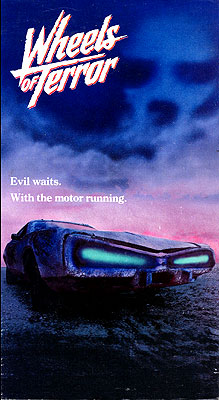

Wheels of Terror (1990) -**

Wheels of Terror (1990) -**

It’s funny how faddish cultural anxieties can be. Sure, something truly new and terrifying occasionally enters the world, like the threat of global nuclear annihilation during the Cold War, but more often the bogies that throw whole societies into a panic are things that had been there in the background all along. I could name any number of examples, but the one that’s on my mind right now is the hysteria over child abduction that swept the United States in the late 80’s and early 90’s. Don’t misunderstand me now; I’m not saying the fear was totally unfounded. Kidnapping has held a prominent place among the ways humans mistreat each other since time immemorial, and it would take an unimaginative parent indeed not to feel uneasy about that prospect once in a while. But that’s just it— there had always been sickos grabbing children off the street and doing unspeakable things to them, but from the way people carried on for a few years to either side of 1990, you’d think everyone in the country was out to steal somebody else’s baby. Where popular worries go, the popular media invariably follow, so of course those years also saw an uptick in the production of movies about kidnapping and other sorts adult depredation on children— especially, oddly enough, in the made-for-cable field. Wheels of Terror, originally broadcast on the USA Network, is one of the strangest manifestations of turn-of-the-90’s abductor panic I’ve seen. It’s like a hybrid rip-off of Duel and The Car crossed with a Lifetime Channel movie of the week, pitting an indomitable single mother against a kid-touching psycho who prowls the streets of her little town in the world’s angriest-looking customized Dodge.

Laura McKenzie (Joanna Cassidy, of Vampire in Brooklyn and Blade Runner) relocated two weeks ago with her pubescent daughter, Stephanie (Marcie Leeds, from Near Dark and Out of the Dark), from Los Angeles to the sleepy Arizona hamlet of Copper Valley. You know the deal: the Big City is no place to raise a child. Stephanie herself kind of hates her new environment, although she has managed to make at least one friend there. That would be Kim Donaldson (Kimberly Duncan), whose mother (Sharon Thomas Cain), appears also to be the one friend Laura has thus far acquired in Copper Valley. The local labor market must be pretty tight, because the only work Laura has been able to find is a gig driving bus #9 for Stephanie’s elementary school. In what might be this silly movie’s silliest detail, Luis (Gary Carlos Cervantes, of Nightmares and Howling VI: The Freaks), the mechanic for the Copper Valley Elementary School motor pool, recently finished hot-rodding the shit out of #9, outfitting it with a racing engine (is there such a thing as a racing diesel compatible with a commercial medium truck body?) that will push it to 110 on a well-surfaced straightaway, and apparently with brakes to match. The vehicle really ought to have some cheesy “Knight Rider”-style acronym at this point. How about “Bullshit Up-powered Sequential Stopper, or B.U.S.S. for short?

The trouble is, the McKenzies aren’t the only newcomers to Copper Valley. We never see the other guy except in the proxy form of his filthy and fucked-up 1974 Dodge Charger, but he establishes his credentials as a stand-in for both Duel’s mad trucker and The Car’s joyriding Satan in his very first appearance. That’s when he drives over a father stopped by the side of the road with car trouble, then speeds off with the victim’s little girl. That leads to Wheels of Terror’s one genuinely effective scene, as a highway patrol car comes upon the child walking dazedly down the highway some time later, the whole encounter played silent and shot from such a distance that we can just make out the hollow, haunted expression on the girl’s face.

Laura encounters the Molestermobile on what appears to be that same afternoon, when it makes a menacing orbit around B.U.S.S. as she takes a load of kids home from school. She sees it around town a number of times over the next few days, too, always being driven or parked in an intensely shady manner. So when Kim disappears from the schoolyard one afternoon, Laura goes at once to Detective Drummond (Prison’s Arlen Dean Snyder) to report the mysterious vehicle. Alas, Drummond is a nitwit, and doesn’t believe her testimony. On the other hand, maybe it’s more that the whole town is populated by nitwits, since Drummond claims that no one he’s spoken to has mentioned any strange cars meeting the Molestermobile’s description. Believe me, that custom Charger couldn’t be any more conspicuous if it had a big, light-up sign reading “MOLESTERMOBILE” on the roof, so if nobody else has seen it, then everyone else must be walking around with their heads up their asses. Even the kid the cops picked up on the highway before is no help, because she and another girl whom Drummond believes to have been caught and released by Kim’s kidnapper are both in catatonic states from which they emerge only to scream incoherently and uncontrollably. Still, they have it better than Kim, whose corpse turns up after a day or two in a pond on the outskirts of town. Between Kim’s fate and Drummond’s attitude, it’s no wonder that when the killer nabs Stephanie right in front of her mother, Laura gives him the full Mad Max, busload of kids or no.

That last busload of kids was a miscalculation on the filmmakers’ parts. Not because it makes the heroine guilty of mass child endangerment (although I suppose some viewers probably will take exception to that), but because it means that we have to spend the whole first half of the epic motor vehicle chase that climaxes Wheels of Terror listening to the little shits whine. I’m going to be hearing “Mrs. McKenzie! Please— stop!” in my dreams for the next week or so. You really feel the puling passengers’ extraneous presence, too, because the big chase is where Duel finally supplants The Car as an influence on this film. Duel is one of the leanest and most efficient movies ever made, and the looming need for Laura to unload those kids somewhere just draws that much more attention to how Wheels of Terror isn’t. So long as there are children aboard B.U.S.S., we know that Wheels of Terror is in no danger of getting down to business.

Switching between a Car rip-off and a Duel rip-off in midstream is a bad idea structurally, too, since it means that the plot essentially withers up and dies as soon as Laura engages B.U.S.S.’s Super Pursuit Mode. Steven Spielberg and Richard Mattheson could pull developing drama out of one continuous, feature-length car chase. Similarly, George Miller and Byron Kennedy could make a giant, sprawling automotive action sequence stand in for the final act of an otherwise conventionally constructed narrative. Writer Alan McElroy and director Christopher Cain will never be mistaken for any of those guys, however. Rather, these are the kind of filmmakers whose idea of foreshadowing is to play the opening credits over a scene of open-pit mining that bears no connection to anything else in the movie, telling us right up front what the arbitrary setting for the final confrontation is going to be. They’re the kind of filmmakers who lead up to said final confrontation with an extended two-vehicle demolition derby in soft focus and slow motion, set to a musical cue more appropriate to a romantic montage than a battle to the death between an enraged mother and the child-killer who just stole her daughter. They’re the kind of filmmakers who think an inexplicable racing engine is an adequate response to the objection that a school bus hardly seems capable of keeping pace with a muscle car, even one of the neutered muscle cars of the mid-70’s.

Wheels of Terror is minimally worth watching, though, just because it shines light on an aspect of exploitation cinema that most fans don’t ever think about. One normally thinks of sleaze as a masculine phenomenon; even when women are deemed sleazy, it’s usually because they’ve been caught catering to the untamed male id. Nevertheless, there’s at least one form of sleaze marketed specifically to female audiences, like an entertainment counterpart to the crassly reductive gender-branding typical of personal grooming products. Call it Sleaze For Her, or the Pastel Grindhouse— prurient enough for a man, but made for a woman! Sleaze For Her panders not to the libido, but to the maternal instinct. It trades in threats to children or to the family unit, with which it justifies a vision of heroism as violent and amoral as anything you’ll see in the late works of Charles Bronson. In the name of motherhood, the Pastel Grindhouse will sanction any barbarism or brutality, and by the same token, there is no limit to the atrocities that it will dangle over the heroine’s family in order to motivate a maternal rampage. (Note, however, that the atrocities in question are rarely depicted explicitly. Because the Pastel Grindhouse is primarily a television phenomenon, it’s an open question how much of that reticence reflects the assumed tastes of the target audience, and how much of it is due simply to the strictures of TV censorship.) The perpetrators of these horrors are usually men, although there’s some room for female villains in the home-wrecker mode, too: jealous stalkers, deranged ex-girlfriends, domineering mothers-in-law, etc. Non-villainous roles for men, meanwhile, are notably as limited and limiting as the roles for women in male-oriented sleaze-operas. Men in the Pastel Grindhouse may be well-meaning incompetents, unreliable absentees, or spineless pushovers, but the central conceit of Sleaze For Her is that the mother must always stand alone in the end. Mind you, the women get boxed in a bit, too, because the one thing this sensibility has no room for is voluntary childlessness. Consequently, the Pastel Grindhouse has pronounced tendencies to reinforce the grotesque modern notion of competitive motherhood, and to be positively vicious toward “bad” mothers. And of course, it was in the aforementioned era of widespread abductor panic that it really came into its own. Anyway, the point is, Wheels of Terror is loaded with Sleaze For Her, but as a horror/action hybrid, it applies the technique to a genre that is usually aimed squarely at men. Most Pastel Grindhouse movies are psychological thrillers or melodramas about families in disintegration; they certainly don’t devote their whole second halves to one giant car chase. Wheels of Terror can therefore be taken as a film for the woman who longs for a Lifetime Original Movie with a bit of adrenaline in its bloodstream, or as one for the man who wants to see how the other half are pandered to, but has no taste for tear-jerkers.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact