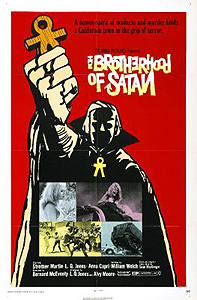

The Brotherhood of Satan (1971) ***

The Brotherhood of Satan (1971) ***

Given how utterly obscure The Witchmaker is today, itís rather astonishing to discover what looks for all the world to be a follow-up film, albeit not in the form of a direct sequel. Auteur theorists might have trouble at first recognizing The Brotherhood of Satan for what it almost certainly is, though, due to the absence from the latter movieís credits of William O. Brown, who wrote, directed, and produced The Witchmaker. Instead, the impetus for The Brotherhood of Satan appears to have come from L. Q. Jones and Alvy Moore, who had served as executive and associate producer respectively on the earlier production, together with playing supporting parts in front of the camera. Moore and Jones co-produced the second time around, while Jones received writing credit as well alongside William Welch (a recidivist contributor of scripts to Irwin Allenís television shows in the 60ís and 70ís). Jones is probably also the ďLQĒ in LQ/JAF, the only one of the several production companies associated with either The Witchmaker or The Brotherhood of Satan to be associated with both. Itís the writing that interests me the most, however, for although Jones officially made no contribution to The Witchmakerís script, The Brotherhood of Satanís is littered with callbacks to its predecessor. Even the Satanic liturgies employed by the two moviesí covens are largely the same. Does that mean that Jones had some small hand in writing the earlier film after all, or did he just like Brownís ideas so much that he appropriated them wholesale when he and Moore went back to the well two years later?

For three days, terrible things have been happening in the small Southwestern town of Hillsboro. Eleven children have vanished without a trace, and 26 people have died under circumstances ranging from the hair-raising to the utterly grotesque. And as if that werenít bad enough all by itself, no one has been able to get either into or out of Hillsboro in all that timeó every such attempt ending in bizarre and often deadly accidentsó and the whole town is now teetering on the brink of madness. Frankly, I expect the inhabitants would have already passed the tipping point if they had seen what we see just before the main titles. The Meadows family, seeking escape from the stricken village, run their station wagon off the road and down a steep embankment while swerving to avoid a young boy playing with a motorized toy tank in the middle of their lane a mile or two outside the Hillsboro town limits. Suddenly, a real tank appears out of nowhere and does the monster truck car-crush routine on the Meadows vehicle, leaving it and its occupants flattened beyond any but the most expert recognition. The boy then collects his once-more-ordinary toy, and walks off to join what we may assume to be a group of the missing kids.

Ben (Charles Bateman), his girlfriend, Nicky (Ahna Capri, from Enter the Dragon and Piranha), and his eight-year-old daughter, K.T. (I Dismember Mamaís Geri Reischl), are on their way to Benís motherís place to celebrate the little girlís birthday when they pass the compressed ruin of the Meadows family and their car. Being the dutiful and upstanding citizens that they are, they set off at once in search of the nearest town to report what they reasonably take to be a horrific traffic accident. This, of course, means that theyíre headed straight for Hillsboro. Ben and his family naturally donít realize how strange it is that they, alone in all the world, have been permitted to enter the village, but the townspeople certainly do. Perhaps inevitably under the circumstances, everyone the outsiders encounteró up to and including Pete the sheriff (Jones, who can also be seen acting in The Strange and Deadly Occurrence and The Beast Within)ó assumes that they must somehow be implicated in Hillsboroís inexplicable travails, and the three vacationers just barely make it back to the highway with their lives. It would appear, however, that whatever malign agency has closed off Hillsboro from contact with the outside world has specific need of Ben and/or his womenfolk, for they are driven from the road out of town by a kamikaze child, just as the Meadowses had been. Again, Ben, Nicky, and K.T. donít know enough to about the situation to grasp this, but they should count themselves lucky that nothing unspeakable pops out of the phantom girlís jack-in-the-box before she disappears!

The inhabitants of Hillsboro are rather friendlier toward the outsiders now that theyíre clearly trapped in town, too. Tobey the sheriffís deputy (Moore, also of Mortuary and the Scream you donít remember unless you, too, pay way too much attention to early-80ís slasher movies) even makes a point of befriending K.T., giving her a pretty creepy-looking stuffed monkey when he hears that itís her birthday. Pete puts the family up at the sheriffís station, and Ben thus becomes privy to the ongoing argument among Pete, Tobey, and Father Jack (Charles Robinson, of The Screaming Woman and Fer-de-Lance), the neighborhood Catholic priest, about the true nature of Hillsboroís problem. Pete doesnít really have a theory as such; he just protests over and over that the things the other two men propose are insane, and canít possibly be true. Tobey, for his part, is inclined to blame extraterrestrials for current unpleasantness, while Father Jack favors a supernatural explanation. Obviously, in a movie called The Brotherhood of Satan, Father Jack is closest to the truth. Thereís a coven of elderly witches at work in Hillsboro, led by the utterly harmless-seeming Doc Duncan (Strother Martin, from Sssssss and Nightwing), and theyíre gearing up for a roughly semicentennial ritual whereby they restore their youth and renew their immortality for another human lifetime. The key ingredient in the spell is thirteen children between the ages of six and nine yearsó one for each member of the coven, and with the same balance of male and female members. Thatís why Benís family were allowed into Hillsboro; the coven needed one more little girl than was available from the local population, and so they contrived to recruit one from outside the village. Clues to the covenís activities are readily obtainable between the police reports of the recent deaths and disappearances and the material on witchcraft in the books Father Jack still has from his seminary days, but Sheriff Pete will have to stop being so damned pigheaded if he and his associates are going to put those clues together in time to save Hillsboro (or K.T., for that matter).

To a greater extent than usual, the three stars that I have awarded The Brotherhood of Satan comprise an average value rather than a statement of consistent quality. The first half of this movie is much better than the second, with the audience kept scrupulously in the dark about whatís really going on in Hillsboro until nearly the hour mark. That strictly maintained mystery hooks and holds the audience, no two ways about it, but it comes at the cost of a momentum-killing exposition-dump that consumes the bulk of the second act. Building up a new head of steam takes time, and since time, in theory, is precisely the thing our heroes donít have by that point in the film, the climactic race between them and Doc Duncanís coven is never as suspenseful in practice as itís supposed to be. On the other hand, The Brotherhood of Satan concludes on maybe its strongest note of all, with a 70ís downer ending made doubly effective by the fact that none of the protagonists realize their defeat, nor probably ever will. Not only is it an unusually potent zinger, but it answers a question about the covenís prior operations that the part of my brain in charge of picking apart illogic and inconsistency was just beginning to formulate at the time.

In most other respects, The Brotherhood of Satan is a relatively unremarkable contribution to the flood of Satanically themed horror movies that washed over theaters in the late 60ís and early-to-mid-70ís, but it would be remiss of me to wrap up this review without saying a few words about Strother Martinís performance as Doc Duncan. Martin was belatedly coming into his own as an important character actor in those days, and what he does here goes a long way toward demonstrating why. In another point of resemblance to The Witchmaker, Duncan is not at all what one expects of a devil-worshipping warlock, but whereas Luther the Berserk diverged from the norm by projecting a primal, physical threat, Doc surprises by being so outwardly gentle and jolly. Itís the kind of wolf-in-sheepís-clothing characterization that Boris Karloff used to do so well, but even Karloff was never this disarmingly genial. Furthermore, except for one scene in which he presides over the Satanic equivalent of a heresy trial, the Doc Duncan known to the coven is just as mild and grandfatherly as the one known to his patients and neighbors. Combined with the knowledge that we meet Duncan and his followers during a rare period of crucial religious significance, Martinís portrayal of the coven-leader raises all sorts of intriguing questions about how these small-town backwoods Satanists conduct themselves the other 18,259 days of the half-century. Itís a persistent fact of human psychology that even the most thoroughly vile people tend to see themselves as fundamentally good, so The Brotherhood of Satan ends up looking remarkably insightful when it forces you to ask just how much and what kind of evil this cherubic old geezer could possibly get up to over the course of a typical day.