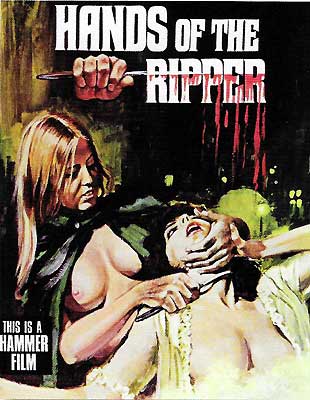

Hands of the Ripper (1971) ***½

Hands of the Ripper (1971) ***½

I have this crackpot theory that each of the countries whose filmmakers contributed significantly to the earliest development of horror cinema— earliest as in pre-1920, before anyone was even talking about horror cinema per se— brought something distinctive to the emerging genre that was initially unrepresented or just barely represented in the proto-horror films being made anywhere else. This isn’t really the time or the place to delineate or defend that theory in detail, but I bring it up because it seems to me that the British ingredient for that potluck primordial soup was the notion of true crime as a fit subject for horror. British filmmakers were far from alone in ripping subject matter from the headlines, of course, and detective stories had become a ubiquitous medium of entertainment throughout the developed world by the turn of the last century, but I’m not really talking about either of those things. I mean movies that don’t merely dramatize famous crimes, but revel in their ghastliest details— or at least the ghastliest details the censors would allow. Think of how often British horror movies have exploited Burke and Hare or the Maria Marten murder case, and of how early that tendency arose; Dick Winslow, for instance, filmed his version of Maria Martin, or Murder in the Red Barn all the way back in 1902. And then there’s Jack the Ripper, who’s spent a fair amount of time on British movie screens both in his own guise and under various diaphanous veils like The Lodger’s Avenger killer.

Hammer Film Productions, meanwhile, got almost as early a start in the business of historical horrors as was even theoretically possible for them. Phantom Ship, their second film, was an attempt to solve the Mary Celeste ghost ship puzzle as a body-count murder mystery. Made in 1935, it predated the firm’s wholesale embrace of the horror genre by more than twenty years. I find it curious, then, that Hammer left Jack the Ripper alone more or less (we’ll talk about the “less” whenever I get my hands on a copy of Room to Let) until 1971. Why did it take so long for the quintessential British horror studio to make serious use of such a quintessential British horror premise? Just as curious is what Hammer finally did with Saucy Jack once they got around to him. While Roy Ward Baker and Brian Clemens bridged the always-narrow gap between Jack the Ripper and Dr. Jekyll in Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde, Peter Sasdy and L. W. Davidson posited a daughter for the infamous killer in Hands of the Ripper. Neither film can remotely be described as a typical take on the character.

Hands of the Ripper begins by taking the mystery of the killer’s identity to a fascinating extreme. Although Jack the Ripper has intelligible dialogue, although his face is shown clearly in the very first scene, and although he is later recognized in a vision by a psychic medium, his true name is never spoken, nor is any specifically identifying information about him ever revealed. Furthermore, the actor playing the Ripper goes uncredited, and weirder still, all studio records pertaining to his casting and compensation have disappeared. Even director Peter Sasdy either doesn’t know or isn’t telling who the performer was. And yet hints at the killer’s motives are visible literally all over his face— a horrid constellation of suppurating lesions and old scars of same, like those that accompany the potentially madness-inducing tertiary phase of syphilis. Those sores are all we get by way of insight into the murderer’s crimes or personality, but they’re more than enough. Anyway, Jack almost got himself caught by a mob tonight, and the vigilantes raise such a ruckus charging through the streets with their torches and improvised bludgeons that he finds his wife and three-ish daughter, Anna, uncharacteristically awake when he returns home from a long night of slaughtering whores. Mrs. Jack the Ripper is no dummy, and she quickly realizes what’s what when she notices the blood all over her husband’s gloves and overcoat. Obviously the Ripper can’t have her letting his cat out of the bag, so he gets out his murdering knife once again. Strangely, however, he doesn’t turn it on his daughter afterward, even though she just watched him slicing Mom to pieces. Instead, he simply leaves Anna behind when he packs up and goes into hiding however and wherever he does that. Maybe he figures she’s too young for the memory to stick permanently in her brain, or perhaps he’s just counting on nobody taking seriously anything a three-year-old might say.

Fifteen years or so later, Anna (Angharad Rees, from Baffled! and The Curse of King Tut’s Tomb) is living under the guardianship of a widow (or perhaps divorcee) called Mrs. Golding (Dora Bryan, of Screamtime and Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire). As we all know, single women had limited options for supporting themselves in Edwardian England, so Mrs. Golding earns her living as a shyster medium, faking manifestations of the spirit world with the aid of her foster-daughter. Tonight’s séance is being conducted mainly for the sake of Mr. and Mrs. Wilson (Barry Lowe, of The Creeping Unknown and Enemy from Space, and The House in Nightmare Park’s Elizabeth MacLennan), who wish to speak to their dead daughter, but there are three others in attendance, too. Two of those are Dr. John Pritchard (Eric Porter, from The Lost Continent) and his son, Michael (Island of Terror’s Keith Bell). Dr. Pritchard is a dedicated debunker of spiritualist flimflam, and he’s here in the hope of catching Mrs. Golding in the act of defrauding her customers. He doesn’t come away with proof positive, but his discovery of Anna hiding behind a curtain in a place that would permit her to influence the events of the séance convinces him thoroughly enough. The final guest is Mr. Dysart (Derek Godfrey, from The Vengeance of She and The Abominable Dr. Phibes)— a member of Parliament, if you can believe that. Like the Wilsons, Dysart is a customer of Mrs. Golding’s, but he isn’t here to have his fortune told or to chat with deceased loved ones. As soon as the others have all left the building, he hands the lady of the house an impressive sum of five guineas— the price that Mrs. Golding has set for Anna’s virginity. The transaction doesn’t go according to plan, however, for Anna lapses into a sort of trance when she sees the lights of her bedroom reflect off of the obviously expensive brooch which Dysart offers her. Anna doesn’t consciously remember this, but the firelight played among the glass pendants of the chandelier in her old flat in Whitechapel exactly the same way at the moment when her father stabbed her mother to death. When Mrs. Golding comes upstairs in response to Dysart’s increasingly heated haranguing of the near-catatonic girl, Anna regains enough of her animation to run her foster mother through with a fireplace poker, pinning her body to the door. Dr. Pritchard, still waiting for a cab on the other side of the street, sees Dysart fleeing the scene a moment later.

It’s odd, then, that when everyone in attendance at the séance is called in to testify for Scotland Yard, Dr. Pritchard covers for Dysart, whom the inspector working the case (Norman Bird, from The Black Torment and The Final Conflict) plainly regards as the prime suspect. Equally strange, in its way, is Pritchard’s eagerness to take over guardianship of Anna. The doctor’s motives begin to come into focus, however, when Michael and Mrs. Bryant (Marjorie Rhodes, of Footsteps in the Fog), the Pritchard family housekeeper, pick up Michael’s fiancee, Laura (Jane Merrow, from The Horror at 37,000 Feet and The Woman Who Wouldn’t Die), at the train station. Laura, or so it is implied, has spent the past year at a home for the blind, learning to cope with her recently acquired disability, and during the couple’s catching-up conversation on the way home, Michael mentions that his father has lately become a disciple of an Austrian doctor by the name of Freud. Okay. Now I get it. Dr. Pritchard knows perfectly well that only two people— Dysart and Anna— could possibly have killed Mrs. Golding, and careful observation has led him to suspect the latter. Given the girl’s social standing, this is therefore the perfect opportunity for Pritchard to make a controlled scientific study of the homicidal mind, perhaps to blueprint the mental machinery of murder. By covering for Dysart, he puts himself in a position to extort the M.P.’s silence, so that he can carry on his work in peace.

Peace is going to be in short supply, though, for reasons that have nothing to do with Dysart or Inspector Whatshisface. For one thing, Michael and his father did not consult each other on the subject of moving girls into the house, and they each assume that theirs is going into the room once occupied by the late Mrs. Pritchard. Laura and Anna seem to get along okay at their first meeting, but the men in their lives are most annoyed with each other over the misunderstanding. And to look at things strictly from the doctor’s point of view, it really is a hassle having one more person from whom to hide what he’s up to in the lab. But a bigger difficulty presents itself on Anna’s first night at the Pritchard house, when she blows off an evening of dinner and dancing with her hosts to murder Dolly the maid (Marjie Lawrence, from I, Monster and I’m Not Feeling Myself Tonight). It’s a lot like what happened to Mrs. Golding. First, Dolly presents Anna with a garish necklace from the collection of her dead mistress, precipitating another shallow trance. Then, oblivious to Anna’s bizarre mental state and overcome with excitement at how gorgeous she looks done up in Mrs. Pritchard’s gown and jewelry, Dolly impulsively kisses her on the cheek. At that, Anna suddenly hears the forgotten voice of her father whispering in her ear. She smashes the hand mirror she was holding into a highly effective shiv, and buries the jagged end in the other girl’s throat. Dr. Pritchard has a lot of cleaning up to do when he comes home early to see what’s taking Anna so long.

Dysart butts in soon thereafter, with an unwanted recommendation for how Pritchard might proceed in his research. The M.P., you’ll recall, saw with his own eyes the change that comes over Anna when she kills, and the more he thinks about it, the stronger grows his impression that her murder-trance is something more than natural. Consequently, he thinks Pritchard should take Anna to see Madame Bullard (Jekyll & Hyde’s Margaret Rawlings), the psychic who used to do readings for Queen Victoria herself. Unsurprisingly, Pritchard has no intention of taking Dysart’s advice, but then the M.P. reminds him that extortion is a game two can play. He’s sure that Pritchard is on the wrong track with this psychoanalysis shit, and he refuses to stand by when someone as dangerous as Anna is on the loose. And as if to make Dysart’s case for him, Anna kills again that night, wandering off to Whitechapel when Michael and Laura interrupt a hypnotherapy session, and catching the attention of lesbian whore Long Liz (Lynda Baron) with predictably gruesome results. Pritchard grudgingly takes Anna to see Madame Bullard the following day, but scoffs when she informs him that his homicidal ward is the daughter of Jack the Ripper. He does learn something useful from the consultation, however, for the psychic inadvertently trips Anna’s crazy switch during the session. For the first time, Dr. Pritchard gets to see the girl in action, enabling him at last to begin attacking the problem on a truly informed basis. Not that doing so will accomplish much beyond getting himself killed and putting everyone he cares about at immediate risk of same…

Hands of the Ripper is a remarkably prescient film, anticipating two trends that would transform the popular conception of horror movies in the decade to come. On the one hand, it’s a possession story two years before The Exorcist. Although the film never comes down decisively on either side of the question of whether Anna is literally harboring the spirit of her murderous father, or is merely a case of multiple personalities, the distinction matters little in practical terms. Either way, there’s something evil inside her, and bloody havoc results whenever that evil manifests itself. Furthermore, in a really striking foreshadowing of The Exorcist and its imitators, the savant who attempts to dispel the malignancy within Anna succeeds in the end only at the cost of his own life. Meanwhile, the nature of Anna’s “demon” is such that Hands of the Ripper is also as much of a proto-slasher as any giallo. In fact, there’s one shot, when Dr. Pritchard finds Dolly’s corpse, which strongly suggests that director Peter Sasdy had seen Blood and Black Lace before getting to work on this picture. This may be the last time Hammer were actually ahead of the curve.

At the same time, though, Hands of the Ripper carries on some longstanding Hammer traditions with admirable astuteness. Most obviously, it shows that period settings could indeed have some life in them yet, and needn’t be discarded just because nobody else could think of anything interesting to do with them. What was wanted were simply some fresh faces in front of the camera, some fresh ideas behind it, and a willingness to keep pushing the limits now that censorship was in a worldwide state of rout. Hands of the Ripper provides all those things. Much as I adore Peter Cushing, it is absolutely vital to this movie’s success that somebody else is playing the hubris-driven scientist here. Casting Eric Porter as Pritchard allows our suspicions of the character to grow naturally, without the specter of Victor Frankenstein looming over them from the word go, while still maintaining a high standard of artistry in the performance. Keith Bell as Michael, meanwhile, is a rather more serviceable young male than Hammer was used to settling for in this period— although I am somewhat perplexed at the way he’s made up to look exactly like Edgar Allan Poe. That’s the sort of detail that feels like it ought to mean something, but I can detect no sign that it actually does. Most startlingly, Hands of the Ripper has in Angharad Rees and Jane Merrow two leading ladies of genuine ability, cast in parts that are worthy of their talents. Rees especially should have gone onto the short list of actresses to call when something more than a big pair of boobs was required, since she proves herself equally adept at childlike innocence and malign savagery. (Mind you, to imagine that short list presupposes that anyone at the studio was writing such parts in the first place, which turned out to be a whole separate problem…) As for pushing the limits, Hands of the Ripper was truly state of the art in gruesomeness at the time, with at least two murder scenes that would have drawn attention even in the notoriously gore-soaked early 80’s.

What is perhaps less apparent— and this is where the fresh ideas come in— is that Hands of the Ripper stealthily continues the work of the Hammer mini-Hitchcocks, and plays the psycho-horror card to much greater effect than, for example, the following year’s Fear in the Night. The mini-Hitchcocks had long since mined out the old Diabolique vein, and four successive riffs on What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? had left crazy old ladies similarly exhausted. A new premise was called for, and a psychiatrist who assumes, in his Victorian arrogance, that he can tame the child of Jack the Ripper certainly had the benefit of novelty. It also had the benefit of permitting, through the character of Dr. Pritchard, a thorough examination of upper-class paternalism. Writer L. W. Davidson made Hands of the Ripper perhaps the most overt display yet of the aristocrat-baiting that Hammer had indulged in with greater or lesser circumspection ever since The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957. Pritchard, after all, is a gentleman doctor, and he seeks to make of Anna not merely a non-murderess, but also a lady. Furthermore, the victims of Anna’s crimes whom Pritchard so cavalierly disregards (is it still a pun when the intended double meaning is built right into a word’s etymology?) are mere commoners, with the sole exception of Madame Bullard. And in the most vicious single twist of Davidson’s class-conscious knife, Dysart— who, you’ll recall, sets the whole bloody business in motion by attempting to buy a teenager’s virginity from her unscrupulous legal guardian— suffers no punishment of any kind. He’s an M.P., you know, and riffraff like Anna have no rights that an M.P. need respect. In the 70’s, as we well know, horror cinema became subversive in ways that it never was before, and rarely has been since. With Hands of the Ripper, Hammer showed that they could subvert with the best of them, if only they could be arsed to try.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact