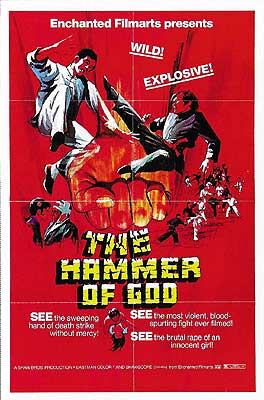

The Hammer of God / The Chinese Boxer / Long Hu Dou (1970/1973) ***½

The Hammer of God / The Chinese Boxer / Long Hu Dou (1970/1973) ***½

Jimmy Wang Yu was the first real star to emerge from Hong Kong martial arts cinema following its post-1966 modernization. Wang started on the wuxia side of the somewhat porous wuxia/kung fu divide, but he eventually worked in both modes, not only as an actor, but as a writer and a director as well. The Hammer of God, also known to English-speaking audiences outside the United States as The Chinese Boxer, was Wang’s first kung fu film. It was also his first script, and his first time in the director’s chair. Made later the same year as Chang Cheh’s Vengeance!, it completes the transformation that movie started by bringing the new, purely cinematic filmmaking style pioneered in late-60’s wuxia to a picture focused on strictly bare-handed fighting. It was a hugely influential production, establishing a variety of tropes and patterns that the genre as a whole would follow until its eclipse in Hong Kong by stunt- and gunplay-centric action movies a decade and a half later.

Diao-Erh (Chiao Hsiung, from Five Fingers of Death and The Golden Lion) has a grudge. Years ago, he was banished from the Zhongyi kung fu school by sifu Li Chun-Hoi (Fang Mian, of The Iron Buddha and Return of the Dead), who considered Diao-Erh’s violent, vengeful character to be incompatible with the spiritual aspects of his teachings; the fighting skills at Li’s command were too powerful to be entrusted to such a cruel hothead. Diao-Erh emigrated to Japan, where he mastered the art of judo, and now, at long last, he is on his way to Li’s school to give his former master what-for. That doesn’t go quite the way Diao-Erh envisioned. Although his foreign fighting arts put him well ahead of Li’s current crop of students, the sifu himself knows tricks fit to render a far more formidable judoka than Diao-Erh almost totally impotent. Nevertheless, being a man of peace at heart, Li stops short of killing his revenge-mad former pupil. That might not be the smartest thing to do, however, for Diao-Erh makes his retreat with a vow to return in a month’s time, accompanied by Japanese fighters trained not in judo, but in karate.

Master Li is serenely untroubled by Diao-Erh’s threat. True, karate may be deadlier on a blow-for-blow basis than his own kung fu, but he is confident that it can be defeated by a combination of Light Leaping and the Iron Palm— techniques which Li himself practices, although he has not seen fit to impart them even to his two star pupils, Lei Ming (Jimmy Wang Yu, from One-Armed Swordsman and One-Armed Boxer, playing a character with the regulation number of arms for a change) and Cheung Da-Lung (Cheng Lei, of Heads for Sale and The Heroic Ones). The sifu’s certainty is not shared, however, by his daughter, Li Siao-Ying (Wang Ping, from Magnificent Bodyguards and Vengeance!). She has a terrible feeling about the looming rematch, but can’t convince anybody to take her fears seriously. And that’s unfortunate, because Siao-Ying has the right of it. At the end of the month, Diao-Erh comes calling with no fewer than three of the promised karate masters, and looks on gloating while Kitashima (Lo Lieh, from Web of Death and The Girl with the Thunderbolt Kick), Tanaka (Wang Chung— no, really— of The Water Margin and All Men Are Brothers), and Ishihara (Chan Sing, of Fearless Kung Fu Elements and The Beasts) slaughter Master Li together with all his students. In the aftermath, Diao-Erh seizes control of the Zhongyi School property, and converts it into a patently crooked gambling den.

But wait! Diao-Erh and his imported hit men weren’t quite as thorough as they thought. Lei Ming, although beaten within an inch of his life, still had that one last inch to go when Li’s enemies withdrew to celebrate their victory, and Siao-Ying was able to drag him away to safety before they came back to dispose of the bodies. It takes her months to nurse him back to health— months spent living in secret, in the worst slum in town— but as soon as he’s feeling his old self again, Lei sets about training for a campaign of vengeance. Remembering Master Li’s pronouncement about Light Leaping and the Iron Palm, Lei dedicates himself to acquiring both skills. (He does this without recourse to a new sifu, curiously enough, so maybe we’re supposed to take it that the principles behind the techniques are widely known, even if their actual practice is less so?) Then, once he can leap as lightly and palm as ferrously as any boxer in China, Lei dons what looks disorientingly like an N95 mask, and begins making a nuisance of himself for all the criminal enterprises that Diao-Erh has launched in the months since he eliminated what he thought was the only source of credible opposition. Again Diao-Erh tries to counter by importing hired muscle from Japan— this time a pair of ronin called Kume (Wong Ching, from Night of the Assassins and Heroes Two) and Rumura (Tung Li, of Snake-Crane Secret and The Evil Snake Girl)— but Lei goes through them like a crane-peck punch through a paper fan. Diao-Erh and his karate killers will just have to handle this fight themselves.

I was stunned to learn that Jimmy Wang Yu had never written or directed a movie before The Hammer of God. Although I still consider myself very much a novice with regard to Hong Kong exploitation cinema generally, and kung fu films in particular, I’ve seen enough by now to have certain expectations going into one of these things. Foremost among those is that narrative construction is going to follow decidedly foreign assumptions with regard to pacing, flow, linearity, character focus, tone, and so on. I brace myself for starting and stopping points in peculiar places, frequent and unpredictable shifts in viewpoint, jokes where no Western screenwriter would ever consider putting them, sudden outbursts of sentimentality in the midst of fantastical ultraviolence, you name it. But The Hammer of God isn’t like that at all. From the massacre of the Zhongyi students that closes out the first act, it drives straight on toward the showdown between Lei Ming and the gangsters as relentlessly and singlemindedly as Lei himself. Here in his very first produced screenplay, Wang found the perfect minimum of story and character development necessary for us to understand the motivation, the stakes, and the cost of the conflict. With just a scene or two for each, he establishes Diao-Erh’s festering resentment, and the wisdom of Li Chun-Hoi’s long-ago verdict against him; Li Siao-Ling’s devotion to Lei Ming, and her premonition of doom for her father and his pupils; and most of all, Lei Ming’s transformation from carefree youth to remorseless engine of vengeance. Also, in stark contrast to Chang Cheh’s movies on similar themes, Wang conveys in no uncertain terms that in this story, the destruction of Diao-Erh and his followers might satisfy honor, but it won’t satisfy Ming or Siao-Ling. Much like in Coffy or Mad Max, The Hammer of God denies the possibility of a happy ending, regardless of who comes out on top in the final fight.

The ruthless efficiency of Wang’s script leaves The Hammer of God in need of ways to fill time, and Wang met that challenge by building up a mood of almost excruciating tension before each of the action set-pieces. As director, he comes across as something like the missing link between Sergio Leone and John Woo, doing for fisticuffs what those two did for gunplay. Wang also gives one brief nod to his wuxia roots during the battle against the ronin by having Lei help himself to one defeated opponent’s sword before pressing his attack against the other. The most surprising sequence of suspense exploding into action, however, contains no fighting at all. It has Lei, in his N95 Avenger getup, sneaking into the former Zhongyi school while Diao-Erh’s men are sleeping in order to soak the place thoroughly with kerosene and set it alight; the gangsters all have more pressing concerns upon awakening than to engage the masked arsonist in a punch-up! Nothing else communicates so clearly what Lei has allowed himself to become in the name of settling the score for his murdered sifu and comrades.

Of course, most of the action in The Hammer of God is all about fighting— and since that’s going to be the main source of appeal for most viewers, I should probably say something about it. Simply put, the combat in this movie is odd. Although The Hammer of God is generally counted among the bashers— is indeed often cited as the original basher, even— it’s noticeably more sophisticated than most of that lot with regard to its fight choreography and action staging. In some ways, it even looks ahead all the way to the wire-fu era of the late 90’s and early aughts, although there’s certainly an argument to be made that that counts as a strike against it. Of the principal combatants, only the karate-trained Chan Sing had any serious martial arts background. Nevertheless, Jimmy Wang Yu had years of experience in stage fighting, and by 1970, he was expert indeed in tricking the camera. Whatever the reality of the situation, Wang looks like a martial artist here. Furthermore, he looks like a martial artist of a significantly different tradition from his opponents, using his own distinct defensive stances, fist configurations, and patterns of maneuver. As for the supposed karate fighters, their art is distinguished in The Hammer of God by a pronounced reliance on trampoline-assisted jumps and wire-dependent flying kicks— which is interesting, because that’s more or less how I recall karate being depicted at the time in Western media made by people who wouldn’t know a black belt from a Miss Teen U.S.A. contestant’s sash.

But what makes The Hammer of God stand out most from the rest of the fu-film pack is the interaction between Wang’s direction and the cinematography by Hua Shan. We’ve seen Hua before around here, as the director of Infra-Man— and dearly though I love that movie, I can’t justly accuse it of being well directed. Evidently that was a case of rising to the level of one’s incompetence, however, because The Hammer of God reveals Hua as a cameraman of exceptional ability. It does so right up front, too, starting with a series of closeups on non-identifying parts of Diao-Erh’s body that track his movements across town as he stalks toward the Zhongyi school. By the time he reaches his destination, you’re sure to be on tenterhooks wondering who this guy is and what he’s up to. Then throughout the film, Hua is indispensable as the instrument through which Wang plays the Leone/Woo “ballet of violence” tune. Consider, for example, the juxtaposition of the inferno at the casino and the battle against the ronin which follows it, the latter set in a snow-swept thicket of obscuring head-high grass. Each scene is impressive enough in itself, but playing them against each other like this— orange vs. white, fire vs. ice, raw panic vs. clockwork discipline— is simply brilliant. A similar use of imagery to deepen the narrative information in a scene occurs during the final fight between Lei Ming and Kitashima. As the duel wears on, both belligerents seem to rely less on their mastery of the fighting arts and more on the mere savagery of their mutual hatred. And as that devolution plays out, they both become literally dirtier to match the tenor of their combat: their clothes torn, their bodies caked in dust and mud, soaking in their own and each other’s blood. Meanwhile, Hua’s camera comes closer and closer, until whatever technique the foes are still bothering to apply is all but invisible anyway. We see that these are no longer martial artists, and barely even men fighting over human concerns like honor, revenge, or material gain; they’ve reduced themselves and each other to animals struggling to survive, and to make sure that the other animal doesn’t. My favorite shot in the whole film, though, comes at the climax to the Zhongyi massacre. As the melee becomes general in the wake of Master Li’s death, the camera dollies out to show the entire main hall of the school, subtly overlit to catch each puff of coughed-up blood as the Zhongyi students go down, their lungs crushed by the awesome power of the Japanese mercenaries’ fists. The futility of the students’ resistance becomes clear in that moment, in a way that not even the vanquishing of their sifu put across. I never would have guessed that Hua had anything remotely like this in him, but I’ll be regarding his presence behind the camera (if perhaps not necessarily in the director’s chair) as a selling point going forward.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact