinema in the 70’s and 80’s is impressive to say the least. There were horror films and sex farces and crime melodramas and even a kung fu movie or two made in collaboration with Hong Kong’s Golden Harvest company— and yes, there were indeed biker movies. (Or bikie movies, to use the regionally appropriate slang term.) The spotty distribution of Aussie exploitation flicks abroad makes it difficult for a Yank like me to say how many, but Sandy Harbutt’s Stone is the one that really matters.

That Stone was made with the cooperation of the Sydney Hell’s Angels is not the unusual thing about it. Plenty of American biker movies can make equivalent boasts, as the Angels craved novelty and would sign on for practically any film whose producers promised to get them drunk and/or high. No, Stone’s great distinction is that it was the first widely exhibited film (and possibly the first film, period) to deal expressly with the Australian bikie experience, and that it was made by people who were already on the inner margin of bikie culture in the first place. Harbutt, who both directed and co-wrote the picture, had been a motorcycle enthusiast for years, and had developed an intense interest in and respect for the hardcore bikies even if he was not one himself. For him, Stone was an exercise in “write what you know.” But perhaps even more importantly, as the project evolved, the circle of friends and professional acquaintances whom Harbutt had cast to play the featured gang-members came increasingly under the influence of the Angels who played the rank and file, as, for that matter, did Harbutt and his main creative partners behind the camera. The result was a counterculture movie whose honesty and authenticity (if not necessarily its accuracy in the strict sense) were nearly without precedent, and which would be embraced by the outsiders whom it depicted on a level that remains almost without parallel even today.

Like the rest of the developed world in 1974, Australia has a major pollution problem, and environmentalist politician Dr. Townes (Deryck Barnes, from Cars that Eat People) is amassing a groundswell of popular support by proposing to do something about it. Not everybody shares the mounting enthusiasm, however, and one dissenter— or maybe a dissenter’s hired agent— assassinates Townes with a long-range rifle at a rally in a Sydney park. The sniper (Lex Mitchell) does not work unobserved, though. A bikie gang called the Gravediggers had turned out for the rally, and one of their number— Toad, they call him (Hugh Keayes-Byrne, of Mad Max and Starship)— blunders into the gunman’s perch atop some sort of monumental building while in the throes of an acid trip. Toad is thus way too fucked up to trust his eyes when he sees the shooting go down, but the assassin has no way to know that. All his efforts just now must be directed toward escape, but we’ll all be certain that some connection exists with events in the park when Gravediggers begin dying in very deliberate-looking accidents during the coming days.

Perhaps surprisingly, the bikies’ deaths do not go unnoticed by the police, and the cops quickly reach the same conclusion about them as the Gravediggers themselves. They also have a pretty good idea what’s going to happen in the event that the Gravediggers figure out who’s behind it all, and when Undertaker (Harbutt himself) and the rest of the Gravedigger inner circle make it clear that the detectives handling the case will get no cooperation from them (maybe the overture would have gone better had it not interrupted the most recent victim’s funeral…), the authorities hatch a most unorthodox plan. There’s a detective on the force by the name of Stone (Ken Shorter, from Dragonslayer and Dragonheart: A New Beginning), and he doesn’t really fit in with the culture of the department. In fact, with his long hair and faggot clothes (excuse me— I seem to have been momentarily possessed by the spirit of Arthur Kennedy there), Stone could easily be mistaken for a bikie himself, and that’s just what his bosses are hoping will happen. Stone is to infiltrate the Gravediggers by whatever means he can manage, and use that privileged position to get to the bottom of the gang’s recent troubles. The rebel cop’s society-dame girlfriend (Picnic at Hanging Rock’s Helen Morse) hates the idea, but the occasional undercover assignment comes with the territory in his line of work.

Stone shows just how un-cop-like he is with the strategy he adopts for winning his way into the gang. No pose, no cover story, no bullshit— he just walks right into one of the bars that the Gravediggers frequent on their travels around New South Wales and tells them straight up what he’s been sent to do. Undertaker and his crew hold exactly the opinion of the police that you’d expect, and their disdain for the notion of operating with a police escort is exceeded only by their disbelief that Stone would come onto their territory to suggest it in the first place. But then somebody starts shooting through the bar’s windows with a crossbow, and Stone’s disciplined and decisive response to the crisis (to say nothing of the several Gravedigger lives saved by his swift but only partially successful counterattack) casts the issue in a new light. Undertaker puts it to a vote, and although there are still a good many nays tallied, a narrow majority of the gang assents to the arrangement on the condition of total secrecy regarding Stone’s true identity— it wouldn’t do, would it, to have word get out that a band of outlaw bikies knowingly had a lawman in their midst. Also, Undertaker admonishes Stone to “keep your spanners off of our molls!”

The plot kind of coasts to a halt at this point, and won’t resume its forward motion until nearly the end of the film. Instead, Stone devotes the bulk of its running time to a succession of vignettes about bikie life, as the eponymous detective acclimates himself to the Gravediggers and their ways. There’s a lot of hanging around smoking weed in the abandoned coastal fort that the gang uses as its headquarters, during which Undertaker, Toad, Septic (Dewey Hungerford), and Hooks (Roger Ward, of Fatal Bond and Lady Stay Dead) expound on the experiences that drove them out of straight society, and on the solace they derive from riding their bikes. There’s a street race between Stone and Captain Midnight (Bindi Williams), the Gravediggers’ most accomplished rider, establishing the detective’s fitness to ride with the pack. (In a commendably realistic touch, Stone loses the race, although he does well enough to make Midnight work for his victory.) We get, through the person of Gravedigger chaplain Dr. Death (Vincent Gil, from Encounter at Raven’s Gate and The Day After Halloween), a lightly sketched examination of the bikies’ more or less openly cynical use of Satanism to give themselves “minority religion” standing to conduct rites like weddings and funerals according to their own preferred customs. The marital misbehavior of Toad’s moll, Tart (Susan Lloyd), offers a bit of insight into bikie sexual mores. And naturally, we see a battle between the Gravediggers and a rival gang, which serves both to get the plot moving again (the assassin’s employers hope to exploit the clash by framing the other gang for the extermination of the Gravediggers) and to illustrate the bikies’ almost medieval conception of the roles of honor and violence in a man’s life. All that stuff is really the point of the film; the detective story is merely the device used to set it up.

To the extent that Stone has a problem, that’s it in a nutshell. This is a superb alternative lifestyle movie, but its anthropological aspects and its plotline are rather poorly integrated. A comparison between Stone and Suburbia is instructive in this regard. Both films use a slender story about a conflict involving a tribe of self-made outsiders to create a lens through which to examine how those outsiders live, and neither one really displays much interest from its creators in the story per se. But in Suburbia, many of the seemingly unconnected slice-of-life vignettes have plot points hidden inside them (as when the parents of the girl who was assaulted at the D.I. show turn up later at a town hall meeting about the menace posed by the TR kids), whereas Harbutt and co-writer Michael Robinson were content to put Stone’s nominal A-plot on hold for most of its length. It’s a frustrating novice mistake in a movie that is otherwise remarkably free of them.

In a movie with almost no plot, it is essential, obviously, to have something else of value to engage audience attention— exceptional acting, compelling characters, an engrossing sense of time or place, a strong visual or musical identity, something along those lines. Stone has all of those things, and collectively they more than compensate for its paucity of story. It’s no wonder that so many of the performers (most of whom had little or no prior screen acting experience) went on to become mainstays of Australian exploitation cinema. Sandy Harbutt, Hugh Keayes-Byrne, Vincent Gil, and Roger Ward may not be great actors in the usual sense, but they’re all absolutely perfect for the purposes of a quirky, low-budget action movie, and they’re visibly having a ball with the maladjusted mutants they play here. Gil’s Dr. Death especially is a hoot (not least because he looks like Coffin Joe dressed up as Alice Cooper for Halloween— or maybe vice-versa), and seeing Stone kind of makes me wish the Night Rider had had a bigger role in Mad Max. Meanwhile, Harbutt’s direction and Graham Lind’s cinematography combine to make the Sydney hinterland a character in its own right, to the extent that I now feel almost like I’ve been there, even though I have yet to set one foot on Australian soil. In any event, I’m confident that I’d recognize those locations that haven’t been built over yet (I’m given to understand that Sydney experienced a rather prodigious growth spurt during the 80’s) should I ever get the chance to see them in person. Billy Green’s music is an important factor, too, evoking the spirit of a mid-1970’s subtly but significantly different from any in my experience. The biggest thing that Stone conjures up, though, is a sense of how the bikies of the 70’s saw themselves, whatever the external realities of their lives. That’s what I was driving at earlier when I implied a distinction between Stone’s accuracy and its authenticity. Stone’s portrayal of the counterculture is obviously selective (for example, even outlaw bikies have to support themselves somehow, and yet we never see any indication that the Gravediggers have either jobs or any economically productive criminal engagements with which to keep themselves in food, fuel, booze, dope, and spare parts for their lovingly customized Kawasaki 900’s), but the selections themselves speak volumes about what life in an Australian motorcycle gang meant to the people who led it.

One final note before we take our leave of Stone: none of the home video versions available today— not even the double-disc deluxe edition from Severin Films— presents this movie as it was originally shown in Australian theaters in 1974. This state of affairs was arrived at deliberately. For whatever reason, Sandy Harbutt never watched the entire film through while he was overseeing the editing process (another novice mistake, perhaps understandable given that this was his first and only time in the director’s chair), so it wasn’t until the premiere that he really saw what he had created. Harbutt was rather aghast at the pacing, and when the time came to shop Stone around to distributors abroad, he took the opportunity to trim a full twenty minutes of what he considered extraneous meanderings. It is this truncated version that Harbutt regards as definitive, and thus the short edit is the one that has circulated ever since. A few of the excised sequences can be seen in Stone Forever, the nearly feature-length documentary on the film and its legacy that was produced on the occasion of Stone’s 25th anniversary (and which appears among the extras in the two-disc Severin edition), and for the most part, I have to agree that they don’t seem to add much. There’s one scene that really should have stayed, however. The Gravediggers’ military background might have seemed obvious to Sandy Harbutt; after all, they’re called the Gravediggers (“digger” in Australian military slang carries approximately the same meaning as “grunt” in its American counterpart), and their colors feature a skull wearing an Australian army slouch hat. But for foreign audiences whose understanding of Australian history and culture comes mainly from Crocodile Dundee and TV commercials for Foster’s beer and the Outback Steakhouse, the deleted conversation in which the principal bikies talk about having served in Vietnam or Korea would have conveyed otherwise inaccessible information that is vital for a full understanding of the movie. In other words, this is one case in which it really does pay to watch all the extras on the DVD.

This review is part of the B-Masters Cabal’s month-long look at counterculture exploitation movies. Click the link below to see how my colleagues are faring in their encounters with the various restive youth tribes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact