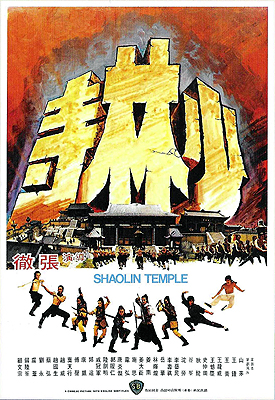

Shaolin Temple / Death Chamber / Shaolin Si / Siu Lam Ji (1976) **½

Shaolin Temple / Death Chamber / Shaolin Si / Siu Lam Ji (1976) **½

Does it seems strange to you that Chang Cheh made four whole movies about the legends of the Shaolin Temple, yet just barely had the temple itself figure in any of them? Because that definitely seems strange to me. With the fifth film in the series, though, Chang and his regular co-writer, Ni Kuang, went back at long last to tell the story of how Shaolin originally became a haven for rebellious martial artists, and a thorn in the side of the Qing Dynasty. Aptly enough, they called it Shaolin Temple. Finally, then, we get to see torturous and counterintuitive training regimens imposed on a systematized mass basis. We get to see pains in the ass of power like Fang Shih-Yu and Hu Te-Ti drilled into fighting form by whole teams of dour old monks. We get to see the temple’s burgeoning difficulties with the Qing authorities from the monks’ point of view for a change, offering some indication of why they’d take the fatal step of bringing even more heat down upon themselves by extending instruction in the fighting arts to any sufficiently promising troublemaker who kneels at their front door. It was way past time for all that stuff, so the only reason why I’m a little surprised to get it now is that Chang had put it off for so long in the first place. What I absolutely did not see coming, however, was the effect that institutionalizing the usual kung fu training sequences would have on the film as a whole. The last thing I ever expected of Shaolin Temple was that would feel so much like a boys-only Shaw Brothers take on The Belles of St. Trinian’s!

Fang Shih-Yu (Alexander Fu Sheng once again), Hu Hui-Chien (still Chi Kuan-Chun), and Hung Hsi-Kwan (surprisingly not Chen Kuan-Tai, but rather Frankie Wei Hung, of Oriental Playgirls and The Shaolin Boxers) have been kneeling outside the main gate to the Shaolin Temple for five days, beseeching admission. The three youths have heard tell of the powerful kung fu secrets which the monks preserve, and they believe those secrets to be the keys that will enable them to succeed in their own personal vengeance-quests. The monks find this vigil disconcerting, especially Master Hui Xian (Shan Mao, from One-Armed Boxer and The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers). Sure, kung fu is an important part of the temple’s discipline, but it’s something the adepts teach to novice monks, not to angry kids with axes to grind. Abbot Fang Wen (Ku Wen-Chung, from Five Fingers of Death and The Sentimental Swordsman) has been meditating on the matter since the supplicants arrived, and has even sought the advice of Abbess Wu Mei (strange that I can’t pin down who played this rather important character). The abbess has something of a personal connection to the trio on the doorstep, you see, because she taught Fang Shih-Yu’s mother how to fight many, many years ago. As the downpouring rain that was making the would-be students’ vigil even more miserable comes to an end, Fang Wen finally reaches a decision. The Qing emperor has issued an edict outlawing all teaching of the martial arts. It’s only a matter of time before that ban is extended to monks using kung fu as an advanced meditation technique, and when that happens, it’s all over for the centuries-old martial traditions of Shaolin. But if the monks disseminate their kung fu practices outside the monastery, then it becomes altogether harder for the Qing to stamp them out. Besides, who knows? Maybe some of those truculent little bastards clamoring to learn the Snake Fist and Tiger Claw will have what it takes to send the Qing packing back to Manchuria once they’ve been properly trained. Fang Shih-Yu and the others can come on inside and begin their studies.

Meanwhile, a small boat carrying six armed and armored men comes ashore not far away. The passengers are Hu Te-Ti, Tsai Te-Chung, Ma Fu-Yi, Fang Ta-Hung, Ma Chao-Hsing, and Li Shih-Kai, all of whom we already know from Five Shaolin Masters. (The first three are played by the same actors, too: David Chiang Da-Wei, Ti Lung, and Johnny Wang Lung-Wei. The others have been recast, though, because the actors who played them before have different roles in Shaolin Temple. Fa Ta-Hung is now Wang Chung, from The Hammer of God and The Deadly Duo. Ma Chao-Hsing is now Law Wing, from Pursuit of Vengeance and The Seven Coffins. And Li Shih-Kai is now Yueh Hua, of Come Drink with Me and The Monkey Goes West.) They’re the last survivors of the army of Zheng Cheng-Gong, a Ming Dynasty loyalist who had hoped to combine his forces with those of a planned invasion of fellow patriots from Taiwan. Obviously there’s no prospect of that now, but Hu figures he and his fellows might still be able to support the invasion by seeding the southern provinces with guerilla cells to rise up against the Manchu when the armies from Formosa land. To do that right, however, they’ll need a secure base of operations. Fortunately, they’re met on the beach by Yan Yong-Chun (Shih Szu, from A Deadly Secret and The Crimson Charm), a longtime friend of Tsai’s who happens to have studied kung fu under Wu Mei. (You might have heard of Yan Yong-Chun under the Cantonese reading of her name, Yim Wing-Chun. Yim is the legendary propagator of the kung fu style that bears her given name, which Wu Mei— or Ng Mui in Cantonese— is supposed to have devised specifically for her.) She takes the rebels to the Shaolin Temple, where Hu and Tsai once pulled stints as apprentice monks before leaving to go into the revolution business. With that preexisting tie to the temple, Hu and the gang are able to sidestep the kneeling ordeal that has become Shaolin’s equivalent to the SATs.

Speaking of kneeling on the front porch, though, the rather large group that was already doing that gets distinctly miffed to see the Zheng army survivors being allowed to jump the turnstile. That causes a fair many defections among their number, followed by two more waves when the monks come out to tempt the supplicants with food and water. Still others give up out of sheer discouragement, until eventually only three remain: Zhu Dao (Bruce Tong Yim-Chaan, from The Big Brawl and The Water Margin), Lin Guang-Yao (Phillip Kwok Chun-Fung, of Crippled Avengers and Demon of the Lute), and Huang Song-Han (Lee Yi-Min, from World of the Drunken Master and Manhunt). This bunch meet at last with the monks’ approval, and are allowed into the temple to join the slowly but steadily growing cohort of lay disciples.

Much to the six youngsters’ consternation, however, only Hu Hui-Chien (who already picked up a smattering of the Five Animals and Five Elements techniques on his own before coming to the temple) seems at first to be getting any proper training in kung fu. Fang Shih-Yu, for example, finds himself stoking the cooking fires in the kitchen. Huang Song-Han, also on kitchen detail, spends his days literally chained to the ceiling, in a harness contraption that enables him to keep several industrial-sized woks of rice porridge stirred at once with a seven-foot pole. Zhu Dao is put to work in the library, doing something that I’d have to know a lot more than I do about how Chinese books were traditionally made even to attempt explaining. And although Lin Guang-Yao at least gets earmarked for gymnastics training, all that means in practice is day after endless day of jumping up and down at the bottom of a great, big hole with ever-heavier sets of iron cuffs strapped to his legs. (Weirdly, we never see Hung Hsi-Kwan at all during this phase of the film. Maybe we’re supposed to assume, given his reputation as the greatest of the lay disciples of Shaolin, that he was always above this sort of thing?)

We all know where this is going, though, right? Hidden away in all these menial chores are the physical rudiments of various Shaolin fighting styles. Fang’s log-splitting is giving him the grip strength required by the Tiger style. Huang’s wok-stirring, unbeknownst to him, has been training him all this time to fight with the bo staff. When Lin’s leg-weights come off, he’ll be able to leap tall pagodas in a single bound. And Zhu is developing nigh superhuman balance and unbelievably tough feet. But Fang remains impatient to start learning real fighting techniques, even after he gets wise to the monks’ game. He therefore starts burning the midnight oil, mimicking the motions of a mysterious masked monk who likes to work out in a chamber visible from the temple’s inner courtyard after his brothers have all gone to bed. And then once a month or so, Fang puts his surreptitiously acquired skills to the test by barging in on the altogether more serious training sessions of the Zheng Army fighters, and annoying the short-tempered Ma Fu-Yi into beating his ass.

Fang Shih-Yu isn’t the only one at the temple engaged in subterfuge, however. On the benign side, Wu Mei has enlisted Hu Te-Ti and Tsai Te-Chung to act as her agents during the coming “calamitous times” foreseen by the abbot. Thus she begins tutoring the pair one-on-one— Hu in the use of the chain whip and three-section staff, and Tsai in a new unarmed style optimized for fighting at close quarters against a stronger opponent. Wu Mei also places Tsai under a vow to pass her teachings along to Yan Yong-Chun specifically after he leaves the temple. But then on the pro-calamity side, Master Hui Xian turns out to be playing for both teams, reporting regularly on the doings at Shaolin to a coterie of Manchu generals led by King Man-Gui (Ku Feng, from The Five Deadly Venoms and Bat Without Wings). Worse yet, the double-dealing monk suborns Ma Fu-Yi to be his cat’s paw among the Zheng Army contingent, exploiting Ma’s growing dissatisfaction with the life of a revolutionary partisan. The various schemes are all catapulted into action when Fang Shih-Yu, having judged that he has acquired everything he needs to prosecute his private vendetta successfully, forces his way into Wooden Man Alley, the maze of increasingly deadly sparring machines that serves as the Shaolin Temple’s final exam.

Chang Cheh has revealed himself to be many things since I began dabbling my way through his filmography, but up to now, I’d seen nothing to indicate that he possessed more than the most vestigial sense of humor. Yet although it would be exaggerating to call Shaolin Temple a comedy, the fact remains that it portrays most of the younger lay disciples as goofball misfits, even despite the conceit that these guys are the serious, dedicated ones among the crowds of supplicants whom the monks mostly turn away. The humbling miseries to which they’re subjected during the initial phase of their training are consistently played for laughs, complete with “whomp-whomp” music when, for example, Lin Guang-Yao brags to his fellows that he’s “almost” mastered gymnastics, only to stagger in at the next change of scene with twice as much scrap iron weighing down his legs. Similarly, all the kids save Hu Hui-Chien and the mostly absent Hung Hsi-Kwan start off displaying endless ingenuity in the field of shirking the tasks assigned to them, again with generally humorous results. And because these antics occur in a school setting, it’s irresistibly tempting to view Shaolin Temple’s second act through the lens of both earlier and later comedies about misbehaving college and boarding-school students. Fang Shih-Yu talking up the seemingly pointless indignities of the temple kitchen immediately upon meeting Huang, Lin, and Zhu becomes the traditional psyching-out of the new underclassmen, while his monthly duels with Ma Fu-Yi take on shades of Bluto’s repeated clashes with Neidermeyer in Animal House. It’s very strange seeing that sort of low-stakes conflict slotted into the middle of a film that begins with portents of a threefold vengeance-quest and a Shaolin-Wu Tang war, and ends with the bloodiest, most prolonged destruction of the Shaolin Temple that we’ve seen yet. The mingling of contrary sensibilities mostly works, however, and I found the young fighters’ course of instruction to be the most consistently enjoyable part of the film.

Conversely, it would have benefited Shaolin Temple considerably if Chang had prolonged the climactic siege of the monastery a little bit less. The trouble, fundamentally, is that we already know more or less how this huge, sprawling fight is destined to end. We know ahead of time which heroes have to survive in order to fulfill their obligations to other parts of the broader story (although there are a few surprises regarding which villains do and do not live to wreak havoc another day), and we know that Shaolin is doomed despite all their best efforts. In that context, the blow-by-blow of the individual duels just isn’t interesting enough to support the in-depth treatment that Chang gives it here, especially with eleven major heroes each demanding a turn in the spotlight. Indeed, a better idea still might have been to forego the destruction of the temple altogether (after all, we’ve seen three different versions of it from Chang already), and to treat the showdown against the traitor-monks in Wooden Man Alley as the climax instead. That material is all-new, not only in the sense of having not yet figured in any of Chang’s Shaolin Temple movies, but more importantly insofar as the Wooden Men themselves add an unprecedented complication to the spectacle of heroes battling villains. Furthermore, Fang’s premature foray into Wooden Man Alley makes for a fitting and satisfying third act, while the Qing generals’ attack on the temple requires adding a clunky and unnatural-feeling fourth. The series as a whole has been remarkably accepting of loose ends and lacunae, so it would have been no big deal to leave General King and his followers still looming ominously in the background at the final freeze-frame.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact