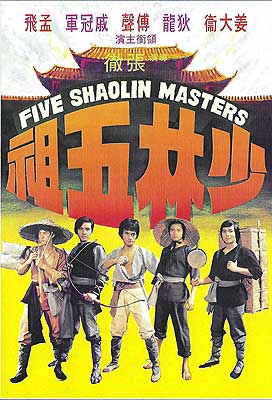

Five Shaolin Masters / Five Masters of Death / Shaolin Wu Zu (1974) ***Ĺ

Five Shaolin Masters / Five Masters of Death / Shaolin Wu Zu (1974) ***Ĺ

China, as you may have noticed, is an extremely large country, comparable in extent to the continental United States. It therefore offers plenty of territory in which to hide out should some asshole perchance burn down the Chan Buddhist temple where you and your buddies were studying kung fu with an eye toward maybe overthrowing the Qing Dynasty someday. So for all that the destruction of the Shaolin Temple is the founding myth of Southern Chinese martial arts, the legends of its aftermath have it that the refugees of Shaolin dispersed far and wide, bringing their proprietary ass-kicking techniques with them. The first two entries in Chang Chehís Shaolin Temple series for Shaw Brothers concerned themselves with the survivors who stayed more or less local, but the third, Five Shaolin Masters, takes up the story of those who escaped northward into the Chinese heartland. Although it has even more viewpoint characters than Men from the Monastery, it does a significantly better job of articulating how their individual trials and tribulations add up to a single, coherent story, even before it reunites them for the run-up to the final showdown.

The Shaolin Temple lies in ruins, having been sacked and burned by the forces of an unseen General Zheng. (Itís curious that each of the Shaolin movies so far has given a different name to the destroyer of the temple, despite all having been written, or at least co-written, by Ni Kuang over a span of mere months. I wonder if that might have been Niís sly way of acknowledging the multiple conflicting traditions regarding when and at which emperorís behest the temple was supposedly burned?) The attack would never have succeeded, though, if the Qing authorities hadnít had a man on the inside to feed them intel about the templeís layout and defenses. The emperor knows it, too, and so highly does he value the contributions of the traitor, Brother Ma Fu-Yi (Johnny Wang Lung-Wei, of The Avenging Eagle and Ten Tigers of Kwangtung), that heís sent him a special silken gown as a reward. But as we already know, the victory over Shaolin was not quite complete even so. A handful of monks and lay disciples, all of them formidably skilled in kung fu, managed to get away, including the fearsome Hung Hsi Kwan (who will not be appearing in person this time around). While General Zheng sees to the rather worrisome problem of Hungís escape personally, his ally, Magistrate Chen Wen-Yao of Renan (The Battle Wizardís Chiang Tao, functionally reprising his Men from the Monastery role despite officially playing a different character), will lead the efforts to round up the other fugitives of Shaolin.

As the title indicates, weíll be concerning ourselves with five of those this time around, led by Hu Te-Ti (David Chiang Da-Wei, of The Boxer from Shantung and The Water Margin). Hu is unexpectedly well traveled for a monk, and has contacts in the Ming restorationist movement all over the countryó including even in Taiwan! He figures the best thing for him and his remaining comrades to do at this point is to split up and make their ways separately to central China, in order to join with the pro-Ming rebels there. In particular, Hu hopes to ally the survivors of Shaolin with the bandit army led by ďIron FaceĒ Kao Fung (Li Chen-Piao, from Na-Cha the Great, who had previously played a miniscule role in Heroes Two), who is well known to be no friend to the Manchu. The brothers will be able to recognize fellow partisans by means of a system of secret signals (hand signs, coded behaviors, arrangements of objects, etc.) that Hu has already disseminated across the land during his travels. Even so, thereís some concern at first that Ma Chao-Hsing (Alexander Fu Sheng, stepping temporarily out of his usual series role as Fang Shih-Yu), the youngest and least disciplined of the bunch, will manage to fuck things up for everyone somehow or other. And of course none of the escapees can be absolutely certain that any of the others isnít the traitor whom theyíve all come to suspect sold them out to the Qing, even though we know whose doing that really was.

Meanwhile, Chenís informants bring to his attention rumors that the fugitives heís hunting are led by Hu Te-Ti; the magistrate already knows enough about Hu to recognize how his involvement could become ever-expanding bad news. Luckily for Chen, however, he also knows that his own province of Renan is a hotbed of Ming sympathy, and therefore one of the places where Hu seems most likely to go. He sets off to await the rebels, summoning four of the other martial artists who fought at the siege of Shaolin to assist him. It happens that each of Huís followers tangles with one of Chenís on the road northward, and although all live to tell the tale, they receive a series of very rude awakenings. Tsai Te-Chung (Ti Lung, from Vengeance! and Black Magic) is intercepted by Pao Yu-Lung (Tsai Hung, of Shaolin Kung Fu Master and The Silver Spear), an immensely strong bruiser who is furthermore master of a somewhat fanciful blade-on-a-string weapon called the Flying Axe. Li Shih-Kai (Chi Kuan-Chun, from Shaolin Martial Arts and The Ways of Kung Fu) runs afoul of the Mantis Fist master Chang Chin-Chiu (Fung Hak-On, of Kung Fu: The Punch of Death and Snake in the Eagleís Shadow). Fang Ta-Hung (Mang Fei, of The Invincible Kung Fu Trio and Kung Fu of Eight Drunkards), attempting to rescue a Ming patriot from the gendarmes transporting him to prison, comes up against Chien San (Leung Kar-Yan, from Ten Brothers of Shaolin and The Thundering Mantis); Iím not sure what Chienís fighting style is supposed to be, but heís fast as fuck, and poor Fang can barely get a punch in edgewise. And Ma Chao-Hsing, dope that he is, finds himself eating lunch with none other than Ma Fu-Yi, coming this close to spilling everything before he realizes that the elder Ma almost has to be the traitor who undermined Shaolin from within.

Although Ma doesnít kill Ma (this is about to get really confusing, isnít it?) in the fight that follows the latter getting the big lightbulb about the formerís role in the siege, he does capture him for a trip to the dungeon underneath Chenís place. In a sidelong way, though, thatís lucky for the kid even despite the array of torture equipment that greets him down there. Iron Face Kao suspects Hu of being the traitor when Te-Ti comes round to propose his alliance, and the arch-bandit places an onerous condition indeed upon his acceptance of the pact: Hu must first bring him Chen Wen-Yaoís head! Half of Kaoís men desert to help when Hu agrees to those seemingly impossible terms, and en route to Chenís compound, they encounter a witness to Ma Chao-Hsingís arrest. Word of the traitorís true identity changes Kaoís tune, and transforms the assassination attempt against Chen into a bid to rescue Ma, supported by the full might of the outlaw army. The results, however, are mixed to say the least. The Shaolin brothers and their bandit comrades succeed in springing the prisoner from the torture chamber unharmed, but Kao dies in the melee, and Hu discovers that heís no match for the clockwork-like teamwork of Chen and his twin bodyguards (Teng Chiang-Mei and Teng Chiang-Ying, who similarly played double-trouble fighters in Duel of the Masters and One Armed Against Nine Killers). Together with his fellowsí reports of the rough handling they got from Chenís chief minions, the scrap with the magistrate convinces Hu that a change of strategy is in order. While the bandits reorganize themselves under new leaders and seek new recruits to replenish their strength, the five Shaolin brothers sneak back to the ruins of the temple to train in new weapons and new techniques calculated to neutralize the advantages held by their hitherto unbeatable foes.

Five Shaolin Masters is conspicuously the best of Chang Chehís Shaolin Temple movies thus far. Itís also the most accessible for viewers not well versed in the legends of Shaolin or the intricacies of Southern Chinese kung fu. Chang and Ni Kuang prevent the numerous plot threads from snarling while also keeping them constantly in sight of one another, in contrast to Men from the Monastery, which frequently leaves it unclear until the fourth segment how events in the other three are meant to fit together. And while I suspect that a real savant of kung fu lore could expound at length on the cultural significance of Hu Te-Ti, Tsai Te-Chung, Li Shih-Kai, Fang Ta-Hung, and Ma Chao-Hsing, the film is perfectly comprehensible without any such knowledge, in a way that was not true at all of Heroes Two. In Five Shaolin Masters, itís enough to understand that the heroes are rebels against a corrupt and alien authority who have recently suffered a catastrophic defeat. Lau Kar-Leungís action direction is superb, to the point that close attention to the fights and training sequences can actually help the novice viewer get a handle on the multitude of different named kung fu styles that are invoked over the course of the film. (That said, itís a lot easier to understand the premises behind the animal styles than those of the parallel element forms, let alone Ma Fu-Yiís baffling Plum Blossom Fist.) And itís extremely impressive that a movie with no fewer than ten featured martial artists manages to present each of them as having their own distinct skill set and approach to combat.

Itís also worth looking at Five Shaolin Masters in comparison with Shaolin Martial Arts, a slightly earlier Chang Cheh Shaolin movie that falls outside the parameters of his temple series, strictly construed. Both films follow the stock chopsocky plot template, and emphasize the acquisition and mastery of specific skills as the secret to victory over villains who initially outmatch the heroes. In Five Shaolin Masters, however, kung fu is merely a means to an end. Itís the fight against Manchu oppression that matters, not scoring points for one school (or its implicit philosophical, religious, political, or ethnic affiliations) over another. When Li Shih-Kai studies the Ten Fist style (a mix of techniques from the repertoires of all five animals and all five elements) to counter Chang Chin-Chiuís Mantis Fist, he isnít out to prove something about the innate superiority of the Shaolin tradition, but is rather just seeking the tactical advantage that versatility brings. Also, this movie takes a much more grounded view of what advanced martial arts training might enable a person to do than Shaolin Martial Arts. Some of the heroesí feats after leveling up are a touch unrealistic, but thereís no downright magic on the scale of chi redirection or retractile genitals.

The sole serious fault I can find with Five Shaolin Masters is that with one vital exception, it gives short shrift to characterization. The villains are cartoonishly evil, while the heroes for the most part are singlemindedly goal-oriented and inflexibly noble (for values of ďnobleĒ applicable to 17th- or 18th-century China). Itís disappointing in comparison to Changís psychologically sensitive earlier work, and might be taken as a signpost toward the honor-obsessed ciphers that reputedly populate the movies of his 1980ís decadent period. Fortunately, though, Five Shaolin Masters has Ma Chao-Hsing to provide a bit of fresh air. It would be a waste of talent to put Alexander Fu Sheng in a movie and not let him cut up just a little, and while Ma isnít quite as striking or appealing as Fuís Fang Shih-Yu, he makes up for it by offering a surprising foretaste of the roles that would catapult Jackie Chan to stardom four years later. Ma is a bit of a twerp, a bit of a klutz, and a bit of a sucker, but his brothers can always count on him when the chips are down nevertheless. He also illustrates how complicated a quality courage can be, for although heís quick to run from an uneven fight, his demeanor in the torture chamber is recklessly brave, as he essentially dares Ma Fu-Yi to do his worst. The latter scene is this movieís counterpart to Fang Shih-Yuís Bugs Bunny-esque taunting of the gangsters in Men from the Monastery, and it sticks in the memory in much the same way.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact