Five Fingers of Death / King Boxer / Hand of Death / Invincible Boxer / Tian Xia Di Yi Quan (1972/1973) **Ĺ

Five Fingers of Death / King Boxer / Hand of Death / Invincible Boxer / Tian Xia Di Yi Quan (1972/1973) **Ĺ

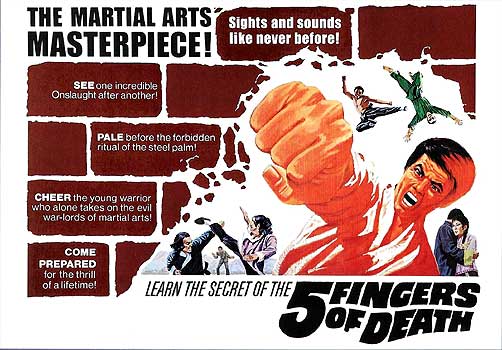

It makes perfect sense that Hong Kong kung fu movies, having modernized themselves at the turn of the 70ís along similar lines to the transformation of wuxia films that followed Come Drink with Me several years earlier, would take the other nations of the western Pacific Rim by storm. After all, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Indonesia, and the Philippines each had their own martial arts traditions, so their audiences and filmmakers alike were primed to respond to the likes of Vengeance! and The Hammer of God. The chopsocky craze of the 70ís was truly global in scope, however, which cries out for considerably more explanation. I canít adequately address that mystery in a single review, or course, even if I felt significantly surer of my grasp of the topic than I do. But a review of Five Fingers of Death is the natural place to begin grappling with it, because this was the first martial arts movie from Hong Kong to secure release in the United States, and its unexpected profitability for Warner Brothers provided the impetus for many, many more kung fu movies to make their way across the Pacific to American theaters over the ensuing decade or so.

Like any sufficiently established kung fu master, Sung Wu-Yang (Ku Wen-Chung, from Shaolin Temple and Sexy Girls of Denmark) has enemies, and a pack of them led by the bald and bulgy-eyed Wan Hung-Chieh (Chan Shen, of Five Element Ninjas and Haunted Tales) is out hunting for him even now. Although Sung is still a formidable fighter, advancing age has taken the spark from his lightning-like reflexes, and Wanís ruffians give him a harder time than he likes to admit. Fortunately, the old manís favorite pupil, Chao Chi-Hao (Lo Lieh, from The Hammer of God and Black Magic), quickly arrives on the scene to back him up. Wan and his men sensibly take to their heels at that point.

Tonight was supposed to be a joyous occasion at the Sung house, because the sifuís other top student, Lu Ta-Ming (Jin Bong-Jin, of Evil Under the Sun and Public Cemetery), is due to return from a long course of supplementary instruction from Sungís ally, Master Suen Hsin-Pei (Fang Mian, from Mantis Fist Fighter and Exorcising Sword). Sungís performance in the fight just now has cast a pall over the evening, though. It gets him thinking that he might have done Chao a disservice by not sending him to train under the other sifu, too. Suen is a somewhat younger and spryer man, so it stands to reason that an up-and-coming martial artist could learn more from him. Chi-Hao is reluctant at first to make the journey, because heís in love with Sungís daughter, Ying-Ying (Wang Ping, of Vengeance! and Killer from Above). However, the prospect of representing the old masterís kung fu lineage at a forthcoming championship tournament puts the trip to Suenís school in a new light. Romance is one thing, but this is honor weíre talking about now!

Speaking of kung fu contests, a much less formal, but no less significant one unfolds in the town square the next day. A Mongolian giant who calls himself Hercules Bataar (Bolo Yeung Sze, from Enter the Dragon and The Deadly Duoó merely massive here in his youth, in contrast to the squat, hulking cube of muscle heíd become later on) has set up on a street corner with a barker (Tsang Cho-Lam, who played similar tiny parts in Virgins of the Seven Seas and The Girlie Bar) challenging all comers to pit their fighting prowess against his, for an ante of five dollars per bout against a hundred-dollar prize purse. Stronger than an ox and seemingly impervious to pain, Bataar looks unbeatable until a stranger by the name of Chen Lang (Kim Ki-Joo, of Kung Fu Fever and The Ghost Lovers) puts up his five bucks. Although he obviously canít match Bataar for sheer power, Chen is much quicker, and his dome-like forehead is even more invulnerable than the Mongolís. The fight ends with Chen simply head-butting Bataar down to the pavement.

But before he can walk off with the prize money, Chen is accosted by an arrogant bastard named Meng Tien-Hsiung (Tung Lin, from The Oily Maniac and The Water Margin), apparently a higher-ranking associate of our old pal, Wan, albeit not directly his boss. Meng tells Chen that now he has to fight him to claim his winnings from Bataar, and the first tentative flurry of punches suggests that this will be a much more even match. (Still, I canít help thinking that Chenís bulletproof noggin gives him the edge once again.) Before the duel can proceed any further, however, Mengís father, kung fu master and gang oligarch Meng Tung-Shun (Tien Feng, from Temple of the Red Lotus and Chinese Connection), intervenes to break it up. Gangster or not, the elder Meng didnít bring up his son to engage in such crude dickery, and he offers Chen both a profusion of apologies and the penitential hospitality of his palace for the evening. He also offers Chen a job, being a significantly better judge of badasses than his idiot kid.

But returning now to Chao Chi-Hao and his extended martial arts training, he has occasion en route to Master Suenís place to save itinerant singer Yen Chu-Hung (Wong Gam-Fung, of Adultery Chinese Style and The 14 Amazons) from still another band of ruffians. No, waitó thatís the same band of ruffians yet again! By now itís apparent that these guys are Meng Tung-Shunís minions, and even this will not be the last time that Chao tangles with someone in the crooked sifuís employ. Thatís because Meng means to enter his son in the very same tournament for which Sung is grooming Chao, and while Meng Jr. is a fairly skilled fighter, his old man knows perfectly well that he isnít that good. For Tien-Hsiung to become champion of Northern Chinese kung fu, winning the associated prestige for his fatherís mob, it will be necessary to winnow the field first, so that only the B-minus students and below are in competition. That will mean keeping fighters trained by Sung Wu-Yang and Suen Hsin-Pei alike out of the contest, let alone anyone (like Chao Chi-Hao or Lu Ta-Ming, for example) who has studied under both masters. Wan and his bully-boys are obviously not up to the task of cowing two whole kung fu schools, nor can Meng Sr. risk his son getting busted up before the tournament, but thatís where Chen Lang and his Krupp-steel head come in. And if even Chenís unique talents wonít suffice, then wily old Meng still has two more cards in his hand. First, heís hired a trio of Japanese mercenaries under the leadership of a karate and longsword master called Okada (Chao Hsiung, of Iron-Fisted Monk and Come Drink with Me), on the theory that Sungís and Suenís kung fu will have no counter to the unfamiliar fighting arts of Fuso. And second, Meng is just the kind of treacherous motherfucker to exploit rifts among his enemies, like the one that opens up between Chao and Suenís right-hand man, Han Lung (James Nam Seok-Hoon, from The Ill Wind and Lady with a Sword), when the sifu chooses the new kid in school to inherit the closely guarded secret of the Iron Palm.

At least from an American point of view, the obvious question to ask about Five Fingers of Death is, ďWhy this one?Ē Given the scads of martial arts movies made in Hong Kong since the watershed year of 1966, what was it about King Boxer that made somebody at Warner Brothers think that with a new title and the right advertising campaign, it could be a big enough hit to be worth importing? And why were they so right in the end that Five Fingers of Death would become the beachhead for a full-scale Hong Kong invasion of the US grindhouse market, and the flashpoint for a decade-long pop-culture craze? I mean, itís a decent film, but it hardly seems worth getting wildly excited about. Lo Lieh, although reasonably charming, lacks the charisma of a Jimmy Wang Yu or a David Chiang Da-Wei, let alone a Bruce Lee or an Alexander Fu Sheng. The fight scenes are competently staged and effectively paced, but theyíre limited by the stiff-armed flailing common to the ďbasherĒ stage of fu-film development. Action director Lau Kar-Wing displays nothing like the breathtaking talent and technique that his brother, Lau Kar-Leung, would bring to the Shaw Brothers Shaolin cycle just a couple years later. And apart from Kim Ki-Joo as Chen Lang, the villains in this movie are all faintly disappointing, offering memorable characterizations or impressive physical performances, but not both.

I think what it comes down to is that Five Fingers of Death was simply more digestible than other movies of its time and type. Gangsters trying to rig a championship fight are a premise that requires no familiarity with Chinese culture or historyó to the point that Iím not even sure the title change from King Boxer was really necessary. Thereís no Ming-vs.-Qing to keep track of in this film, nor any Han-vs.-Manchu, Shaolin-vs.-Wu Tang, or even North-vs.-South. Five Fingers of Death doesnít expect you to know a thing about the Martial World or the Warring States or the Boxer Rebellion or the Opium Wars. And crucially, the only mention of particular kung fu styles or techniques arises when Chao begins training in the Iron Palm, which is portrayed less as a physical discipline than as a kind of magic. Chaoís hands literally glow red when he uses it, but thereís no change visible in his fighting styleó not least because he hasnít really got one of those in the first place. Compare that to the treatment of high-level kung fu skills in Chang Chehís Shaolin movies, in which an attentive eye quickly learns to distinguish Crane from Mantis from Tiger from Leopard, or Drunken Master, in which itís obvious at once even to the totally uninitiated that nobody alive could throw a kick like Hwang Jiang Lee. It might also have aided American comprehension that Master Mengís Japanese assassins shoulder an ever-increasing share of the villainy in Five Fingers of Death. The moment Okada clomps onto the screen on his geta clog-sandals, sporting a short but voluminous black robe and a katana on his hip, an American viewer in 1973 could respond, ďOh, I get it. Heís just like the bad guys in Yojimbo or The Seven Samurai.Ē All in all, Five Fingers of Death falls into the sweet spot of being just unfamiliar enough to seem exciting, but not foreign enough in its subject matter or sensibilities to baffle a novice audience. It would make for a pretty good set of chopsocky training wheels even today, although viewers already acquainted with more highly evolved examples of the form are likely to find it somewhat wanting.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact