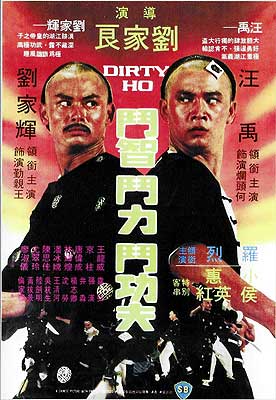

Dirty Ho / Lan Tou He / Laan Tau Ho (1979) ***

Dirty Ho / Lan Tou He / Laan Tau Ho (1979) ***

The late 1990’s and early 2000’s saw a conspicuous revival of American interest in Asian martial arts movies. Part and parcel of that was a reawakening of kung fu fandom among urban black audiences specifically— the same demographic that had embraced martial arts cinema most warmly when it first arrived on American shores 20-odd years earlier. To some extent, the latter phenomenon was just a knock-on effect of everybody going nuts for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, but I think it’s also fair to give some credit to the influence of the Wu Tang Clan, who were at the height of their popularity in those days, and who never let slip an opportunity to proselytize on behalf of their favorite film genre. The Wu Tang Clan connection certainly accounts for one of the funnier marketing fads of the era, as low-budget home video labels like Lion Video and Xenon Entertainment Group attempted to laser-focus their promotional efforts on people who wanted to see all the old kung fu films sampled on the group’s albums. In its simplest form, that could mean something like Lion’s practice of bundling together a rather random assortment of films to create a synthetic Rings of the Wu Tang series. But it could also mean giving an old movie a new title invoking the Wu Tang Clan directly, like when Xenon released Drunken Master, Slippery Snake as Ol’ Dirty Kung Fu. But the most desperate, and therefore the most amusing, variation on the theme was the “translation” of titles into what sounded suspiciously like a white 40-something’s idea of Ghettoese. Thus Duel of the Masters became Godz of Wu Tang; The Jade Dagger became Celestial Souljas; and most infamously of all, Bandits, Prostitutes, and Silver became Wu Tang Ho’s, Thugs & Scrillah. Incredible as it may sound, however, Dirty Ho was not one of those specious turn-of-the-century hip hop handles. Indeed, it’s what Shaw Brothers themselves called this movie wherever it played in Hong Kong with English subtitles!

It should go without saying, then, that that isn’t the sort of ho we’re talking about. Rather, this Dirty Ho is itinerant jewel thief Ho Ching (Wong Yu, from Challenge of the Masters and The Flying Guillotine). He recently pulled an extremely lucrative job, and as we meet him, he’s spending some of the proceeds aboard a riverboat brothel. So I guess we’re talking about that sort of ho after all, at least incidentally. Although Ho is entertaining and being entertained by a whole mob of girls, the two whom he really wants in his entourage for the night are Tsui Hung (Kara Hui Ying-Hung, of My Young Auntie and Chinatown Kid) and Tsui Bing (Helen Poon Bing-Seung, from Crippled Avengers and Clan Feuds)— or Crimson and Ice, as the English subtitles dub them. Tsui Hung and Tsui Bing are already spoken for, however, attending another big-spending customer by the name of Wang Chin-Chen (Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, of Shaolin Martial Arts and He Has Nothing but Kung Fu). To the equal pleasure and dismay of the madam (Lui Hung, of Human Lanterns and Sex Beyond the Grave), Ho and Wang fall into a bidding war over the disputed courtesans, ultimately provoking the former to dig directly into his coffer of pilfered jewels. But when Wang counters by producing an even bigger and more lavishly stocked treasure chest, his rival at last resorts to violence. Fearing lest her riverboat become the scene of a full-on brawl, the madam summons the gendarmes, who happen to be already in the area on the hunt for Ho. At first it looks like the hotheaded thief is bound straight for the nearest dungeon, but then something very curious happens. Discreetly flashing a jade seal that no one but a high-ranking member of the imperial court should possess, Wang explains to the police captain that there’s been a misunderstanding, and that his good friend, Ho— a traveling antique dealer like himself— has merely had a bit too much to drink tonight. Wang would very much appreciate it if the captain would detach a few of his men to make sure that Ho gets home safe and sound; he himself will hold Ho’s valuables for safekeeping until the morrow. Ho has no idea what any of this is about, beyond that Wang has just trapped him into handing over the jewels he stole earlier today. He’s smart enough, though, to keep his mouth shut, and to accept his police escort home.

Still Ho wants “his” jewels back, and he tries twice over the ensuing days to reclaim them. The first time, when he horns in on a meeting between Wang and a potential customer, Ho accomplishes nothing but to get the two of them waylaid by a quintet of ruffians posing as crippled beggars. The latter attack in a sly parody of Crippled Avengers when their ostensibly blind leader (San Sin, who played comparable bit parts in everything from Heroes Two to Red Spell Spells Red) overhears Ho and Wang arguing about the contested loot in the alley where the bogus beggars ply their trade. Ho fights his way out, while Wang bribes a bystander to sneak him to safety. Then, some time later, Ho returns to the riverboat brothel, on the theory that Wang is likely to be there as well. This time, Wang concocts an elaborate ruse claiming Tsui Hung as his bodyguard, which he substantiates by “stealthily” puppeteering her to a draw in the ensuing kung fu fight against Ho. Incensed, Ho pulls a knife, whereupon Wang hands Tsui Hung a sword. One shallow gash to the forehead is enough to convince the thief that he’s been foiled once again.

There’s more going on here than meets the eye, however. While Ho pursues his fruitless efforts to regain his lost treasure, General Liang Jing-Cheng (Lo Lieh, from Five Fingers of Death and Executioners from Shaolin) is delievering a report on Wang Chin-Chen to some unseen personage even more exalted than a top-ranked military commander. The true situation will come out only a piece at a time in the film itself, but I’m going to make this easier on you and me alike by spelling it all out up front. Liang is working for the fourth (Wai Wang, from Revenge of the Zombies and The Hookers and the Hustlers) of fourteen imperial princes. Wang is actually the eleventh such prince, roaming incognito around the empire because he finds court life unutterably dull and stifling. As we’ve seen, he’ll still pull the strings available to an emperor’s son when it suits him, but he’d much rather spend his time contemplating the beauty of artistic treasures, enjoying the company of stimulating women, and honing his skills and discipline at kung fu. Nevertheless, his ambitious elder brother fears that the emperor (Shum Lo, from The Cave of the Silken Web and The Dragon Missile) will choose Wang when he designates the official heir to the throne in a few weeks. After all, it would be just like the old man to decide that the one prince who would absolutely hate ruling the empire was for that very reason the only one qualified to do so. And since duty and filial piety are things that Wang does value highly, he’d surely accept the throne if their father insisted that he sit on it. The fourth prince has therefore set Liang to find the eleventh— and now that that’s done, the general will be charged to arrange his assassination, too. Liang figures that Wang’s estheticism is his weak point, for his habit of meeting, alone and in person, with dealers in and collectors of art, antiques, and so forth creates an infinity of opportunities for entrapment. Indeed, Liang knows of two such men right there in town— wine connoisseur Fan Tian-Kong (Johnny Wang Lung-Wei, of Five Shaolin Masters and The Brave Archer) and Ming vase enthusiast Chu Yi-Feng (Wilson Tong Wai-Shing, from The Iron Monkey and The 36th Chamber of Shaolin)— whose scruples are sufficiently lax, and whose fighting skills are sufficiently sharp, to make them usable as weapons against the wandering prince.

Meanwhile, Ho is dismayed to realize that his headwound isn’t healing. Eventually, he finds a doctor who correctly diagnoses the problem: the sword that Tsui-Hung slashed him with was poisoned, and unless Ho can discover what specific treatment was used on the edge, there’s nothing that anyone can do to cure him except by dangerous trial and error. So Ho goes once more to the riverboat, this time seeking the secret of the poisoned blade. Imagine his horror, then, when the madam informs him that Wang bought Tsui-Hung from her the other day in order to manumit her. Now there’s nothing else for it but to track down Wang yet again, but the wily bastard imposes an altogether unexpected condition in exchange for the antidote to the toxin sabotaging Ho’s platelets. If Ho wants his forehead to return to normal, he must accept Wang as his master— not in the sense of becoming his servant, but rather by submitting to apprenticeship under him. Wang means to teach Ho some proper-ass kung fu to supplement and eventually to supersede the admittedly effective street-brawling techniques he already knows, because the incognito prince is well aware that he’s being hunted. It was one thing to pretend that a courtesan was his bodyguard when Ho was the most formidable opponent he was likely to face, but now things are serious. If the eleventh imperial prince wants to stay ahead of the fourth one long enough for their father to announce his successor, thereby eliminating (or so Wang hopes) the cause of the sibling rivalry, he’s going to need a sidekick as well-versed in the martial arts as he is. And while taking sides in a battle over the future of the imperial throne might not sound like Ho’s idea of fun, it certainly beats having a scalp cut that never heals.

Fans of the genre often refer to the “Seasonal formula” when talking about kung fu comedies— “Seasonal” as in Seasonal Pictures, the studio most responsible for giving cinematic depictions of the Asian martial arts a sense of humor in the late 1970’s. In fact, though, there are two Seasonal formulas. In one of them, a hapless putz who starts off with little or no fighting skill learns kung fu to turn the tables on his bullies. It’s like a 1970’s comic book ad for Charles Atlas’s “Dynamic Tension” strength-training system come to life. And in the other, an arrogant kung fu master gets some humility beaten into him by the villain, and must then humble himself even further by submitting to some old weirdo’s torturous training regimen. We’ve looked at examples of both forms here over the years; the first is Half a Loaf of Kung Fu, while the second is Drunken Master.

What’s most remarkable about Dirty Ho is that it doesn’t really fit either paradigm. Ho can handle himself in a fight during the first act, but he isn’t really a kung fu master. Nor is he arrogant so much as just crooked, and annoyed that some son of a bitch even trickier than himself keeps cheating him out of the jewels he stole fair and square. And although Wang Chin-Chen is certainly Ho’s nemesis at first, he hardly qualifies as a bully. Furthermore, Wang ends up being the one to train Ho so that he can level up for the deadly battles of act three. It’s also worth observing that Ho is a much more serious transgressor against order and authority than any of the kung fu rapscallions I’ve seen played by Jackie Chan, Donnie Yen, or Alexander Fu Sheng. I mean, the guy’s a jewel thief, and unlike Freddy Wong, Chan Cheun-Cheng, or Tam Tung, I think we’re supposed to read him as a fully fledged adult instead of a gadabout youth. It may be, however, that screenwriter Ni Kuang (yep— him again!) felt constrained by history to steer at least a little bit clear of the Seasonal Formulae here. I’ve come across just the faintest traces of evidence that Dirty Ho (or more accurately, Rotten-Head Ho) is another of those mytho-historic founding fathers of kung fu that keep showing up in these movies, and that he’s associated with a Shaolin-derived fighting style called the Ten-Shapes Comet Fist. At the very least, this isn’t the first movie made about the character. Wu Pang, who directed many of the Wong Fei-Hung films starring Kwan Tak-Hing, also helmed The Cremation of Rotten-Head Ho way back in 1959.

Dirty Ho is unusual too in how its comic technique evolves over the course of the film, more or less in step with how much we’re allowed to know about the conflict driving the action. Initially, when all we know about Wang is that he’s a very rich man with extremely enviable connections, Dirty Ho plays rather like a kung fu variation on those Bugs Bunny/Daffy Duck cartoons from the early 1950’s, in which Bugs is forever turning Daffy’s malicious schemes back on him. No matter how ingeniously Ho tries to invoke Wabbit Season against Wang, the prince always finds a way to make it Duck Season instead. Then after Ho gets blackmailed into becoming Wang’s apprentice, we get something a bit closer to the expected “eccentric sifu/delinquent student” dynamic— except that Ho is much more openly hostile in his noncompliance than the typical pupil in that situation. And finally, after Wang is seriously injured by one of General Liang’s hit men, the jokes start revolving around the rapidly escalating zaniness of the villains, as the hunt for the eleventh prince is entrusted to a septet of oddballs called the Seven Agonies of the Orient. Their leader, a flamboyant yet aging and leathery homosexual played by The Sexual World’s Lee Ging-Fan, should suffice to convey some idea of the team’s overall vibe.

But whatever the mode of humor, director and action choreographer Lau Kar-Leung makes sure that the fights are in keeping with it, and that they serve as one of its primary means of delivery. The finest examples are the several fights in which one or both combatants are trying to maintain plausible deniability over whether they’re even fighting in the first place. I’ve already mentioned Tsui-Hung’s ostensible defense of Wang at the brothel, but it’s worth bringing up again to emphasize how funny it is to watch Gordon Liu slap Kara Hui’s limbs into position to block all of Wong Yu’s attacks, even as he makes a big show of hiding behind her. But the two fights against the connoisseur-assassins are even better, both of them staged to so as to slip the blows, blocks, and dodges in edgewise amid the seemingly sincere presentation and admiration of various artistic treasures. After all, Wang really does want to see these men’s collections, even if they are trying to kill him, and the assassins are as susceptible as any enthusiast to the ego boost of seeing their carefully curated hoards properly appreciated. The Shaolin Temple movies taught me to expect top-notch action from Lau, but I had no idea that he could be funny, too.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact