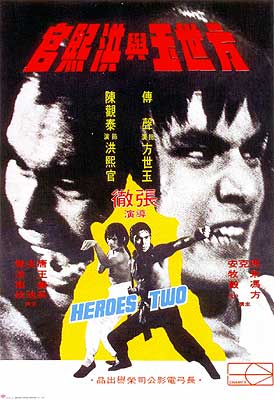

Heroes Two / Bloody Fists / Blood Brothers / Kung Fu Invaders / Temple of the Dragon / Fang Shi Yu yu Hong Xiguan (1974) ***

Heroes Two / Bloody Fists / Blood Brothers / Kung Fu Invaders / Temple of the Dragon / Fang Shi Yu yu Hong Xiguan (1974) ***

The Shaolin Temple is a bit like the Wild West. On the one hand, itís a real place, where generations of real people lived and worked, tied thereby to all the other important but unexciting realities that living and working inevitably entail. At the same time, though, itís also a locus of myth, where historical figures and events are apt to be swallowed up by the legends adhering to them, which come to mean far more to posterity than anything as prosaic as what actually happened. Factually speaking, the Shaolin Temple is a monastery at the foot of Wuru Peak, in Central Chinaís Henan province, which has undergone numerous reversals of fortune and cycles of official favor and disfavor over the course of its long history. For centuries, it has been the paramount spiritual home of Chan Buddhism (better known in the US by its Japanese name, Zen Buddhism), a major center of religious learning, and a nexus from which Indian scriptures, translated into Chinese, were disseminated across the Sinosphere. In the late 90ís and early 2000ís, it was also a tourist trap of embarrassing proportions, and today, itís a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Legendarily, though, the Shaolin Temple is the cradle of Southern Chinese kung fu, a rallying point for resistance against oppression, and a symbol of indomitable fighting spirit.

For that, we can (again, legendarily) thank one of the prominent Indian monks who established themselves at the Shaolin Temple during its first two centuries of operationó although the legends donít always agree on which one. But whether you want to credit Buddhabhadra, the founder of the temple, or Bodhidharma, the first Patriarch of Chan Buddhism, somebody in those days got the bright idea that the monks should discipline their bodies as well as their minds, and instituted training in the martial arts to supplement more conventional forms of meditation. For our purposes, though, those primordial developments are less important than what supposedly happened eleven or twelve centuries later, after the Han Chinese Ming Dynasty was overthrown by the Manchu Qing Dynasty. By that point, or so the stories have it, the original Shaolin Temple in Henan had been supplemented and at least to some extent supplanted by a second one further to the south, possibly in Fujian. This temple, under a cantankerous abbot named Ji Sin, began sheltering rebels against Qing authority, and eventually extended to them instruction in the same kung fu techniques practiced by the monks themselves. Naturally, that did not endear the monastery to the Qing emperors, and in order to extirpate an increasingly worrisome nest of Ming sympathizers, the second Shaolin Temple was sacked and burned. A handful of monks and lay disciples survived the siege, however, and became the progenitors of all Southern Chinese martial arts.

Understand, though, that thereís barely a word of verifiable truth in any of that. For one thing, itís distinctly possible that the physical discipline practiced by the Shaolin monks in ancient times was closer to yoga than to kung fu, and that the shift to true martial arts training was a gradual, evolutionary process with no single instigator at all. And more importantly, the story of the southern temple rests on a foundation of shifting sand. Its burning has been attributed to three different emperors, and associated with six different dates, spanning nearly a century from 1647 to 1732. Some of the fugitive founders of southern kung fu are first attested in what are patently works of fiction, written long after their ostensible lifetimes. Indeed, it canít even be proven that the second Shaolin Temple ever existed in the first place, although there are several sites here and there in Fujian that each make somewhat plausible candidates to be its ruins. The main source for the entire narrative is oral tradition, subsequently recorded and codified by the various Southern Chinese kung fu schools, secret societies, and Triad mobs, all of which understandably put great stock in keeping track of who learned or received what from whom going back to time immemorial. But in the milieu of Chineseó and particularly Cantoneseó popular culture, those legends and lore far outweigh mere history, so that whenever you see the name Shaolin in a creative work touching on the martial arts, itís usually safe to assume that the mythical southern temple and its associated lineages of heroes are intended, rather than those somber savants contemplating the sutras at the foot of Wuru Peak.

Thatís certainly the case with the series of Shaolin movies that Chang Cheh directed for the Shaw Brothers studio in partnership with action director Lau Kar-Leung (although the latter was credited in most of them under the Mandarin reading of his name, Liu Chia-Liang.) Theyíre a curious bunch of films from an American point of view, insofar as they donít narratively follow one another, even if they can be rearranged to form something like a single coherent storyó especially if you intermingle them with the other sets of Shaolin pictures that Lau directed himself after he and Chang parted ways. Because the intended audience could be assumed to know the contours of the larger story, Chang, Lau, and screenwriter Ni Kuang used the individual installments to zoom in on whichever incidents or characters called to them in the moment, hopping freely about in the timestream, and trusting the viewer to keep up. Meanwhile, thereís even some indication that the order in which the films were released differs from that in which they were produced; for instance, if Lauís own memory is reliable here, Five Shaolin Masters was the first to get underway, even though it was released either third or fourth (depending on whether you count Shaolin Martial Arts as part of the series). Nevertheless, Iím going to treat Heroes Two, released in January of 1974, as the starting point. It is, after all, the first Shaw Brothers Shaolin movie that domestic audiences would have seen, and the speed with which the studio cranked these things out (three or four in 1974 alone!) is such that anything else would be too confusing.

Heroes Two begins with the southern Shaolin Temple already in flames, the monks and their disciples nearly all dead or fled, and the destroyer of the temple, General Che Kang (Chu Mu, from All Men Are Brothers and The Invincible Iron Palm), all but completely victorious. The one thing Che and his men havenít yet managed to do is to kill Hung Hsi-Kwan (Chen Kuan-Tai, of The Boxer from Shantung and The Water Margin), the last of the templeís defenders still fighting. Chang and company see no need to explain this, but Hung Hsi-Kwan (or Hung Hei-Gun to speakers of Cantonese) was a tea merchant descended from the fifteenth (!) son of the final Ming emperor, who found shelter at the Shaolin Temple after getting into trouble with the Qing authorities. He learned Tiger Claw kung fu from Ji Sin himself, and was arguably the most formidable of the lay disciples. Anyway, the point is that Che is adamant about not letting Hung escape, but no twenty of the generalís men are a match for the hero, even with a gimp leg and half a dozen minor stab wounds slowing him down. Cheís right-hand man, Lord Teh Hsiang (Wong Ching, who would return to the series as different characters in Men from the Monastery and Shaolin Temple), can make examples of as many poor sods as he likes, but insufficient motivation really isnít the problem here, and Hung slips away despite all their best efforts.

Hung Hsi-Kwan isnít the only Shaolin-trained fugitive running loose in Fujian (or wherever) right now, either. As Hung wends his way across the province, pummeling whatever Qing agents foolishly attempt to detain him, that teenaged prodigy of ass-kicking, Fang Shih-Yu (teenaged prodigy of ass-kicking Alexander Fu Sheng, from The Brave Archer and Na Cha the Great)ó also known as Fong Sai-Yukó is roaming about making life difficult for bandits, ruffians, and assholes of all descriptions. Normally that would make him one of the last people whom a Qing official would ever want to meet, but when another of Cheís associates, by the name of Mai Shin (Fung Ngai, of The Seven Coffins and The Comet Strikes), finds himself having lunch at the same restaurant as Fang, it gives him a wicked idea. What if somebody told Fang that there was a particularly dangerous highwayman at large? And what if somebody described that highwayman in terms that matched the appearance of Hung Hsi-Kwan, whom Fang knows only by reputation, because their respective tenures at the Shaolin Temple never overlapped? What if, in other words, it takes a Shaolin hero to catch Shaolin hero? Mai fixes it so that the next one of Cheís men to cross paths with both Hung and Fang aims the latter at the former. Even wounded as he is, Hung takes a long time to go down, but down he eventually goes, to be taken prisoner by Mai Shin.

Fangís first hint at how badly he just fucked up comes when he stops in at the bun-and-noodle joint run by a young widow (Fong Sam, from The One-Armed Swordsman and Ghost Under the Cold Moonlight), whose name we never learn, but whose Ming sympathies are unmistakable. Itís only to be expected when the proprietress snubs Fangís impertinent efforts to get into her pants, but then he gets an equally cold shoulder from all the other customers, too. And when Fang goes to visit an old friend of his a bit later, the exiled Ming patriot Li Shih-Chang (Wu Chi-Chin, of The Crimson Charm and The Flying Guillotine), he is initially denied entry by the young toughs whom Li has been training as revolutionary partisans. Even when Li himself lets Fang inside, it quickly becomes apparent that he isnít really welcome, and that the older man now considers the younger one to be somehow a traitor to the Ming cause. What follows is half argument and half brawl, with the physical side prevented from becoming truly deadly only because everyone involved understands that Fang could wipe the floor with Li and all his followers in his sleep. Eventually, however, the combatants manage to get enough words in edgewise for the truth to come out: that Fang was bamboozled into handing Hung Hsi-Kwan over to the hated Qing. After much melodramatic begging for death (the truly well-versed viewer will realize that Li would find it difficult to grant such a request in the first place, since Fangís childhood training has rendered his skin as impenetrable as any suit of armor), the disgraced hero vows to make amends by finding and freeing Hung before General Che can either execute him or (horror of horrors!) torture out of him any information that might help the Qing find the other escapees from the Shaolin Temple.

I canít deny that Heroes Two is tough going for the uninitiated. For instance, if youíve never heard of Fang Shih-Yu, Iím sure itís terribly disorienting when every utterance of his name throughout the second act is accompanied by both a musical sting and a sudden shift in focus to the worried face of the nearest Manchu. Similarly, those unacquainted with Shaolin kung fuís Five Animals theory may miss the significance of the pauses during the two heroesí fight when they each recognize one of the otherís moves (Hung Hsi-Kwanís Tiger Claw, and a strange, straight-fingered strike from the Crane repertoire for Fang Shih-Yu) as the mark of a natural ally. I canít remember the last time I felt compelled to do so much preparatory reading before watching a movie (as opposed to writing about one, which always entails a certain amount of homework), and I completely understand why normal people wouldnít want to make such an investment. Nor can I fault anyone who finds the characterizations flat, the motivations impenetrable, or the fact that the film both begins and ends in the middle of some unelaborated larger story unsatisfying. But if you have (or donít mind acquiring) the background necessary to follow all the things that it leaves unspoken, Heroes Two is a quite effective film that builds noticeably upon what Chang Cheh had already achieved in movies like Vengeance! and The Boxer from Shantung.

Lau Kar-Leung deserves at least as much credit for that as Chang himself. For the most part, Changís previous kung fu films were what veteran chopsocky fans refer to as ďbashers.Ē Their performers were, with a few exceptions, trained in the action techniques of Chinese opera rather than the martial arts in any strict sense, so however frenzied and dynamic the fight scenes were, they basically remained faster and more elaborate counterparts to the conventionalized brawls that one might see in any other nationís action cinema of the early 70ís. For the Shaolin cycle, however, Lau pushed Chang to incorporate recognizable, authentic Southern Chinese fighting styles, of the lineages that traced their descent from the actual (or at least ďactualĒ) Shaolin Temple. Lau was in a superb position to do so, too, for he was himself proficient in Hung Garó which he learned from his father, a student of a student of that ultimate post-Shaolin hero, Wong Fei-Hung. The difference is immediately apparent, to the extent that I frequently found myself thinking things like, ďOh! So thatís why itís called ĎTiger Clawí!Ē and ďOh! So thatís why itís the Crane style!Ē Furthermore, Lauís choreography is so adept that even the mostly untrained eye can detect a rough hierarchy of fighting skill and power among the filmís characters. Witness, for example, Chu Muís effortlessly economical dodges whenever General Che enters the fray, or the two heroesí virtual inability to lay hands on each other throughout most of their setup duel. I donít think Iíve ever seen cinematic fighting engineered to this standard before, even by people who are generally and deservedly counted among the greats.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact