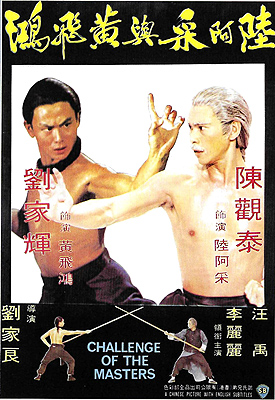

Challenge of the Masters / Liu A-Cai yu Huang Fei-Hong (1976) **½

Challenge of the Masters / Liu A-Cai yu Huang Fei-Hong (1976) **½

Wong Fei-Hung is a little different from most of the other Chinese folk heroes we’ve been meeting in 1970’s kung fu movies. For one thing, it’s certain— or as certain as it’s possible to be about any private individual a century after their death— that he was a real person, and not a fictional character, a composite of several otherwise obscure historical figures, or some other form of after-the-fact cultural creation. While it’s true that many of the stories told about him belong more to the realm of tall tales than that of biography, none of them are overtly fantastical, and would-be scholars of Wong’s life and legacy have a firm factual basis from which to begin. We know the dates of his birth and death, the names of both his hometown and the hospital where he breathed his last, and the approximate location of his burial site (even if the grave itself was apparently built or landscaped over at some point). We know at least the family names of all four of his wives, together with the years when he was married to each. We know which of those women bore which of Wong’s six children, and we know the names of all four of his sons (Wong’s two daughters, in contrast, are complete enigmas, which probably shouldn’t surprise anyone.) We know when and where he established his martial arts school, along with when and where he practiced Chinese folk medicine. We might even have a photograph of Wong Fei-Hung, although it’s harder to be certain about that. A few different “only known photos” of Wong have popped up over the years, each depicting a different, albeit always similar-looking, man.

But the more important difference separating Wong Fei-Hung from Hung Hei-Gun, Fong Sai-Yuk, Yim Wing-Chun, and the rest of that lot is the reason for his legendary status. Wong might have been a great master of Hung Gar kung fu, but he was at least as famous for making peace as he was for kicking ass, and the legends about him stress his wisdom and benevolence above his fighting prowess. Makes sense for a hero who was also a healer, don’t you think? The thing about wisdom, though, is that nobody is born with it. It has to be acquired and honed, and both the acquisition and the honing are the work of a lifetime. It’s therefore an interesting creative exercise to ask what such a hero might have been like before they became any wiser than the average schmuck. As circumstance would have it, both of the Wong Fei-Hung movies to come my way since I launched this website have proceeded from that off-model premise, rather than dealing with the hero at the height of his abilities. Drunken Master famously plays the idea for laughs, imagining Wong as a mischievous adolescent jackass, naturally gifted in martial arts, but also a prankster, a troublemaker, and a shirker of responsibility. Challenge of the Masters, an early directorial effort from longtime Shaw Brothers fight coordinator Lau Kar-Leung, is the straight-faced version. It depicts the young Wong as a well-meaning hothead unfairly written off by his father as ill-suited to the discipline of kung fu, but who turns out to need exactly that in order to begin fulfilling his spiritual potential.

Lau’s Wong Fei-Hung is his favorite star from this phase of his career, Gordon Liu Cha-Hui (who can also be seen in Shaolin vs. Evil Dead and Executioners from Shaolin). His disapproving father, Wong Kei-Ying, is Chiang Yang, from The Evil Karate and Infra-Man. And the proximate cause of both Fei-Hung’s desire to learn kung fu and Kei-Ying’s reluctance to teach it to him is a New Year’s Day tradition in which students of all the local martial arts masters form up into teams to capture— by any means short of actually fighting— as many as possible of a bunch of small cylinders called pao after they’re launched into the air above the town square by an array of fireworks. I count six teams in all, but the only ones we’ll be concerned with are those sponsored by Lu Ah-Tsai (The Iron Monkey’s Chen Kuan-Tai, with an old-age dye-job much less persuasive than the simple gray streak he wore in Crippled Avengers) and Pang Yun-Kang (Shih Chung-Tien, from The Way of the Tiger and The Guy with Secret Kung Fu). Lu is another pivotal figure in the legendarium of Southern Chinese martial arts, with a lineage of instruction supposedly reaching back to Hung Hei-Gun himself, but to put it in crassly anachronistic terms that everyone will grasp at once, he’s this movie’s Mr. Miyagi, while Pang’s school is Cobra Kai. Fei-Hung’s best friends, Tsang Hang (Cheng Kang-Yeh, of Five Tough Guys and The Lizard) and Yeung Cheung (Fung Hak-On, from The Young Dragon and Heroes Two), both study under Master Lu, which Wong wishes he could do as well. In contrast, Pang’s two leading pupils, Ren Leung (Chiang Tao, from Five Shaolin Masters and The Clones of Bruce Lee) and Ah Lung (Ricky Hui Koon-Ying, of To Hell with the Devil and Mr. Vampire), are the biggest dickheads in all Guangzhou. Along with coveting the glory that would be his as part of a winning pao-grabbing team, Wong seethes at the small but persistent injustice of watching those bastards from Pang’s school cheat their way to victory year after year.

Meanwhile, two strangers arrive in town. One of these is a shady-looking fellow called Ho Fu (director Lau, whose other onscreen credits include Legend of the Drunken Master and Heroes of the East), who redoubles the impression of shadiness by seeking lodging with Pang Yun-Kang. Then he redoubles it again by acknowledging, when pressed by Ren Leung and Ah Lung, that he knows an extremely deadly kung fu technique called the Sharp Kick, and is trained in a spear-fighting style that even the thoroughly unscrupulous Master Pang has forbidden his followers to learn. The other newcomer to Guangzhou isn’t entirely a stranger, for he was once a pupil of Lu Ah-Tsai, and his tutelage coincided with that of Wong Kei-Ying. Yuan Ching (Lau Kar-Wing, from Shaolin Martial Arts and Call Him Mr. Shatter) is now an agent of the imperial police, and what brings him to town is a manhunt for a notorious bandit who is rumored to have settled there recently. He’s talking about Ho Fu, of course, although Yuan knows him by a different name.

It happens that Wong Fei-Hung is the first person Yuan meets upon arriving at Lu’s compound, because the kid has developed a habit of hanging out beside the front door, never quite working up the nerve to go inside and apply as a student. Something about Fei-Hung’s timidly persistent vigil makes a positive impression on the kung fu cop, an impression which further observation seems to confirm. Yuan therefore persuades his old sifu to invite the boy in, and to offer him the instruction that he seeks. In fact, once Lu realizes that the kid on the doorstep is the son of one of his most talented protégés, he offers Fei-Hung not just admission to his school, but the kind of intensive, one-on-one tutoring that puts students on the road to becoming masters in their own right. Wong, meanwhile, is able to do Yuan a solid in return, because he’s noticed Ho Fu sneaking all over town like a man with 10,000 things to hide, and was once even asked by him if he knew anything about Yuan.

The downside of learning kung fu the way Wong is about to start doing it is that it demands every single last bit of your attention and concentration, and even then it isn’t quick. Lu takes Fei-Hung out of the city to his hermitage in the woods, where the two of them stay for three years, pretty much living kung fu. Wong slowly and painfully learns both Hung Gar and Eight-Diagram pole fighting, but more importantly he learns patience, self-discipline, and emotional control. Most of all, he learns a true and proper respect for violence, including a full appreciation of its seriousness, of the irrevocability of its results, and of the price it exacts from the soul of the person inflicting it. Wong emerges from Lu’s cabin in the hills knowing not only how to fight, but also when to fight, when to stop, and how to interrupt the cycle of violence to foster lasting peace and reconciliation. He’s going to need all of those lessons once he gets home, too, because in his and Lu’s absence, Ho Fu has slain Yuan Ching, and Master Pang’s students have run so totally amok that the next New Year’s festivities are likely to devolve into a mutual mass beat-down between them and the benevolent but prideful followers of Lu Ah-Tsai.

I recall reading that Lau Kar-Leung believed Hong Kong’s kung fu movies of the early 70’s didn’t pay enough attention to the philosophical side of the martial arts, but Challenge of the Masters marks the first time I’ve seen him recognizably trying to lead by counterexample. After focusing so much of my chopsocky education on the blood-soaked oeuvre of Chang Cheh, it’s pleasantly jarring to encounter a hero who rejects vengeance, eschews killing, and is absolutely serious about the paradox of turning violent means to peaceful ends. And now that I’ve seen Challenge of the Masters, I retrospectively detect some of those same concerns animating Lau’s slightly later kung fu comedies, Heroes of the East and Dirty Ho. Hell, it’s even possible that one of the reasons why Executioners from Shaolin never quite comes together is because Lau was trying futilely to shoehorn this movie’s humane outlook into the merciless and uncompromising milieu that Chang had already built for the series that it brings to a close.

To see what I’m really talking about here, compare Wong Fei-Hung’s reaction upon learning of Yuan Ching’s murder to his actual conduct during the showdown against Ho Fu two years later. Wong is so determined at first to avenge the man who secured for him his long-coveted slot under Lu Ah-Tsai that Lu can barely restrain him from chucking the rest of his training and charging back home to get his ass pointlessly kicked. But once Fei-Hung’s course of instruction is well and truly complete, and he goes to square up with the bandit on a more realistic basis, the battle is remarkably devoid of emotional heat on Wong’s part. Significantly, he announces right up front his intention not to kill Ho, but to turn him over to the proper authorities. And in fact Wong relents in his onslaught as soon as he has disabled Ho too severely for him to continue the fight, or even to run away. It’s an interesting sequence from a tonal perspective, too, in ways that tie directly into the theme of violence wielded with righteous mercy. I’m used to kung fu movies positioning their heroes as underdogs during the final fight, but Wong Fei-Hung gains the upper hand over Ho Fu very early on, and maintains it without even temporary reversal until the end. Wong fights with the serene implacability of divine justice, while Ho plainly recognizes that he’s fucked from the moment his enemy disarms him of his spear. The bandit’s increasingly palpable fear of what’s coming his way is important to the fight’s denouement, insofar as it humanizes him sufficiently to justify Wong’s commitment to sparing his life. In much the same way as Lau’s fight choreography in the Shaolin Temple series made the technical aspects of Southern Chinese kung fu legible to non-practitioners, his direction during this fight exemplifies the philosophical side.

If the Wong/Ho fight really were the climax to Challenge of the Masters, I’d be significantly firmer in my support for this film. Alas, though, the bandit and his activities are merely the B-plot, and there’s a bigger, dumber concluding set-piece waiting in the wings. The real finale is instead the next New Year’s celebration, bringing to a head the long-running conflict between Lu’s school and Pang’s. This too becomes an occasion for Wong to display his newfound wisdom alongside his newfound badassery, but on terms a great deal less satisfying than what we just saw. Once again, Wong “wins” by refraining from pressing an advantage to its utmost, but this time that means allowing the captain of Pang’s team to capture a pao after establishing beyond question that Fei-Hung could hang onto it indefinitely if he really wanted to. By voluntarily accepting a nominal loss of face, Wong demonstrates to opponents and teammates alike how little their annual rumbles mean in the grand scheme of things— and that’s exactly the problem from the standpoint of narrative construction. All along, the rival-schools plot has felt annoyingly like a Shaw Brothers riff on The Bad News Bears, and Wong’s strategy for making final peace between the Lu and Pang factions confirms that it deserved to be taken no more seriously. Putting it to bed after the life-or-death duel against Ho Fu is just totally backwards and upside-down. It inverts not only the stakes of the two conflicts, but the relative solemnity of the intended morals as well.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact