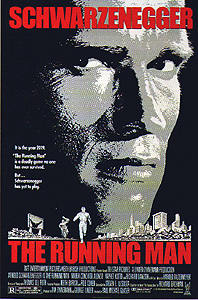

The Running Man (1987) -**

The Running Man (1987) -**

The people who adapted Stephen King’s writings to the screen during the first decade or so after his emergence made some odd, questionable decisions about how best to translate the stories into their medium, but at least it was always evident that they really had read what they were claiming as their source material. Even the worst of the lot— Children of the Corn, say, or Maximum Overdrive— were nonetheless immediately recognizable as what they were supposed to be. That has not been so much the case more recently, however, and The Running Man appears to mark the turning point after which a putative Stephen King movie might very well retain little more of its source than a few character names and a presumably marketable title. Upon reflection, there’s a weird sort of symmetry to that. The novel The Running Man was first published in 1982 as a paperback original under the pseudonym Richard Bachman, which King used from 1977 to 1984 for books that did not fit comfortably into his commercial persona as a horror author. (King resumed publishing sporadically as Bachman with The Regulators in 1996, but his use of the pseudonym these days seems to be less a function of genre marketing than one of boredom alleviation.) In other words, the first in-name-only adaptation of King’s work derives in theory from a novel that was King’s in everything but name.

In King’s telling, The Running Man was a gritty, noir-ish dystopia with a strong streak of early-70’s social radicalism. Its hero was an unemployable blue-collar malcontent whose desperation to raise money for the treatment of his pneumonic toddler led him to apply for a slot as a contestant on one of the sadistic game shows broadcast by the state-owned television service; his scores on the Network’s personality and intelligence tests earned him a place on “The Running Man,” the highest-stakes show of them all. King’s version of the titular program was like a macabre melding of “America’s Most Wanted” and Death Race 2000’s Transcontinental Road Race. Its contestants became fugitives for 30 days, liable to be slain on sight by every law enforcement agency in the country, to say nothing of the Network’s own in-house secret police force, and the viewers at home were encouraged to aid in the hunt with sizable cash prizes for verifiable sightings. On the upside, contestants (or more likely their next of kin) were rewarded with $100 for every hour they remained alive, plus $500 for every policeman or Network hunter they killed. The grand prize for surviving the full duration of the hunt was a cool billion dollars, but nobody had ever come close to attaining it. Compare all that, then, to the film version, in which protagonist Ben Richards is not merely a captain on the riot squad, but a helicopter flying captain on the riot squad, played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. In which “The Running Man” resembles not “America’s Most Wanted,” but “American Gladiators,” complete with silly costumes, signature weapons, and fighter personas that even the World Wrestling Federation would consider over the top. In which the darkest “happy” ending imaginable is replaced with something that makes the conclusion to Rollerball look credible. In which gritty noir styling gives way to all the pastel-and-neon tackiness that the late 1980’s could muster.

If Ben Richards is going to be an airborne riot cop, then I suppose it’s only fitting that we should meet him as he’s flying his helicopter over the scene of a riot. The location is Bakersfield, California, where the streets are thronged with poor folks trying to loot a grocery store, and Richards has just finished scanning the crowd from the cockpit of his gunship for signs that there’s anything bigger afoot than run-of-the-mill mass rowdiness. No one down on the streets is packing worse than a handful of improvised garbage projectiles, so Richards figures a stern “Move along, now” over the loudspeakers of a heavily armed chopper should suffice to take the situation in hand. Headquarters orders him to open fire on the rioters, however, and when he refuses, his crewmates wrest control of the helicopter away from him and commence the slaughter in his stead. Richards is sent to prison just as soon as he gets back on the ground, the great irony being that the crime for which he is officially convicted is the very massacre that he resisted carrying out.

Richards spends a year and a half in a typical sci-fi prison camp, complete with electronic perimeter and tamper-proof explosive collars. On the inside, he befriends a pair of political prisoners named Laughlin (Yaphet Kotto, from The Puppet Masters and The Monkey Hustle) and Weiss (Marvin J. McIntyre, of Short Circuit and Return to Horror High), and it is with their help that Richards eventually makes his escape. Nevertheless, Richards expresses no interest in joining his campmates’ nascent revolution, caring only to stay out of sight as far away from his old haunts as possible. Of course, he isn’t going to manage that for long without some money and a few provisions, so his first stop after taking his leave of la Résistance is the Los Angeles apartment complex where his brother lives. Whoops— correction: where his brother used to live. The current tenant is a youngish woman called Amber Mendez (Maria Conchita Alonso, from Predator 2 and Fear City), a jingle-writer for the advertising division of the official government television network. (The regime in the movie is less clearly thought out even than King’s rather loose-jointed tyranny, but in each case, we’re apparently dealing with a corporatist totalitarian state that takes a “no bread, but plenty of circuses” approach to public welfare.) Amber watches the news, so it takes her little time to recognize the huge man she finds prowling around her flat when she comes home from work. Her alert reaction doesn’t avail her much, though, and Richards has her tied to the exercise machine in her living room well before she can summon any help or attract any attention. In fact, so far as Richards is concerned, the unexpected encounter with Amber is an enormous boon, for it provides him with the makings of an actual plan. Using her money and travel pass (to say nothing of what looks an awful lot like the internet for a movie from 1987), he books a flight for two to Hawaii, then drags Amber along to the airport as both a cover story and a hostage. Once they’re at the airport, however… well, let’s just say that Amber is not the world’s most cooperative hostage or cover story.

Meanwhile, Damon Killian (Richard Dawson), high-ranking TV executive and host of “The Running Man,” is rather irritated at the apparent leveling off of his show’s ratings. “The Running Man” is still the most popular program on the air in its timeslot, but for the past several months, it hasn’t been gaining new viewers the way it used to. Killian thinks the answer to his stagnant ratings lies in recruiting a higher class of contestant, as the criminals the Justice Department has been sending him lately are an uncharismatic bunch, and present little challenge to his stable of Stalkers. Then he finds out about the escape of Ben Richards, the “Butcher of Bakersfield,” and about how Richards was just recaptured while attempting to flee the mainland in the company of a hostage who works for the network. Killian calls Justice at once, and arranges to have Richards brought to network headquarters for a personal interview. Apparently participation in this version of “The Running Man” is still technically voluntary, even though all the contestants are criminals, so Killian has to blackmail Richards into taking part. This he does by revealing that Laughlin and Weiss were also apprehended recently, and threatening to put them on in Richards’s place. Curiously (considering how little the ex-cop seemed to care about the two revolutionaries the last time we saw them together), Richards submits to Killian’s extortion. You can imagine his outrage, then, when showtime comes along, and Laughlin and Weiss are there on the set with him anyway.

As I said, this version of “The Running Man” works a little differently from what King dreamed up. Its playing field is strictly confined to 400 square blocks of city that were destroyed during a monster earthquake in 1997, and never properly rebuilt. The duration of the contest is a mere three hours instead of 30 days, and the grand prize is a pardon rather than an inhuman amount of money. Also, the contestants’ opponents aren’t just cops, network spooks, and citizen stool-pigeons. Killian has a staff of kitschy Stalkers at his disposal, all of them basically pro-wrestling heels armed with deadly weapons, and randomly selected members of the studio audience get to choose which of them are to be pitted against the contestants. There are four active Stalkers in the stable: Professor Subzero (Professor Toru Tanaka, from Revenge of the Ninja and Alligator II: The Mutation), whose hockey-themed gimmickry includes a razor-edged goalie’s stick; Buzzsaw (Bernard Gus Rethwisch, of House II: The Second Story and Wizards of the Lost Kingdom II), a biker with enough chainsaws to make Leatherface envious; Dynamo (Alone in the Dark’s Erland van Lidth), an opera-singing, lightning-shooting buffoon who looks like a Roman centurion being gang-raped by Christmas trees; and Fireball (Jim Brown, of Mars Attacks! and Original Gangstas), who has an asbestos jumpsuit, a flamethrower, and a rocket pack. Also on staff is a retired Stalker called Captain Freedom (Jesse “the Body” Ventura, from Predator and Demolition Man), who has the highest kill-count in the history of “The Running Man,” but is now merely the equivalent of a ringside commentator. Richards, Weiss, and Laughlin will end up facing all of the aforementioned foes eventually, as the ex-cop is a lot better at this game than Killian anticipated. Amber Mendez gets involved, too, for the discrepancies she observes between the news reports of Richards’s arrest at the airport and what she saw with her own eyes eventually start her wondering whether maybe Ben might have been right about the network’s wholesale invention of “truth.” She gets caught snooping around in the network’s clip room, just moments after she finds a disc containing undoctored footage of the Bakersfield Massacre, and she’s down in the arena herself before she knows what hit her. But Laughlin and Weiss at least have a slightly broader agenda than mere survival. The partisans’ leadership has discovered that the network’s master transmitter is hidden somewhere in the no man’s land of the “Running Man” arena, and they hope to find that transmitter and sabotage it, breaking the government’s media monopoly and giving the revolutionaries a chance to tell their side of the story to a nationwide audience.

Although I am somewhat charmed by The Running Man’s colossal naivety, it would be dishonest of me not to place a heavy stress on that “somewhat.” Earlier on, I drew a comparison between this movie’s giddy “viva la revolución” ending and the slightly less glaring absurdity that brings Rollerball to a close. What the two films have in common is an utterly implausible faith in the power of celebrities as a force for change, and an extraordinary failure to appreciate just how thoroughly they’ve stacked the deck against their cartoonish media heroes throughout the first five sixths of the running time. Where The Running Man goes Rollerball one sillier is in attempting to show the downfall of the Evil Empire instead of merely implying that it’s on the way. In doing so, the present filmmakers finally lose whatever grasp they ever had on the mechanics of their fictional world, conflating Killian with the network that employs him, and the network with the government for which it acts as a mouthpiece. When The Running Man inevitably turns into Commando for the final act, it abandons all sense of scale, and presents a pinprick attack against an organ of an organ of the system as a decisive triumph over the system itself. Stephen King sidestepped the issue completely by defining Richards’s activities as Running Man— even at their most grandiose, destructive, and attention-getting— almost purely in personal terms. But in Ronald Reagan’s America, it was an article of pop-culture faith that no problem was too big to be solved by a weightlifter with a machine gun.

Another major manifestation of The Running Man’s almost unbearable 80’s-ness is all the goddamned quipping. Ben Richards has a one-liner for literally every major act of violence he commits, and not a single fucking one of them bears even the faintest resemblance to wit. There’s nothing surprising about that, of course, as it took no time at all for Schwarzenegger’s terse pronouncements in The Terminator— originally intended to establish his character as less than human within the bounds of his extremely limited acting ability— to be retroactively misconstrued as signifying his badassery. Still, it doesn’t have to surprise in order to be disheartening, and after a quarter of a century of relentlessly quipping action heroes (so many of them indeed that even good writers like Joss Whedon have come to assume that it’s the normal state of affairs), it’s an eye-opener to go back this close to the start of the trend, and to see how lame and dreary the practice was even then.

The dialogue doesn’t get much better outside of Ben Richards’s mal mots, either. Admittedly, few people watch action movies for their scintillating employment of the English language, but it’s not like there’s a rule against trying, you know? The saddest dialogue moment of all has to be Laughlin’s death scene, which saddles Yaphet Kotto with this horrendous line: “Listen— we’re counting on you. Don’t let us down. I don’t want to be the only asshole in heaven…” I ask you— what the fuck does that mean?! Kotto is the one genuinely good actor The Running Man has to its credit, and this is the kind of crap it gives him to work with?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact