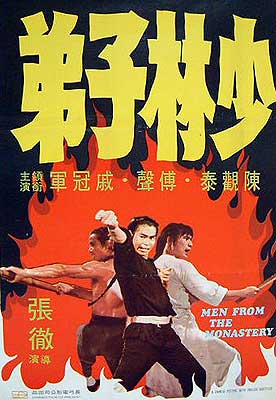

Men from the Monastery / Disciples of Death / Dragon’s Teeth / Shaolin Zi Du (1974) **½

Men from the Monastery / Disciples of Death / Dragon’s Teeth / Shaolin Zi Du (1974) **½

As I said in my review of Heroes Two, the series of sequels spun off from that movie does not comport itself at all like a Western film franchise. Instead of each successive entry picking up where the last one left off, Chang Cheh’s Shaolin Temple movies for Shaw Brothers wander all over time and space, switching focus from one character or group thereof to another, and assembling in mosaic fashion the highlights of a story which the audience was assumed to know already. Men from the Monastery, the second film in the series, does something even weirder than that, however. Although it brings back the stars of Heroes Two to revisit their former roles, it proceeds from a different version of the Shaolin Temple legend, irreconcilable in its details from the one assumed by its predecessor. In theory, the events of Heroes Two ought to slot in roughly three quarters of the way through Men from the Monastery, but in practice they can’t quite be made to fit.

Men from the Monastery is also peculiar in that it resembles an anthology film, but instead of having a framing story, it braids together the narratives of its first three segments to form a collective backdrop for the fourth. It begins by filling in one of the bigger lacunae in Heroes Two, establishing an origin for Fang Shih-Yu (a returning Alexander Fu Sheng). This time, we’re told of his mother’s practice of bathing him throughout his childhood in wine mulled with mystic herbs, rendering his skin so impenetrable that only a sword or spear thrust directly up his asshole will kill him. (And now I know where another of the weirder small details in Thrilling Bloody Sword came from!) We’re told of his headlong, impetuous race through the martial arts curriculum of the Shaolin Temple, although the film never specifies exactly how short he cuts what was supposed to be a three-year course of study. And we actually get to see Fang ace his final exam, so to speak, completing the ordeal of Wooden Man Alley with unprecedented ease. (Although some later Shaolin Temple movies would interpret the wooden or bronze men literally, as some kind of quasi-magical kung fu automata, Men from the Monastery takes a more grounded, metaphorical reading in which the student’s opponents in this rite of passage are Shaolin brothers who have so committed themselves to the task of testing the disciples to the limits of their powers that their hearts might as well be made of wood so long as the ordeal is underway.)

But Men from the Monastery also inserts a missing piece that novice viewers of Heroes Two might never have noticed was missing at all. Fang Shih-Yu’s prodigious development has been watched with anxious eyes by Feng Dao-De (Lu Ti, from Man of Iron and Illicit Desire), ostensibly one of the Shaolin Temple’s senior disciples. That’s because Feng is actually an infiltrator from the rival Wu Tang school of martial arts. Wu Tang (or Wudang) is Taoist rather than Buddhist; its associated kung fu styles are “internal” and “soft,” rather than “external” and “hard” like the ones practiced at Shaolin; and at least in the body of legendry underpinning these movies, it is aligned with the ruling Qing dynasty, rather than opposing it in the name of Ming restoration. Feng sends an assassin (Fung Choi-Bo, of Killer Clans and Friends) to lurk in the final chamber of Wooden Man Alley, and when the latter’s sword makes no impression on Fang Shih-Yu’s invulnerable hide, he improvises by stabbing the brother proctoring the test. Correctly figuring that the assassin will try to frame him for the murder, Fang skips out on whatever graduation ceremony there ought to have been, and slips away to his hometown. But neither Feng nor the killer are able to persuade Abbot Zhi Shan (or Ji Sin in the Cantonese reading) of their story. Obviously they’re going to be in trouble once the monks sort out what really happened, and their ally on the inside, Bak Mei, the treacherous White-Browed Priest, sends them away while the getting is good. (Curiously, neither Zhi Shan nor Bak Mei appears onscreen in this installment, being represented solely by a voiceover and a talking shadow respectively.)

Upon arriving on his old stomping grounds, Fang quickly reconnects with his friend, He Da-Yong (Fang Tak-Cheung, of Stranger from Shaolin and Master of the Flying Guillotine), and learns that an old enemy of his, Lei Lau-Hu (Huang Pei-Chih, from The Supreme Swordsman and The Heroic Ones), has ascended from mere hoodlumry to become a true menace to the community. Indeed, Fang comes home just in time to help He save his sister from being roughed up by a quintet of Lei’s followers as an inducement to the lad to pay back some money that he owes Lei. Fang naturally takes it upon himself to give Lei what for, but there’s going to be one small complication. The outlaw forces all challengers to face him atop something he calls the Pile Formation, which is a grid of man-high wooden posts erected above a forest of bamboo panji stakes. The merest loss of balance is thus likely to be fatal, let alone a careless misstep or a knockdown. Are even Fang Shih-Yu’s skills equal to such an unforgiving set of ground rules?

The second segment concerns a stubborn young bastard by the name of Hu Huei-Chien (Chih Kuan-Chan, from The Iron Monkey and Eagle’s Claw). Hu’s father (Wu Chi-Chin, of Heroes Two and The Bloody Escape) is an inveterate gambler, but a very successful one. One evening, the elder Hu makes the mistake of refusing to extend credit for another hand to two men whom he’s just finished cleaning out at some manner of domino game. The pair— their names are Niu Hua-Jiao (Wong Mei, from The Bloody Fists and The Delightful Forest) and Lu Ying-Bu (Lo Wai, of The Boxer from Shantung and The Water Margin)— are Wu Tang masters, leaders of the Jin Lun kung fu school, and proprietors of the associated textile mill. When Hu tells them that they won’t be getting any more chances to win back their money today, Niu and Lu beat him to death right there in the gabling den, and the corrupt gendarmes write off the murder as an accident. Obviously Huei-Chien isn’t going to stand for that, but his efforts to take revenge lead only to him getting the shit kicked out of him again and again. The younger Hu’s hapless one-man war makes him a hero to the townspeople, oppressed by Wu Tang gangsters and crooked officials alike, but everyone— most especially Hu’s teahouse-waitress girlfriend, Li Cui-Ping (Wu Hsueh-Yan)— recognizes that it’s certain to get him killed sooner or later. Then Hu makes the acquaintance of Fang Shih-Yu. After helping him out of his most serious scrape yet against the Jin Lun fighters, Fang steers Hu toward the Shaolin Temple. When Niu and Lu see Hu again three years later, it’s going to be a whole new ballgame.

Beating up outlaws and gangsters is all well and good, but as the official reaction to old Mr. Hu’s murder shows, it doesn’t do much to address a corrupt power structure. That’s where Hung Hsi-Kwan (Chen Kuan-Tai again) comes in. Hung puts his Shaolin Temple training to use preying on the agents of the Qing Dynasty itself— its soldiers, its police, its governing functionaries. He’s far from alone, either, for a small army of Ming Dynasty patriots, all of them similarly schooled in Shaolin martial arts, has coalesced around him since he got to work. Hung is the most wanted man in the province, and Lei Da-Pang (Wong Ching, from The Hammer of God and The Imp), the right-hand man of local military governor Gao Jin-Zhong (Chiang Tao, of The Fantastic Magic Baby and Na Cha and the Seven Devils), is moving heaven and earth to catch him. Not that it’s done him any good so far. But Lei has a right-hand man of his own, and this fellow is rather cleverer than his boss. (Lei’s sidekick is never named, but he’s played by Fung Ngai, and he performs essentially the same function as Fung’s character from Heroes Two. He even dresses the same! I therefore surrender to the temptation to think of him as this movie’s interpretation of the same figure, and will henceforth call him “Ming Sha.”) Whereas Lei thinks only in terms of capturing Hung’s followers in order to torture the other partisans’ identities and hiding places out of them, Ming conceives a plan to infiltrate the rebellion with two of his own men (Lam Fai-Wong, from Dreams of Eroticism and The New Shaolin Boxers, and Stephen Yip Tin-Hang, of The Brave Archer and Centipede Horror). What Ming fails to realize is that Hung and his followers, like all good revolutionaries, are intensely paranoid of exactly such tactics, and have laid their own traps accordingly.

Finally, General Gao decides that enough is enough. Knowing full well where the rebels against his authority are acquiring the skills that make them so troublesome, he sends an army to burn the Shaolin Temple to the ground. Even that isn’t quite the victory he was hoping for, however, because Hung Hsi-Kwan escapes, along with Fang Shih-Yu, Hu Huei-Chien, Li Cui-Ping (who turns out to be no slouch in the kung fu department herself), and eight or ten other Ming patriots. Withdrawing to somewhat safer territory, these last surviving rebels establish a new base in the ruins of the Qing Yun Temple (wherever that is), with the aim of continuing to make themselves as big a pain in Manchu asses as possible. Gao is bound to find them eventually, though, and next time he’ll bring along a contingent of Wu Tang fighters— including those two infiltrators to the Shaolin Temple, who have learned the secret of Fang Shih-Yu’s weakness.

It’s strange to say this about a kung fu movie, but I really do wish that Men from the Monastery had a little bit less fighting in it. Don’t get me wrong, the fighting is very good— well paced, expertly blocked, and above all communicative of each combatant’s ostensible skill level and personality. Action director Lau Kar-Leung has nothing to be ashamed of on that score. It’s just that there’s so little downtime that it gets tiring after a while. Also, precisely because this movie delves so much deeper into the legends of the Shaolin Temple than its predecessor, I wanted the story— or more accurately, the stories— to have more room to breathe. Men from the Monastery would particularly have benefited from more investment in developing the rivalry between the Shaolin and Wu Tang schools, and the connection between Wu Tang and the Qing government. But I suppose all that falls under the heading of “things the target audience was expected to know going in.”

That said, director Chang Cheh turns in some of the best work I’ve yet seen from him during those dramatic sequences that he’s able to squeeze in edgewise amid all the pummeling— and incredibly, one of those highlights revolves around a woman! In the latter scene, the formidable madam of a whorehouse (Wong Bing-Bing, from Women of Desire and The Savage Five) puts the fear of the Celestial Bureaucracy into a group of Qing gendarmes who start acting like hooligans in her brothel, without ever needing to call on the aid of Hung Hsi-Kwan (who is hiding out in one of the bedrooms) or having to throw a single punch. Then there are two sequences in which Chang manages to transform some of the weaker action set-pieces into highly effective bits of storytelling by interspersing them with well-observed moments of relative quiet. Hu Huei-Chien’s repeated drubbings ought to wear out their welcome, but Chang uses the interstices to build up Hu’s pigheaded obstinacy until he starts looking like a benign Yosemite Sam. Then, after Hu’s graduation from the Shaolin Temple, comes an even better example, as Fang Shih-Yu keeps the masters of Jin Lun busy with his insolent small-talk while Hu trashes their textile mill functionally unopposed. Indeed, the latter is probably my favorite scene in the whole film.

My main takeaway from Men from the Monastery, though, concerns neither Lau Kar-Leung nor Chang Cheh. Between this movie and Heroes Two, I’m just utterly taken with Alexander Fu Sheng’s portrayal of Fang Shih-Yu. If Hong Kong really needed a “next Bruce Lee” (a debatable proposition, to be sure), this is the guy who should have got the job. It isn’t just that Fu is the most impressive screen martial artist in a film that features quite a few of those, with speed and agility that never fail to sell Fang’s virtual invincibility. Fu also shares Lee’s rare combination of effortless charisma, puckish insouciance, and sheer physical beauty, to a degree that none of the actual Wannabruces ever approached. Fu steals every scene in which he appears, and for simple spectatorial joy, very little that I’ve seen in any kung fu movie so far can compare with Fu’s Fang looking bored and pretty while beating the asses of four or five overconfident bullies, without so much as bothering to put down his fan. Alas, there was one more thing that Fu had in common with Bruce Lee— he too died heartbreakingly young, fatally crushed in the passenger seat of his Porsche when his brother took a bend in the highway too aggressively for even a high-end European sports car to handle. The wreck came as the culmination to a whole series of career-interrupting accidents, which had twice seen Fu consigned to periods of forced idleness as the result of severe on-set injuries. He was in the midst of costarring, alongside Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, in 8 Diagram Pole Fighter at the time of his death. It’s hard to guess what might have become of him had he lived. Audiences abroad had mostly lost interest in kung fu by 1983, having grown infatuated with ninjutsu instead. Hong Kong, meanwhile, was on the verge of a massive shift in filmmaking fashion, in which martial arts movies per se went into eclipse behind the wave of stunt-based action pictures that furnished Jackie Chan with his second heyday. Plenty of 70’s stars like Fu went into eclipse as well, but I can’t help wondering whether his extraordinary screen presence could have sufficed to carry him on to continued stardom instead. If he’d lived, might Fu have become a transnational cult figure comparable to Chan, Jet Li, or Chow Yun-Fat? Would Western audiences have been asked to endure strings of awful buddy-cop movies pairing him with… I don’t know… Bernie Mac or one of the lesser Wayanses? In any case, 28 is just way too young for anyone to start collecting their salary in Hell Money.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact