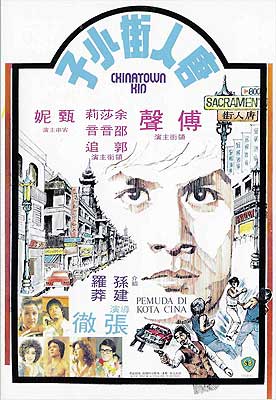

Chinatown Kid / Tang Ren Jie Xiao Zi / Tong Yan Gai Siu Ji (1977/1978) **½

Chinatown Kid / Tang Ren Jie Xiao Zi / Tong Yan Gai Siu Ji (1977/1978) **½

In 1977, Alexander Fu Sheng was one of the biggest kung fu stars in the Shaw Brothers stable— but only in Hong Kong. Somehow or other, Fu never really caught fire overseas, even in markets which ought to have been relatively easy lifts for him, like Taiwan and South Korean. He got even less traction in the West, where the chopsocky audience hadn’t embraced any performer in particular since the death of Bruce Lee, and wouldn’t until Chuck Norris broke big with The Octagon in 1980. Maybe part of Fu’s problem was that so many of his films had cast him as just one member of an ensemble, and often a confusingly large ensemble at that. That’s just a wild guess on my part, though. I find the movie-going preferences of my own culture baffling enough most of the time, and I certainly don’t lay claim to any insight into what audiences in Taipei, Seoul, or Singapore were thinking 40-odd years ago. Fu’s strange lack of international appeal feels like an important bit of background, though, for Chinatown Kid. This movie, one of director Chang Cheh’s first after returning home from an extended sojourn in Taiwan, is set not in the environs of the Shaolin Temple, the Martial World of wuxia, or the mythic realm of Journey to the West, but in the Chinese immigrant enclave of contemporary San Francisco. Fu, meanwhile, is unmistakably the singular star of the show. Chinatown Kid thus looks like a trial balloon for a trans-Pacific breakout that never happened. If so, I can’t say I’m surprised that it didn’t work. To all appearances, nobody at Shaw Brothers had any information on life in American Chinatowns more current than the 1930’s, and unlike Golden Harvest making The Big Brawl a few years later, they had no overseas partners on the project to set them straight when they needed it. Chinatown Kid’s San Francisco is thus a uniquely unconvincing place, the clamorous wrongness of which distracts and detracts from everything else the film attempts to do. And although Hong Kong audiences might have been willing to roll with the picture’s wrenching third-act tonal shift (or maybe not, since the much shorter reissue cut of Chinatown Kid comes to a markedly different ending), no gwailo wants to see an almost-comedy culminate in one of Chang Cheh’s signature Heroic Bummers.

Old Mr. Tam (Wong Ching-Ho, from The Vengeful Beauty and Shaolin Mantis) is the kind of down-and-out that used to be hard for people to reach unless they lived in some rapacious European power’s overseas colonial empire. He just about supports himself as an unlicensed fortune-teller, working wherever he can find sufficient space to set up his folding table in one of Hong Kong’s more downscale marketplaces. Then one day, Tam’s even more penniless grandson, Tung (Alexander Fu Sheng, of Cat vs. Rat and Shaolin Martial Arts), arrives from the mainland, apparently having swum across Victoria Harbor. That alone should be enough to tell you that Tam Tung is impulsive, almost superhumanly strong and tough, and rather on the dim side. Beyond that, we never really learn what the kid’s deal is, except that he acquired his physical prowess by practicing kung fu. In any case, the old man certainly can’t afford to support him, so he tries at first to find Tung regular work at a factory somewhere. Alas, no legitimate business will hire anyone without official Hong Kong identity papers, and Tung brought nothing with him but the clothes on his sopping-wet back. A similar obstacle seems at first to thwart the lad’s own suggestion that he and his grandfather open an orange juice kiosk like the obviously lucrative one beside which they set up the divination table the next day, because drink vendors need licenses, and licenses cost money (to say nothing of the expense of a fruit-juicing machine). But when Tung demonstrates his ability to squish all the liquid out of an orange with his bare hands, Grandpa realizes that they really could run a juice stand on the same law-dodging basis as his fortune-telling gig.

Alas, the pair’s success quickly attracts the attention of triad gangster Tsui Ho (Johnny Wang Lung-Wei, of Five Shaolin Masters and Dirty Ho). Partly Tsui Ho is annoyed to see somebody making money in the marketplace without giving him a cut, but he’s also intrigued by the odd spectacle of this young stranger tirelessly pulping oranges all day long without mechanical assistance of any kind. There’s only one way to get that kind of grip strength and muscular stamina, and whenever a new kung fu master appears in town, Tsui Ho wants to get him onto his mob’s payroll. The gangster offers Tung a “friendly” wager to the effect that he’ll hand over his expensive digital watch (the younger Tam has a thing for watches) if the kid can best him in a bout of sparring sometime. Grandpa sees that nothing good can come of that, however, and hustles Tung along on the plausible grounds that they’ve run out of oranges.

Tsui Ho gets his tryout match, though, when he catches Tung out for a late-night walk. It goes so badly for the gangster that he ends up forgetting himself, and pulling a knife— and then Tung really lays on the whoop-ass! Luckily for Tsui Ho, his more levelheaded wife (Teresa Ha Ping, from The Magic Blade and The Sugar Daddies) is watching from their limo. She puts a stop to the fight, and persuades Tam Tung to do the thing for which her husband was thinking of hiring him in the first place: to rescue her young cousin from the mob currently holding her hostage. That’s no problem for a total badass like Tung, but it turns out that the captive girl (Kara Hui Ying-Hung, from Clan of Amazons and Mad Monkey Kung Fu) isn’t anybody’s cousin. In fact, she’s a double abductee; Tsui Ho had already kidnapped her and forced her into prostitution before one of his rivals stole her away from him for the same purpose at a different venue. So instead of handing her back to her original abductors, Tung brings her home to her brother, and to relative safety. Tsui Ho’s revenge is swift and effective. He frames Tung for peddling heroin, and although the lad manages to evade the cops for a little while, there’s obviously a limit to how long he can keep that up. Fortunately, one of Grandpa’s friends (Cheung Hei, of The Black Butterfly and The Dragon Lives Again) is a sea captain, and he allows Tung to stow away aboard his ship when it sails for San Francisco a few days later. (Bet you were starting to wonder when we’d get there, huh?)

Tam Tung is one of two young men who soon find work washing dishes and bussing tables at the restaurant owned by a smarmy old Scrooge named Chen (Yung Chi-Ching, from Tales of a Eunuch and Vengeance!). The other is Taiwanese college student Yang Jian-Wei (Sun Chien, of The Five Deadly Venoms and Human Lanterns). Having served out his mandatory stint of military service (and learned a fair amount of tae kwon do while he was at it), Yang is now attending some bay-area university on an academic scholarship that covers all of his school expenses, but none of his living expenses. And since he’s in the US on a study visa rather than a work visa, he isn’t technically allowed to get a job. In other words, Yang, like Tam the undocumented stowaway, is the perfect sort of employee for a shady bastard like Chen, however big a show the restaurateur might initially make of not wanting to hire him. Chen then contrives to reduce both lads’ wages even further by putting them up in the loft above his restaurant, and deducting a no doubt extortionate amount for rent. Even so, Tam and Yang treat the whole thing like the realization of a dream neither one of them was quite conscious of having, and as the greatest adventure of their lives so far. And given their backgrounds in 1970’s East Asian poverty, the pittance Chen pays is enough to make both of them feel newly rich.

The trouble is that San Francisco’s Chinatown has triads of its own, running protection rackets on all the local businesses just like in the old country. The block where Chen’s restaurant stands is in disputed territory, claimed by both the Green Tiger mob, headquartered in the martial arts school run by Wong Fu (Lo Meng, from Invincible Shaolin and The Eternal Evil of Asia), and the White Dragon mob, based at a nightclub owned by Siu Bak-Lung (Phillip Kwok Chun-Fung, of Crippled Avengers and Master of the Flying Guillotine). There’s also a third triad boss sniffing around for opportunities to exploit the other gangs’ rivalry, by the name of Wang Mo (Tsai Hung, from The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers and The New Game of Death). Tam Tung bumbles right into the center of this conflict when he beats the stuffing out of a bunch of Green Tigers at the laundry where Chen gets all his linens washed. The dumb bastards had tried to collect their protection dues when Tung was on the premises flirting with the owner’s cute daughter, Yvonne Li Hua-Feng (Jenny Tseng, of The New Shaolin Boxers and The Avenging Eagle). At first, every gangster in town assumes that this formidable new player was imported by one of the opposing mobs. But once word gets out that Tam is really just the deadliest fresh-off-the-boat bumpkin in Chinatown, a stiff competition breaks out to secure his loyalties or to force his submission, whichever seems more feasible. Tung is too simple (both in his tastes and in his cognitive abilities) to be corruptible by ordinary means, however, and too pigheaded to submit to anyone. Neither approach is at all viable until Chen foolishly fires Tam and kicks him out of his loft for “causing trouble” by actually protecting the restaurant from the gangsters whom Chen pays for protection. Then the gangland struggle takes a personal turn for Tung when Tsui Ho arrives in San Francisco, looking to facilitate a consolidation of the various Chinatown factions on behalf of a shadowy triad overlord back home. Tam Tung fears no one, and wants nothing that it would take mob boss to give him, but he just might be enlisted as an ally of whomever has the balls to make enemies of Tsui Ho and the unseen man pulling his strings from abroad.

I said a couple times already that Tam Tung isn’t terribly bright, but it’s important that you understand the specific ways in which he isn’t. Tung is impossibly naïve, excessively trusting, and slow to catch on to the true nature of any situation in which he finds himself. He’s easily impressed by shiny objects, in both the literal and figurative senses of that phrase, but he has little concept of the cost or value of anything he covets. He seems incapable of devising or following through on any but the simplest of long-range plans, and mostly just acts on the impulse of the moment. But Tam’s lack of smarts, sophistication, and self-control is also presented as the root of his essential goodness. Excessive trust, after all, can be much the same thing as limitless personal loyalty. Liking material things with no grasp of their cost or value can translate into immense generosity. Impulsiveness and poor planning skills can manifest as a willingness to drop everything in favor of helping someone out of a jam, heedless of the inconvenience or even danger that might entail. Add it all up, and Tam Tung comes awfully close to fulfilling the old trope of the Holy Fool, like a kung-fu-fighting Forrest Gump!

For Chinese audiences of the 70’s, however, that “kid” in Chinatown Kid— originally jiao zi or siu ji, depending on whether you prefer the Mandarin reading or the Cantonese— was a clue to expect a very different archetype, which Tung also embodies almost in textbook fashion. Siu ji in Hong Kong cinema were a bit like the “slobs” in Hollywood’s “slobs vs. snobs” comedies of the same era. They were transgressors against order and authority, but in what was supposed to be a funny, lovable way— even when, strictly speaking, they were out and out criminals. Alexander Fu Sheng did a lot to define the type as pertains to martial arts movies with his portrayals of the Shaolin heroes Fang Shih-Yu and Ma Chao-Hsing, so he’s in familiar and presumably comfortable territory here. But when you combine the impish brashness of the siu ji with the slow-witted earnestness of the Holy Fool, a very strange alchemy occurs. Viewed in the round, so to speak, Tam Tung starts looking less like Forrest Gump, and more like The Jerk’s Navin R. Johnson. Come to think of it, Navin’s kung fu wasn’t half bad, either…

So now picture Navin R. Johnson as the “thug with a heart of gold” protagonist in a gangster movie that can’t quite decide how funny or serious it’s supposed to be, and you’ll have some idea why I found watching Chinatown Kid to be a confusing, frustrating experience. On the upside, Tam Tung being both a well-meaning dimwit and a rebel with no impulse control makes it halfway plausible for him to blunder his way into becoming a gangland power-player. It also makes him the one remotely convincing iteration I’ve ever seen of the mobster who draws a hard line at dealing drugs. Indeed, Tam draws a hard line at just about any premeditated crime— which would have made him a superbly entertaining central figure, had Chang Cheh gone all-in on treating Chinatown Kid as a comedy. I mean, “up-and-coming triad enforcer is incensed to learn that his criminal organization is committing crimes?” That’s a solid joke, with lots of room for inventive variations. But from the moment Tsui Ho re-enters the story, Chinatown Kid turns increasingly grim and bleak, even as Tam remains his old, goofy self. It’s one thing to say that your Holy Fool is also a siu ji, and gets thereby a pass for his clodhopping feet of clay, but something else again to show him hunting down his enemies and beating them to death, you know?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact