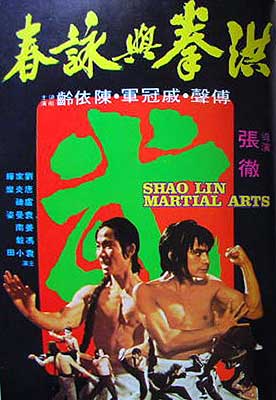

Shaolin Martial Arts / Five Fingers of Death / Hong Quan yu Yong Chun / Hung Kuen yue Wing Chun (1974) **Ĺ

Shaolin Martial Arts / Five Fingers of Death / Hong Quan yu Yong Chun / Hung Kuen yue Wing Chun (1974) **Ĺ

It turns out that making overall sense of the Shaolin Temple movies that Chang Cheh directed for Shaw Brothers in the 1970ís is going to be even more complicated than I realized, because not all of them can be meaningfully considered series entries like Heroes Two, Men from the Monastery, and Five Shaolin Masters. Others, like Shaolin Martial Arts, stand mostly on their own, having no direct narrative connection to the legend of the Shaolin Temple or the heroes and villains associated with it, and concern themselves merely with the templeís supposed legacy as a wellspring of Southern Chinese kung fu. My best guess is that Shaolin Martial Arts is set most of a century after the burning of the temple (whichever date we choose to accept for that event), by which point everyone who personally participated in the drama of its destruction is dead and buried. And although the need to stand up against Manchu oppression still figures prominently in this movieís story (the Qing Dynasty, after all, persisted until 1912), the primary conflict here takes place between rival kung fu schools that have taken sides in the ethno-political struggle between Han/Ming and Manchu/Qing, rather than between rebel martial artists and the authorities themselves.

Itís the birthday of the God of Chivalry (I believe weíre meant to read that as referring to Guan Yu, a third-century general who was deified by imperial decree 400 or so years after his death), and all the kung fu schools in some Southern Chinese town have sent representatives to his temple to celebrate. Traditionally, the observances have been led by Master Lin Zan-Tin (Lu Ti, from Disciples of Shaolin and Shaolin Deadly Kicks), recognized as the official successor to the Shaolin abbots of yore, but Lin retired to a life of hermitage during the preceding year, and he has therefore sent some of his most talented pupils to take his place. That doesnít sit well with Master Wu Chung-Ping (Chiang Tao, of Men from the Monastery and Challenge of the Masters), sifu of a recently established Manchu martial arts academy supported by the Qing military governor (Lee Wan-Chung, from Come Drink with Me and Vengeance of the Vampire). Wu keeps rudely objecting to the newcomersí ďusurpationĒ of tradition, and although the priest of the temple (Sze-Ma Wah-Lung, of Bald-Headed Betty and Ghostly Vixen) tries his best to keep the peace, itís ultimately a lost cause. The inevitable fighting breaks out during the ceremonial display of prowess with the guandao (a glaive-like polearm which Guan Yu is traditionally credited with inventing), and Brother Law of the Shaolin delegation (Lau Kar-Wing, younger brother of action director Lau Kar-Leung, whose other film roles include Karate on the Bosporus and The Inheritor of Kung Fu) is killed in the brawl. The corrupt Qing gendarmes wonít do anything about it, of course, so thereís nothing else for it but a good, old-fashioned blood feud.

Normally, that would place the advantage with the Shaolin school, since Master Wu is a braggadocious putz, and his students are losers. But the aforementioned Qing general considers all martial artists to be troublemakers, so Wu is exactly the sort of person heíd prefer to have training them in his jurisdiction. Shaolin canít be allowed to win, and so the general sends outside the province for three Wu Tang masters to stack the deck. Their leader, Wang Jin-Ho (Tino Wong Cheung, from Drunken Master and The Battle Wizard), is bad enough news all by himself, but the real menaces are his two sidekicks, each of whom has turned himself into a veritable sideshow freak of kung fu. Ba Kang (Leung Kar-Yan, of The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers and Demon Strike) practices the discipline of Steel Armor, which, true to its name, renders his flesh impervious to attack. Traditionally, Steel Armor has one crucial weaknessó you canít armorize your cock and ballsó but Ba Kang has circumvented that problem by learning to retract his genitals behind the muscles of his body wall. Yu Pi (Johnny Wang Lung-Wei, from Five Shaolin Masters and Crippled Avengers), meanwhile, is a master of Qi Gong, which isolates, concentrates, and redirects the chi force of an enemyís blows back at him. Punch Yu Pi in the stomach, and all youíre going to accomplish is to dislocate your own shoulder. Needless to say, itís a fucking massacre when these guys arrive at Master Linís old school.

Speaking of Master Lin, his idea of hermitage is more sociable than most. He lives not only with his daughter, Zhen-Ziou (Irene Chen Yi-Ling, from The Jade-Faced Assassin and The Land of Many Perfumes), and his niece, Ah-Wai (Yuan Man-Tzu, of Evil Seducers and Infra-Man), but also with no fewer than four of his favorite pupils. One of the latter, Chen Bao-Rong (Chi Kuan-Chun, of Shaolin Temple and Yoga and the Kung Fu Girl), is dating Zhen-Ziou. Another, Li Yao (Alexander Fu Sheng, from Heroes Two and The Deadly Breaking Sword), is the object of Ah-Waiís amorous fixation, although he finds her at least as annoying as she is attractive. The other two guysó Mai Han (Bruce Tong Yim-Chaan, of The Duel and The Avenging Eagle) and He Zhen-Gang (Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, from Ghost Ballroom and The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, almost unrecognizable with a full head of hair)ó have no romantic entanglements, which might help explain why Lin turns to them first when survivors of the slaughter at the school swing by to report the bad news. Now it happens that the Shaolin Eagle Claw style had moves in its repertoire that would be just perfect for exploiting the weaknesses of Steel Armor and Qi Gong. Unfortunately, that style died out within the main line of Shaolin succession at some point since the destruction of the temple, so Lin himself canít teach it to anybody. Eagle Claw isnít lost completely, however, and Lin happens to know the sifu who has kept it alive in the present generation. Mai and He thus undertake a pilgrimage to the mountain retreat of the King of Eagle Claw (Chiang Nan, of Blood Reincarnation and The Boxer from Shantung) for training in the necessary techniques. The trouble is, weíve already seen that Ba Kang has closed the expected gap in Steel Armor, and while Yu Pi has no comparable categorical immunity to the finger strikes that normally defeat Qi Gong, heís considerably smarter than he looks. When Linís pupils square off against the Wu Tang assassins, Yu Pi tricks He into smashing his fingers to pulp against a massive hardwood pillar, then clobbers him at his leisure while Mai discovers to his horror that it takes more than a rolling crotch-kick to beat Ba Kang.

Even so, all is not lost. Lin still has Li and Chen, after all, and Wu Tang masters arenít the only ones who can play tricks with their kung fu. Whatís needed is a pair of attacks that the assassins wonít see coming, to forestall Ba Kang from retracting his junk at the crucial moment, and to overcome Yu Piís wariness about the finger strikes whose chi power he canít absorb. The Wing Chun style has a back-handed finger-flick of doom that a true master can deliver with lethal force using a windup of only two inches; if an opponent were to grapple with Yu Pi at close quarters, they could hit him with that absolutely without warning. And for Ba Kang, Lin prescribes an oldie-but-goodieó the very fakeout used to defeat long-ago Wu Tang arch-villain Bak Mei, the White-Browed Priest, who had upgraded his Steel Armor in the same way. Shaolin Martial Arts evidently assumes a version of the legend in which Bak Mei died in battle (some variants have him poisoned instead), and credits his unspecified killer with lulling him into a false sense of security by attacking him with Tiger Claw (useless against Steel Armor) before sucker-punching him with a Crane Peck strike to the eyeballs. A freshly-blinded man canít coordinate a timing-based defense, so if one of Linís students can replicate that Tiger-Crane switcheroo, itíll just be a matter of stomping Ba Kangís nads by whatever means opportunity presents. Again, though, Linís area of expertise does not include the necessary skills, so outside assistance will be needed. Chen Bao-Rong goes to study under Wing Chun master Yan Dong-Tian (Fung Ngai, from The Karate Killer and Enter the Kung Fu Dragon, playing a good guy for once), while Li Yao attempts to persuade the irascible Liang Hong (Beggar So himself, Simon Yuen Siu Tin, whoíd play much the same sort of role in Snake in the Eagleís Shadow and Master with Cracked Fingers) to teach him the Shaolin Tiger and Crane styles.

Whatís both interesting and disappointing about Shaolin Martial Arts is that itís an absolutely stereotypical kung fu movie. This is the first one of those that Iíve seen from Chang Cheh. What I mean is that itís the kind of film that plays out almost like a full-contact chess match, with heroes and villains alike maneuvering to exploit the specific, fiddly strengths and weaknesses of their own and each otherís particular styles of kung fu. The kind in which the good guys can be counted on to lose ignominiously at some point in the second act because the baddies reveal an unexpected skill or immunity, precipitating a quest for additional, torturous training in some canít-miss counter technique from a reclusive eccentric whom no sensible person would trust to walk their dog for them. The kind in which the conflict revolves almost entirely around abstruse rivalries between philosophically opposed martial arts schools, rather than practical matters like fighting against crime or oppression, seeking revenge on behalf of a wronged loved one, or clawing oneís way to the top of a crooked system. I donít mind that sort of movie, necessarily, but what Iíd found so appealing about Chang Chehís work in the genre thus far was that his films had more meaningful and intelligible stakes than whose pugilistic traditions would reign supreme in the province of Po Dunk. Still, thereís something to be said for seeing the maker of gritty, grounded movies like Vengeance! and The Boxer from Shantung take on so fanciful a premise as ďOh no! Heís so good at kung fu that his dick retracts!Ēó especially since it begins to suggest an answer to the question of where the fuck Five Element Ninjas came from.

At this point, I feel I should emphasize that Iím the sort of person who finds kung fu dick magic extremely hard to swallow, meaning that Iím absolutely not the target audience for Shaolin Martial Arts. Itís a tribute to the filmmakers, then, that I found this movie as enjoyable as I did, even without base-level buy-in to the very premise. In the end, though, I found the structure of the film to be the bigger challenge. It almost always feels awkward to me when a movie is set up so as to require emergency backup protagonists, but itís even worse when the film telegraphs that itís headed in that direction. In Shaolin Martial Arts, itís immediately obvious that the first pair of pupils whom Lin dispatches for further training are played by lower-billed actors, and have been less developed as characters, than the two who remain hanging around his homestead doing rom-com shit with the girls, and we know from the get-go that what theyíve been assigned to learn isnít going to help them against Ba Kang. The whole second act therefore feels kind of pointless, and only foreknowledge of the profound narrative weirdness that Hong Kong cinema sometimes engages in makes it possible to attempt giving a shit about Mai Han, He Zhen-Gang, or the King of Eagle Claw. (There is, after all, a non-zero chance that Chang and his recidivist co-writer, Ni Kuang, will find some excuse to bring them back from the dead to save the other two Shaolin heroesí bacon in the climactic fight.) And while I do appreciate being given a firmer idea of who Chen Bao-Rong and Li Yao are as characters, I wish the writers had come up with something more engaging than the aforementioned rom-com shit to develop them. All in all, itís not bad, but with the main line of Shaw Brothers Shaolin movies looming over it so closely, Shaolin Martial Arts really needed to try harder.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact