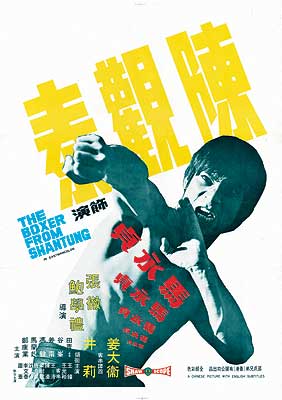

The Boxer from Shantung / Killer from Shantung / Shantung Boxer / Ma Yongzhen (1972) **˝

The Boxer from Shantung / Killer from Shantung / Shantung Boxer / Ma Yongzhen (1972) **˝

What’s a translator to do when not merely the word is foreign, but also the entire concept to which it refers? That was the quandary confronting the first British writers to come to grips with the subject of Chinese martial arts in the late 1860’s and early 1870’s. How to convey to the folks back home any sense of a practice that was at once military training, ascetic discipline, religious mysticism, quack medicine, and theatrical spectacle, when nothing meaningfully like that existed in their own experience? The solution arrived at by authors like Hong Kong colonial administrator Alfred Lister (who wrote extensively on many aspects of Chinese “low” culture for magazines like The North China Herald and The China Review) was to posit the notion of “Chinese boxing.” In some respects, it was a fair analogy. Both boxing and kung fu attempted to systematize beating the shit out of somebody, drawing upon a host of health-, strength-, and stamina-building regimens of sometimes dubious merit, even if their theoretical frameworks were of course very different. Also, in the mid-to-late 19th century, boxing and kung fu were similarly looked down upon by the elites of their respective cultures as something fit only for the most loutish elements of the lower social orders. But the comparison was confusing and misleading, too, because boxing in the English-speaking world has always been first and foremost a competitive sport, while that was about the one thing that kung fu definitely wasn’t in the days of the Qing Dynasty. The term stuck, though, at least in Hong Kong, so that by the time movies about Chinese martial arts really hit their stride 100 years later, it became common for the ones focusing on bare-handed fighting styles to bear English-language titles like King Boxer, The One-Armed Boxer, and The Boxer from Shantung. (Hong Kong movies made before the Beijing handover almost always had titles in both Chinese and English.) Outside of Hong Kong, though, where “boxing” just meant boxing, distributors were understandably leery of the possibility that audiences would mistake any film with that word in the title for a sporting drama. As a consequence, “boxer” movies more often than not wound up having their domestic English titles replaced with new ones abroad— and generally new ones contrived to call as much attention as possible to the orchestrated violence that was their main stock in trade. When The Boxer from Shantung made its way to the United States, it did so as Killer from Shantung instead. The new handle was inapt, insofar as the whole point of the film is that its protagonist dooms himself by attempting to build a criminal empire without serious bloodshed, but makes a fair enough teaser for the movie’s gore-soaked climactic battle.

Shantung, in case you were wondering, is a province on the east coast of China, although it’s usually spelled “Shandong” nowadays. Today, it’s the second-most populous province in the nation, but it was something of a backwater in the 1920’s, having been hollowed out by decades of colonial exploitation, first by the Germans and then by the Japanese. The kind of place, in other words, that anyone who could afford to escape would try to at the earliest opportunity. One such economic refugee is Ma Yongzhen (Chen Kuan-Tai, from Challenge of the Masters and Iron Monkey). One of many young men crowded cheek-by-jowl into a cheap hostel in some Shanghai slum, Ma supports himself as best he can with a variety of short-term gigs that require a strong back, but not much training: unloading cargo ships in the dockyard, digging trenches for laying water and sewer pipes, grooming horses and washing carriages at the local livery stable, that sort of thing. One day, he and his friend, Xiao Jiangbei (Cheng Kang-Yeh, of Kung Fu Zombie and The Blood Brothers), find themselves trying to perform the latter service for Triad boss Tan Si (David Chiang Da-Wei, from Shaolin Mantis and Vengeance!), but seem to accomplish nothing but to piss off his entourage. One of the men threatens to pummel Ma and Xiao, but discovers to his dismay that the former has serious kung fu skills. Indeed, Ma is so formidable that he even gives Tan Si a run for his money when the crime lord comes out to see what all the hubbub is about. Tan is mostly just toying with Ma, and so doesn’t press the advantage he ultimately gains, but Yongzhen makes enough of an impression that the gangster will be keeping an eye on him going forward. Tan Si makes an impression on Ma, too, who realizes as a result of their meeting that this guy has pretty much everything that Yongzhen came to Shanghai to get.

The next time Ma and Xiao have a little money to burn, they head over to the Pot of Spring teahouse to have a drink, and to hear the proprietor’s niece, Jin Lingzi (Ching Li, of Na Cha and the Seven Devils and The Brave Archer, Part III), sing a song or two. But because this is a kung fu movie from the 1970’s, the lads find the teahouse engulfed in a battle between Tan Si’s men and a rival gang somewhat ironically called the Four Champions. Evidently the latter aim to seize control of the neighborhood from the former. Ma doesn’t set out to take part in the fight, but when Four Champions goon Li Caishun (Ting Chin, from Trilogy of Swordsmanship and The Water Margin) offers him violence out of sheer dickishness, Ma is happy to take him up on it. Ma gives Li a stomping he won’t soon forget, then repeats the process with the next man up the chain of command, “Hatchet” Zhiang Jinfa (Ku Feng, from The One-Armed Swordsman and Vengeance of a Snowgirl). Finally, he fights the leader of the Four Champions, Fang Ah-Gen (Fung Ngai, of Heroes Two and The Eagle’s Claw), to a standstill which the latter man is strategist enough to recognize as placing him on the defensive. All Fang can really do at that point is to make blustery noises about squaring up accounts with the interloper later, before withdrawing with as many of his men as can still walk under their own power. Fang is then surprised a second time when he reports the incident to his own boss, the arch-criminal Master Yang (Chiang Nan, from Call Girls and The 36th Chamber of Shaolin). Although he does order Hatchet Zhiang to pay this Ma Yongzhen a visit in order to feel out his intentions and loyalties, Yang decides to make no direct move against the upstart— or at any rate, not until after he’s finished outmaneuvering Tan Si in some delicate business involving an international opium deal.

Normally when somebody whips the asses of a Triad mob somewhere, that person becomes the new holder of whatever economic rights in the area are recognized by organized crime. By those rules, Ma is the new boss of record in the vicinity of the Pot of Spring, since he beat the Four Champions after they finished beating Tan Si’s men. All the protection money that the teahouse owner (Chan Ho, of The Iron Buddha and Village of Tigers) and his neighbors used to pay to Tan therefore “rightfully” belongs to Yongzhen now. Ma doesn’t realize that, however, until several weeks later, when he returns to the Pot of Spring with all the other poor shlubs from the hostel to spend some of his winnings from a mob-run tournament where would-be tough guys paid for the privilege of matching their strength and fighting skills against those of an enormous Russian (Mario Milano, from The Zebra Force and The Spectre of Edgar Allan Poe). Upon his arrival, Jin Lingzi’s uncle presents Ma with a chest containing all the kickbacks he’s “earned” since chasing off the Four Champions, at which point Yongzhen realizes all of a sudden that he really has put himself on the road to becoming the next Tan Si, almost completely by accident. It isn’t for nothing that the first two luxury items he buys with his protection-racket windfal are a carriage and a porcelain cigarette holder, each of them just like Tan’s.

Ma means to do things a little differently from the typical crime boss, however. His gang, for starters, will be recruited from the other residents of that shitty hostel, establishing right from the start that loyalty in his mob is going to be a two-way street. Even Xiao Jiangbei, who is conspicuously not cut out for a life of crime, will benefit from Ma’s patronage, becoming his personal chauffeur and groom. Then there’s the matter of protection money. Ma’s going to keep collecting it, of course, at the same rates and on the same schedule that the folks at the Pot of Spring and their neighbors are accustomed to, but he’s going to let them run tabs when they need to, rather than having his men rough them up when they fall into arrears. And if Jin Lingzi should decide that he’s a creep for going into the crime business (which she does), Ma won’t try to use his position to force her to be friendlier toward him. Besides, it’s immediately obvious to Ma that there’s only so much profit to be extracted by skimming off the legitimate earnings of shopkeepers, restaurateurs, and street vendors. The real prizes are all to be found in the underworld economy: gambling, opium, prostitution, etc. And while there isn’t any of that on the turf which Ma has stumbled into running (which goes some way toward explaining why Tan Si is content to let him keep it), there’s plenty on the next street over.

The trouble, naturally, is that that street belongs to the Four Champions, and ultimately to Master Yang, although they’re no more able to prevent Ma from taking it from them by force than they were at the Pot of Spring. Again Yang is remarkably tolerant of having a piece of his empire peeled off, but again that’s only because he’s busy at the moment frying a much bigger fish. Yang’s spies inform him that those opium negotiations between Tan Si and his overseas suppliers are almost complete, and once they’re fully finalized, Yang means to have another underling of his named Lu Pu (Wong Ching, from Five Fingers of Death and Shaolin Temple) set up an ambush. With Tan Si dead, his suppliers will have little choice but to deal with Yang instead, and then the master of the Four Champions can turn his attention to that pain in the ass, Ma Yongzhen. Unless, of course, Ma were to come to Tan’s rescue, turning their tacit noninterference pact into a proper alliance.

Ma Yongzhen is another of those mytho-historic figures in the development of kung fu, specifically a magnate on the 19th-century horse-racing scene who was credited with introducing a fighting style called Chaquan to Shanghai. The Boxer from Shantung wasn’t the first movie made about him, nor was it anywhere close to the last, but its creators— writer Ni Kuang, co-director Pao Hsueh-Li, and director/co-writer Chang Cheh— do seem to have been the first to make the odd decision to pull Ma out of his native Qing Dynasty timeframe, and to drop him in the Warlord Era of the 1920’s-1930’s. Most subsequent Ma Yongzhen films— including an official sequel to this one called Man of Iron, at least two unofficial sequels made for studios other than the Shaw Brothers, and a bunch of Boxer from Shantung remakes— seem to have followed suit. I don’t pretend to understand what Chang, Ni, and Pao were thinking, unless maybe it was just that Qing settings were for wuxia, and that a kung fu crime melodrama required a habitat at least slightly more modern.

In any case, what struck me hardest about The Boxer from Shantung was that it really is a crime melodrama. Indeed, without all the fisticuffs, it could just as well have been a Warner Brothers gangster flick of the Pre-Code era, with Little Caesar offering the clearest parallel. Like Edward G. Robinson’s Rico Bandello, this version of Ma Yongzhen builds himself up from an easily ignored nobody into a gangland player whom even the most powerful have no choice but to take seriously. That might seem at first like an odd influence to encounter in a kung fu movie, but remember that the last Chang Cheh film we looked at, Vengeance!, was basically a noir with some of genre markers transposed. So why not reach back one more decade to raid the crime pictures of the Depression for inspiration too? Note, however, that there’s an important respect in which analogizing those movies to The Boxer from Shantung will lead your expectations astray. The natural assumption is that Jin Lingzi is destined to become Ma’s moll, but in fact that never happens. What’s more, the fact that it doesn’t is treated as an important element of Ma’s quixotic quest to be a noble, honorable criminal.

The really weird thing about The Boxer from Shantung, though, is that it’s the only kung fu movie I’ve seen so far in which the story, the acting, and the imagery— all the things one looks for in films from more respectable genres— are leagues ahead of the fight scenes. Frankly, the fighting here sucks, and anyone who comes to The Boxer from Shantung for the usual martial arts thrills is setting themselves up for disappointment. There’s no rhythm, no dynamics, no flow. The fight scenes drag on endlessly, with little sense of pacing and far too much repetition. Star Chen Kuan-Tai’s impish charisma vanishes without a trace every time he clenches his fists, and although he was an accomplished martial artist in real life, his abilities make no impression on the camera. Maybe part of the problem was that Chang Cheh was still operating in “basher” mode at this point in his career, leaving Chen without any proper foils against whom to show off his moves. Heaven knows Lau Kar-Leung would coax some riveting physical performances out of Chen two years later, in the Shaolin Temple series! But whatever the reason, it’s downright inexcusable for a fight that begins with one of the major combatants taking a hatchet to the gut to be boring.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact