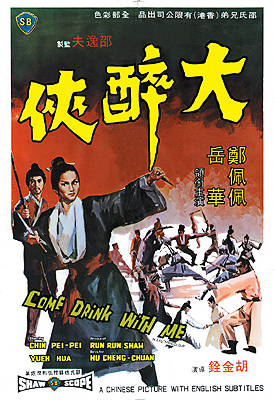

Come Drink with Me / Great Drunken Hero / Da Zui Xia (1966) ***

Come Drink with Me / Great Drunken Hero / Da Zui Xia (1966) ***

To the very casual fan, they’re all just kung fu movies. Somewhat less casual fans might draw distinctions based on the national origin of the relevant martial arts, granting that Enter the Dragon is a kung fu film, but insisting that The Street Fighter is a karate movie, Ong Bak a muay Thai movie, and Miami Connection a taekwondo movie. For the true connoisseur of Asian martial arts cinema, however, there are hairs that need splitting even among the films from a single territory, concerning the same family of fighting systems. If we’re talking specifically about Hong Kong fight flicks and their cousins from Taiwan and the Chinese mainland, then the categories of greatest concern are kung fu (obviously) and wuxia. The boundary between them is no more rigid or impermeable than that separating any other two closely related genres, and exceptions abound in both directions, but generally speaking, kung fu movies foreground unarmed combat, while wuxia revels in the entire arsenal of traditional Chinese melee weaponry. Kung fu movies tend to be set in the Qing era or later, while wuxia favors the more distant past. Wuxia has deeper roots in Chinese opera, to the extent that the oldest films of the type were often direct translations from one art form to the other— almost like pro-shot productions of Broadway or West End plays. Most importantly, wuxia tends toward an overtly fantastical portrayal of the martial arts, and isn’t much concerned with the details of their actual practice. Not only does the genre treat kung fu as magic, but it also treats it as basically fungible. If the hero is a swordsman of the Warring States period who can focus his chi to shoot fireballs from his hands, and it doesn’t matter in the slightest whether his fighting style is Taoist or Buddhist, internal or external, northern or southern, then you’re probably watching a wuxia film.

That’s all well and good, you might say, but what does wuxia actually mean? Literally, it’s “martial hero,” which points us toward one more important feature of the genre. Even more than kung fu movies, wuxia posits the notion of a Martial World— a semi-secret milieu of martial arts practitioners whose skills and mindset separate them from the concerns of ordinary life. Denizens of the Martial World might or might not have higher callings than the rest of us, but they certainly have other callings. To belong to the Martial World could mean taking on a commitment to roam the land righting wrongs, but it could also mean descending into deadly lifelong enmity against one’s closest friend over the inheritance of an old man’s walking stick. (And of course we’ve already seen how kung fu films employ the Martial World concept, with fighters at the highest level ever ready to wage war over even the most insignificant slight against their sifu or school.) You might think of the Martial World as a subculture freakishly devoted to honor, duty, and hierarchy, as imagined by a society that ascribed exaggerated importance to those things already.

Anyway, the emergence of wuxia as a cinematic genre was very nearly coeval with the emergence of a Chinese-language movie industry, but up until the mid-1960’s, wuxia on film looked very much like wuxia onstage. It makes sense, given what traditional subject matter we’re talking about, that the movies would treat it in a very traditional way. However, at the Shaw Brothers studio in particular, the years following World War II saw a burgeoning of both creative and technical ambition, as the eponymous family of producers increasingly sought to match the production values of films coming into Hong Kong from abroad. Musicals were the first beneficiaries of the drive to compete with foreign product, but Westernized approaches to filmmaking spread quickly enough to comedies, romances, historical dramas, and so forth. Finally, in 1966, wuxia got its turn to stretch beyond the conventions of the opera stage with King Hu’s Come Drink with Me. There was some irony in that, because it was a longstanding love of Chinese opera that made King want to try his hand at wuxia in the first place. In something of a parallel to the career of stage magician turned filmmaker Georges Méliès 60-odd years earlier, King understood himself to be using a young art form to preserve and pay tribute to a much older one, even as he transformed the latter into something breathtakingly new. Far from being stagebound and conventionalized, Come Drink with Me took full advantage of the Shaws’ giant Movietown studio complex on Clearwater Bay, with its permanent palace, temple, and village sets, and its ready access to undeveloped outdoor shooting locations. And rather surprisingly, at least for Westerners familiar with the purebred swordplay movies that would follow in its wake, Come Drink with Me owes quite a bit to the glossy musicals that were Shaw Brothers’ most profitable stock in trade at the time, casting as its heroes the stars of the recent smash hit The Monkey Goes West.

It’ll be a while before we meet that pair, however. Instead, Come Drink with Me devotes its attention early on to the bandit army led on a provisional basis by Jade-Faced Tiger (Chen Hung-Lieh, from The Iron Budddha and The Blind Swordsman’s Revenge). The brigands’ real leader (Wu Ho, of The 18 Bronzemen and The Killer Meteors) is imprisoned at the headquarters of the provincial governor just now, but Jade-Faced Tiger has a plan to get him freed. He and his men capture Master Chiang (Wong Chung, from Survival of a Dragon and A Tale of Ghost and Fox), the governor’s own son, with an eye toward an exchange of hostages. At first it looks like the bandits are on track to get what they want, for the governor dispatches his daughter, known as Golden Swallow (Cheng Pei-Pei, of The Shadow Whip and Princess Iron Fan), to negotiate with them. (In theory, Golden Swallow makes her entrance on the bandits’ turf disguised as a man, but the imposture wouldn’t fool Stevie Wonder.) The bargain the woman drives, however, is a stern one indeed: there will be no trade. Jade-Faced Tiger will release Master Chiang at once, and surrender with all his men into Golden Swallow’s custody, in return for which cooperation she promises them whatever passes for clemency in the law courts of the Ming Dynasty. And as she demonstrates during her first encounter with her adversaries, Golden Swallow has the fighting skill to take on the whole mangy lot singlehanded if it comes to that.

Obviously, then, Jade-Faced Tiger will have to rely on guile and treachery. The exceedingly forthright Golden Swallow is temperamentally ill-equipped to counter such tactics, so that would be a smart move even if she weren’t so formidable in a standup fight. Luckily for her, though (even if it takes her a while to see it that way), the governor’s daughter soon acquires an ally in the form of a boozehound beggar called Drunken Cat (Yueh Hua, from Shaolin Temple and Lady of Steel). The first time they cross paths directly, Drunken Cat makes a huge pest of himself by pilfering some rather important items from Golden Swallow’s room at the inn, and leading her on a merry chase across the city in order to get them back. But as she discovers upon returning to her lodgings, the night’s adventure actually saved her from a posse of Jade-Faced Tiger’s men, who dropped by to assassinate her in her bed only to find it empty. And although the beggar plays dumb when Golden Swallow tries to thank him the following morning, she eventually catches on that he and his panhandling battalion of singing orphans have encoded into the lyrics of their repertoire all the clues she needs to discover where the bandits are holding her brother.

Would you believe the criminals are holed up at the local temple? And would you believe they’ve been allowed to do so because the abbot there, Liao Kung (Yang Chi-Ching, from Vengeance! and Disciple of the 36th Chamber), is a kung fu master at least as wicked as Jade-Faced Tiger? Indeed, Liao Kung was a disciple of the same sifu who taught Drunken Cat the surprising skills that he displayed while keeping Golden Swallow too busy to bump off, which means that we’ve now got two intertwined plots to follow. While Golden Swallow works to rescue her brother and to bring Jade-Faced Tiger to justice, Drunken Cat and the abbot will gradually goad each other toward a life-or-death showdown over a seemingly ordinary bamboo staff that once belonged to their master. And incredibly, it’s difficult to say which of those is the A-plot, and which is the B-plot!

Come Drink with Me is the oldest martial arts film that I’ve seen so far, and having now followed the evolution of Hong Kong’s kung fu movies from the emergence of the bashers in 1970 through several successive cycles of development, it’s interesting to go back and see what the first modern wuxia picture doesn’t do. Most conspicuously, Come Drink with Me takes a startlingly primitive approach to its fight scenes. Cheng Pei-Pei and Yueh Hua were neither martial artists nor even acrobats, but singers and dancers. That left action director Han Ying-Chieh very little to work with, at least in comparison to what his successors of the 70’s and 80’s could count on from their performers, and he had recourse to a very different bag of tricks than what I’m used to seeing. Cheng’s and Yueh’s moves in their fight scenes are mostly figments of editing— although Come Drink with Me sells that a great deal more convincingly than, say, Black Belt Jones does whenever it’s Gloria Hendry’s turn for a punch-up. Partly that’s because the editing in these sequences really is shockingly good, considering what it’s up against, but it’s also because Han seems to have thought seriously about how to turn the adversity of two leads who couldn’t fight into a back-handed virtue. It doesn’t always work, but sometimes the editing trickery manages to suggest that the reason why we can never directly see whatever’s supposed to be happening is because Golden Swallow, Drunken Cat, and Abbot Liao Kung are quicker than the human eye. And whatever else we might say about these kung fu-less dancers, they’re very good at holding their bodies in postures that make it look like they just did something truly spectacular while we were looking the other way. The final fight between Drunken Cat and the evil abbot, meanwhile, gets to cheat by invoking the two masters’ supernatural powers. They battle as much with gusts of wind and steam cast from hoses concealed up their sleeves as they do with fists, feet, and staffs.

The other surprising thing about this movie when viewed from the far side of Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-Leung, and the Yuen Clan is King Hu’s obvious recognition that he was working for the musical company, almost as if he’d been hired to make a wuxia picture for 1930’s MGM. Remember that even The Monkey Goes West, based on the 16th-century fantasy adventure novel, Journey to the West, featured as much singing and dancing as swordplay, placing it not too far in tone and concept from The Wizard of Oz. Nevertheless, I was not expecting Drunken Cat and his orphan mob to bring Come Drink with Me screeching to a halt at the start of the second act with a full-on number. (Also, it’s interesting to see what constituted a number in 1960’s Hong Kong, given both a native musical tradition that had been cranking along for millennia before Western music theory made its presence felt in the Sinosphere, and a language that lends itself to an entirely different style of singing.) Come Drink with Me was made, though, at a time when The Sound of Music was the highest-grossing film in the history of Hong Kong movie theaters, so it tracks that King would employ such a gambit, if only on a token basis. For that matter, knowing about Hong Kong audiences’ ravenous appetite for musicals somewhat recontextualizes the entire phenomenon of martial arts cinema. Sure, there are several obviously related art forms rooted centuries deep in China’s own culture, and all of them were obviously vital in shaping chopsocky as we know it, in one way or another. But maybe for the people actually buying movie tickets in the domestic market circa 1966, a rip-roaring kung fu fight was merely a dance number with unusually high in-story stakes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact