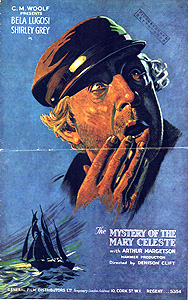

Phantom Ship / The Mystery of the Mary Celeste / The Mystery of the Marie Celeste (1935) **

Phantom Ship / The Mystery of the Mary Celeste / The Mystery of the Marie Celeste (1935) **

It was just about the perfect real-life locked-room mystery. On November 7, 1872, the half-brig Mary Celeste set sail from New York, bound for Genoa with a hold full of raw alcohol packed in wooden barrels. In addition to the captain, his wife, and their little daughter, the ship carried a crew of seven sailors. A bit less than a month later, the Mary Celeste was spotted some 400 miles east of the Azores by lookouts from the Dei Gratia— the American ship was in excellent sailing trim, tacking perfectly to catch the wind and with masts, rigging, and fittings in fine condition, but there was not a single person, alive or dead, to be seen aboard. The latest log entry was dated November 24, ten days before sailors from the Dei Gratia boarded to investigate, but both the state of the ship and the behavior of the winds during the preceding week and a half made it clear that somebody had to have been onboard much more recently than that. There was no evidence of a struggle, nothing to indicate that the Mary Celeste had fallen victim to pirates (the cargo in the hold was untouched), more than enough food and water to last for the remainder of the scheduled voyage, and indeed no clue at all to explain the absence of the crew beyond the empty rack for the yawl boat mounted above the main hatch. The British and American maritime authorities who investigated the case came to no persuasive conclusions, and to this day, the mystery of the Mary Celeste remains unsolved. Naturally, historians, novelists, filmmakers, and crackpot conspiracy buffs have been pouring out a steady stream of speculations, ranging from the contrived to the preposterous, ever since.

Among the more interesting of those speculations (which, for the record, falls closer to the contrived end of the spectrum than the preposterous, although it plays fast and loose with the facts of the case) was the brainchild of British director/screenwriter Denison Clift. Mind you, the hypothesis Clift offered up in The Mystery of the Mary Celeste (released in the US as Phantom Ship) is not especially clever or remarkable in its own right, as it takes the form of a fairly typical 30’s body-count mystery which is fundamentally compromised by the fact that the killer’s identity is obvious long before the first murder is even committed. No, what makes Phantom Ship worthy of attention is the fact that it was the second movie released by Hammer Film Productions, and the first that could plausibly be characterized as a horror film— twenty years before that studio transformed itself into Britain’s top-ranking peddler of vampires, mummies, and renegade scientists. Not only that, Phantom Ship enjoys the distinction of being among the first movies Bela Lugosi made over in England. In and of itself, Phantom Ship is nothing special, but it’s absolutely intriguing as an early harbinger of what was to come for the studio that produced it.

Captain Benjamin Briggs of the Mary Celeste (Juggernaut’s Arthur Margetson) has a problem. He’s scheduled to ship out for Genoa with a cargo of alcohol at first light, but he’s far short of the ten men he needs to complete his crew, and his first mate, Toby Bilson (Edmund Willard), has had no luck drumming up interest in the dockside pubs. Part of the reason why is that the Mary Celeste has a reputation as a bad-luck vessel, but if you’re asking me, I’d say the recruitment shortfall has even more to do with the obvious fact that Bilson is a mean-tempered son of a bitch while the captain himself is a smarmy dickweed. That doesn’t occur to Briggs, however, and before long, he’s out at the tavern owned by Horatio Sprague (Wilfred Essex), trying to find a few willing sailors. Actually, both men seem to have a rather loose definition of “willing,” despite the captain’s professed disdain for the practice of shanghaiing, and most of the seamen who sign up have to be browbeaten into doing so. There’s one man under Sprague’s roof who is outright eager to get aboard the Mary Celeste, however— a one-armed, middle-aged foreigner named Anton Lorenzen (Bela Lugosi, in what may be the most against-type role of his career), who gets a strange, faraway look in his eyes when he hears the name of the ship and its first mate from the innkeeper, and immediately launches off on a tirade about a time six years ago when he was shanghaied from his home in Europe. There’s no way it’s anything but a bad omen when he signs Bilson’s crew register under the assumed name of “Gottlieb.”

Now it’s possible one or two of you have questioned my assessment of the captain’s character— Denison Clift certainly gives no indication that he considers Briggs to be anything but a stand-up guy. Permit me then to enter into evidence Briggs’s fiancee, Sarah (Shirley Grey), and the circumstances attendant upon their engagement. Briggs asks Sarah to marry him right before he reports to the dock, and he even expects his intended bride to join him on the voyage across the Atlantic. Meanwhile, Sarah has already been proposed to by another man, Captain Jim Moorhead (Clifford McLaglen), who happens also to be Benjamin’s best friend, and though she has not yet given him a definitive answer, it’s obvious that Sarah’s been giving him serious consideration. For the sake of comparison between the two suitors, Moorhead has been in negotiation with a shop owner in the shipping district, angling to start himself a career that wouldn’t require Sarah to make the choice between enduring long periods of separation and accompanying him aboard ship when he goes to sea, whereas Briggs thinks nothing of demanding that the love of his life spend months at a stretch cooped up in a soggy wooden box as the only woman amid a mob of surly, horny, ill-mannered, violent men. Nevertheless, it’s Benjamin that Sarah agrees to marry, demonstrating that the Worst Guy Available Law was already in effect in the 1870’s. Soon thereafter, we see what friendship means to Briggs, as he goes so far as to gloat about Sarah’s acceptance of his proposal when Moorhead swings by a moment later to tell Sarah that his purchase of a dockside storefront is looking like a done deal. Then Benjamin has the nerve to ask Jim to lend him one of his men the next morning, when even Bilson’s last-second impressment of a couple of semi-conscious drunks fails to bring the crew up to full strength. So you see what I mean about Briggs being a smarmy dickweed, don’t you? Frankly, I can’t say I blame Moorhead when he bribes seaman Volkerk Grot (Herbert Cameron) to ship out on the Mary Celeste and see to it that something ugly happens to Briggs on the sea lanes to Genoa. (Ah, yes— our old friend, Clupa harengus ruber, the Atlantic red herring. I’m afraid, Mr. Clift, that it’s already much too late for that.)

Grot makes his move very quickly, attempting to incite mutiny among the men over the leathery salt meat and the maggot-ridden biscuits that comprise the crew’s rations, but nobody takes the bait. Genuinely disgusted about the food, above and beyond the dictates of his mission for Moorhead, Grot goes back to Briggs’s cabin to air his grievances (Briggs to Grot: “Now what’s the problem here? I know it’s not the food— I always feed my men well.” Smarmy dickweed…), but all he gets for his troubles is a flogging from Bilson. Later (and by this point, I think it’s safe to say that he’d be up for something similar even without the $38 and the promised promotion from his real boss), Grot tries to waylay the captain while he’s standing the night watch at the helm, but he is stopped by Tommy Duggan (George Mozart), who jumps Grot from behind at the crucial moment and sticks a knife between his ribs. That’s only the start of the trouble, however. While all other hands are on deck battling a violent storm a few nights later, Tom Goodschard (Dennis Hoey, from She-Wolf of London and Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man) sneaks into the captain’s cabin, and tries to rape Sarah; it’s “Gottlieb” who saves her, and I must say, the man’s an awfully capable fighter for a one-armed pentagenarian. From then on, deaths are an almost nightly occurrence, as somebody begins garroting and strangling his way through the crew. Briggs’s heavy-handed efforts to unmask the killer do nothing but stir up more hatred among the men (smarmy dickweed…), and we in the audience can only hope that Denison Clift won’t put him aboard the missing rowboat and let him reach safety from the murderer’s justly evoked wrath.

I have a sneaking suspicion that Denison Clift thought we were all retards. There would seem to be no other explanation for his insistence upon pretending that there was any mystery to The Mystery of the Mary Celeste after the one person other than Anton Lorenzen who could have a motive for murder is killed himself. And really, even before that, we know perfectly well that Lorenzen will be the one emptying out the ship’s billets— there’s just no other way to interpret that scene at the pub when the mention of Toby Bilson’s name brings years’ worth of hitherto-impotent rage boiling up out of the one-armed man. Uncertainty about the killer’s identity isn’t strictly necessary, of course, but for Phantom Ship to have worked as an out-and-out horror film instead, it would have helped to make a slightly bigger deal out of the murders themselves. As it is, Briggs and his crewmen just keep finding dead guys lying around whenever they go to change shifts for the overnight watch. What keeps Phantom Ship from being a total waste of time is how totally unlike other contemporary murder mysteries it is when it comes to setting and tone. It has a spirit of grubby authenticity that deflects the focus away from the clumsy non-mystery and the shortcomings of the movie’s horror aspects. There’s so much battling against the elements and scrambling around in the rigging and rebelling against the casual tyranny of the captain and his mate that you soon end up relating to Phantom Ship mostly as a seafaring adventure movie that just happens to have a serial killer in it; a quick look at Clift’s resume (especially as a screenwriter) suggests that this is probably not an accident. And as is only appropriate given the movie’s inspiration, another effect of the emphasis on the minutiae of life at sea is that the Mary Celeste becomes almost a character in its own right. It seems to me that what we’re seeing here is a sign that even in the very beginning, Hammer was attracting people who were willing and able to do things a little differently from what an audience accustomed to Hollywood fare would expect. The results might not quite gel in Phantom Ship, but they certainly would two decades down the road.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact