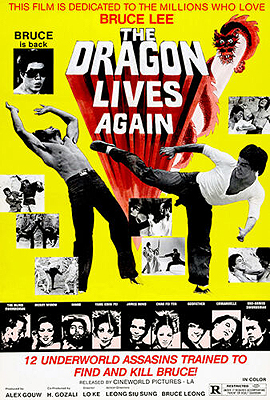

The Dragon Lives Again / Deadly Fists of Kung Fu / Li San Jiao Wei Zhen Di Yu Men (1977) -***½

The Dragon Lives Again / Deadly Fists of Kung Fu / Li San Jiao Wei Zhen Di Yu Men (1977) -***½

Bruce Lee picked a really shitty time to die. For one thing, he was only 32 years old. For another, The Big Boss, Way of the Dragon, and Fists of Fury had just made him the biggest martial arts movie star in Hong Kong. And as if that weren’t enough already, Enter the Dragon— which hadn’t even been released yet— was about to make him the biggest martial arts movie star in the world. Nor were Lee, his fans, and his loved ones the only people whom his death inconvenienced. The international success of Enter the Dragon initiated a kung fu craze in parts of the world that had just barely heard of the discipline previously, giving filmmakers in Hong Kong and Taiwan an unprecedented opportunity to break into lucrative markets overseas. Obviously Lee himself would have been a tremendous asset to any such endeavor (and indeed his earlier pictures were rushed into foreign release at considerable profit), but a dead star normally leaves limited options for future exploitation. There were the inevitable tributary documentaries, the inevitable biopic, and the inevitable crass pieces of shit built around outtakes and obscure bits of stock footage. But those predictable strategies didn’t begin to satisfy the demand for more Bruce Lee material, and that’s when things got weird.

Obviously what was really wanted was a replacement for the suddenly bankable yet also suddenly dead star. To some extent, that just meant a largely futile search for a successor, with every reasonably attractive young actor in the Sinosphere who could do a plausible high kick being evaluated for promotion as “the next Bruce Lee.” But it also meant every martial artist who bore the dead man even a passing resemblance being pressed hastily into service as a counterfeit Lee. Thus Huang Jian Long became Bruce Le. Ho Chung Tao became Bruce Li. Chang Yi Tao became Bruce Lai. Moon Kyeong-seok became alternately Bruce Lei and Dragon Lee. And so on, and so on, and so on and on and on. Not infrequently, these guys were called upon to play the real Bruce Lee, both in nominally nonfictional contexts and in films that posited Lee faking his death or returning from the grave or some other such openly fantastical nonsense. Eventually, enough of these movies got produced that it made sense to start thinking of them as a kind of meta-genre, and Brucesploitation was born. Conceptually speaking, The Dragon Lives Again is the screwiest Brucesploitaion flick that I know of. Rather than finding an excuse to bring Lee back to life, it follows him into the underworld of traditional Chinese cosmology, which he inexplicably finds populated with fictional characters from around the world, and where he runs afoul of a conspiracy by some of them to overthrow Yan Wang, the king and judge of the dead.

(That seems like as good a cue as any for this digression. As you might expect, a lot of conflicting traditions about Yan Wang have sprung up over the millennia, and it’s worth noting which one The Dragon Lives Again seems to favor. Some Chinese believe that Yan Wang is not a specific supernatural personage, but an office within the Celestial Bureaucracy which has been held by any number of incumbents throughout the ages. That includes even a few particularly worthy human spirits. Some sources identify The Dragon Lives Again’s Yan Wang as “Hades Judge Pao,” which suggests that we’re actually talking about Bao Zheng. A real 11th-century official renowned for the integrity with which he exercised his judicial authority, Bao Zheng is sometimes said to have been rewarded with the office of Yan Wang upon his death in 1062.)

The fake Bruce Lee here is Leung Siu Long, from Bless This House and The Clones of Bruce Lee, known during this phase of his career as Bruce Leong. So long as he keeps his sunglasses on, he isn’t a terrible facsimile. He’s far enough off the mark, though, that the filmmakers felt compelled to add a line of ass-covering dialogue explaining that a person’s manifestation in the afterlife needn’t necessarily look like their Earthly form. In any case, it comes as quite a surprise to Lee when he finds himself in the underworld, being examined and judged by Yan Wang (Tang Ching, of Swordsman and Enchantress and Slash: Blade of Death). Lee’s cocky attitude scandalizes the assembled grandees of the underworld court (incidentally, notice the two burly guys with the ox head and the horse head respectively; those are Ma Mien and Niu Tou, Yan Wang’s demon bailiffs), and he is given to understand that he will be watched very closely going forward. Yan Wang sees little choice but to let Lee keep his nunchaku, though, since neither he nor anyone on his staff has the strength or the speed to confiscate them successfully.

Lee proceeds to a nearby village (Bad Dog Village, perhaps?), where he gets a table at the local inn and orders lunch. It may take a while for it to click just who all these people are supposed to be, but among the regulars at this tavern are Kwai Chang Caine from the American TV show “Kung Fu” (San Kuai, from 36 Crazy Fists and We’re Going to Eat You) and Popeye the Sailor Man (Eric Tsang Chi Wai, of Enter the Fat Dragon and Vampire Family). No, really. Also having lunch at the inn when Lee sits down is Zatoichi the Blind Swordsman (Wong Mei, from Centipede Horror and The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires)— who, given typical Chinese attitudes toward their neighbors across the Sea of Japan, is naturally a more sinister figure than we’re accustomed to. Zatoichi is the most hands-on member of the underworld’s number-one criminal gang, involved in who knows how many schemes to separate the spirits of the dead from their Hell Money.

The first time Zatoichi tangles with Lee (because Bruce is a fucking hero— of course he’s going to pick a fight with the first mob enforcer he meets!), the newly dead man’s kung fu prowess takes the gangster sufficiently by surprise that he calls for backup in the form of about ten guys in skeleton leotards. We will later learn that these are zombies on loan from Count Dracula (Cheung Hei, of Hex and Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan), but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. While the zombies have Bruce distracted, Zatoichi is able to cast some sort of Jeet Kune Don’t spell on him, temporarily depriving him of his fighting skills; the blind swordsman strangely never uses that seemingly most helpful ability again. Regardless, the zombies pummel Lee, and Zatoichi withdraws, plausibly assuming that he’s taught the interloper a lesson.

Lee is taken in and nursed back to health by a beardy old man called Wa To (Simon Yuen Siu Tin, from Drunken Master and Mantis Fist Fighter) and his daughter (Sarina Sai Zhen Juan, of Bed for Day, Bed for Night and Mantis Fist and Tiger Claws of Shaolin). It’s possible that we’re supposed to recognize them, too, from somewhere, but I myself do not. His recuperation slows the movie down enough to accommodate a subplot in which Lee develops a crush on his pretty nurse, leading Yan Wang’s two favorite concubines (Terry Lau Wai Yue, from The Killer Snakes and Bamboo House of Dolls, and Goo Ming, of Girls for Sale and Kung Fu Means Fists, Strikes, and Swords) to impersonate her in the hope of seducing him for themselves. Bruce likes to be the one doing the chasing, though, so the infernal women’s ruse is unsuccessful.

Things get rolling again when Lee starts giving kung fu lessons in the village square, and using his influence as a moral exemplar to drive the local gambling den out of business. One of the habitual bettors whom he puts on the straight and narrow is Fang Kang the One-Armed Swordsman (Nick Cheung Lik, of 36 Deadly Styles and The Fatal Flying Guillotines), so you know that’s going to be important later. It has near-term consequences, too, insofar as it pisses off two crooked cops who supplement their wages by skimming off the casino’s revenues. Those clowns are no match for Lee and his increasingly formidable students, however.

Inevitably, the bent cops are ultimately beholden to the same cartel as Zatoichi, so let’s go meet the rest of the gang, shall we? The leader of the pack is a fellow they call the Godfather (Shil Il Lung, of Wind from the East and To Kill with Intrigue). I’m not convinced he’s supposed to be that Godfather, though; between his Fat Elvis pompadour, his glammed-out not-quite-a-Mao-suit, and his foppish cravats, I get more of a Sonny Chiba/Kinji Fukasaku vibe from him. Maybe somebody who knows more than I do about 70’s Asian crime films would be able to ID him more confidently. Handling the wet work in situations where guns are more helpful than swordplay and chopsocky are James Bond (Alexander Grand, from Fist of Unicorn and The Mighty Peking Man) and Sergio Leone’s Man With No Name (Bobby Canavarro, from The Lewd Woman and Confessions of a Private Secretary). Emmanuelle (a gwailo girl identified only as “Jenny”) fills the femme fatale slot. And last but not least, there’s Father Lancaster Merrin the exorcist (Fong Yao, of Killer in the Dark and Return of the One-Armed Swordsman). Merrin seems not to be part of the gang per se. I get the impression, rather, that the Godfather and his followers are helping him out because he’s the kind of guy whom you want to owe you favors. The exorcist’s ambition is nothing less than to overthrow Bao Zheng and usurp the role of Yan Wang! His plan is to finagle a place for Emmanuelle in the underworld king’s harem, so that she can literally fuck him to death. So far, Bruce Lee hasn’t posed a threat to that scheme, but he sure is troublesome for the gang’s regular business. The Godfather thinks it’s time something were done about him— and if Zatoichi can’t handle it (spoiler: he can’t), then Merrin is happy to call in his buddy Dracula with his zombie army.

Don’t ask me why, but when Dracula makes his unsuccessful bid to take down Lee, he’s carrying documents that explain the entirety of Father Merrin’s plan to make himself Yan Wang. Bruce goes at once to show the papers to Bao Zheng, and although the king is initially most displeased to have his coitus with Emmanuelle interrupted, he changes his tune once the exorcist’s plot is explained to him. (“Even her pussy is in on the conspiracy!” he gasps as the full ramifications sink in.) Bao sends the amorous assassin packing, and grants Lee a commission as his personal bodyguard— making him instantly the pivotal figure in the struggle for the throne of the underworld. But as Lee gradually discovers, Yan Wang’s commission also places him simultaneously on both sides of a second conflict. As the people of the underworld become more sure of themselves under Lee’s instruction and by Lee’s example, they start to think that maybe ridding themselves of the Godfather isn’t enough. After all, it can hardly be said that Bao Zheng has been living up to his royal responsibilities if a criminal mob has been left free to oppress them all these years.

I went into The Dragon Lives Again expecting to have my mind thoroughly blown, and perhaps the strangest thing about this movie is that it didn’t do that. There are two reasons why. First, it quickly becomes clear that The Dragon Lives Again was intended to be an absurdist comedy, which takes some of the bite out of its absurdities. Against the backdrop of a film industry that frequently does things 85% as loony as The Dragon Lives Again with a straight face, those extra 15% don’t have much impact when we know they’re meant in jest. That isn’t to say the jokes aren’t funny— a lot of them certainly are. My favorite gag was the “called shots” captioning during Lee’s showdown with Zatoichi, in which the blind swordsman counters Bruce’s “Fists of Fury” and “Enter the Dragon” techniques with kata like “Blind Dog Pisses.” (It’s a backwards-aimed kick from all fours, naturally.) Bruce Leong’s impersonation of Bruce Lee is funny, too, because it manages to be completely inaccurate and yet somehow also spot-on. It’s almost as if he’s doing a perfect impression of somebody else’s terrible Lee.

The other thing that makes The Dragon Lives Again somewhat less of a mindfuck than any description of it would naturally imply is that the skeleton of the story is remarkably conventional. You’ve definitely heard this one before: Stranger arrives in a place controlled by rival oppressors; he defeats the lesser oppressors on his own, then aids the downtrodden in overthrowing the greater. That isn’t just a stock kung fu plot; it’s also a stock chambara plot, a stock Western plot, a stock post-apocalypse plot, a stock peplum plot, a stock space opera plot, and who knows what else. It’s only when you start filling in the details that The Dragon Lives Again goes berserk.

I have to draw a distinction in this case, however, between saying that my expectations weren’t met and saying that I was disappointed. As I mentioned before, a fair amount of the humor genuinely works, and the sheer ridiculousness of the proceedings is enough to carry the movie over the gags that either fall flat or get lost in translation. The crappiness of Dracula’s zombie army, and of the similar army of mummies that shows up for the climax, is endearing in the usual no-budget way, as is the bizarre decision to teleport nearly every fight scene from its initial venue to the same rock quarry once things get violent enough to threaten the flimsy sets. The English-language dub, as usual, contributes to the fun, not only via eccentric combinations of phrasing and delivery, but also thanks to baffling touches like Father Merrin’s inexplicable French accent. (Emmanuelle, meanwhile, exhibits no trace of either of the European accents that one might expect the dub to attribute to her.) The fights are adequate, if unexceptional. What interest they have lies less in Leong’s moves than in the novelty of seeing (for example) a fake Clint Eastwood attempting to gunsling a fake Bruce Lee. Well, okay— there’s also something to be said for seeing an unexpectedly recognizable Chinese Popeye down a can of spinach to supercharge his kung fu. (One minor quibble with the latter moment, though: the accompanying musical cue is Popeye’s opening credits theme; the spinach fanfare is a completely different arrangement.) The charming abruptness of old-school chopsocky pacing is in full effect here, with both individual scenes and the movie as a whole beginning and ending exactly at the beginning and the end, sparing not a second for setup or resolution. And I’ve always been a sucker for films that dare to go out with a special effect of breathtaking inadequacy. The Dragon Lives Again’s parting shot may not quite equal Megaforce’s infamous flying motorcycle, but that’s the kind of thing we’re talking about here. I’m told that currently available home video editions of The Dragon Lives Again are pretty rough going, but the very existence of the cleaned-up print currently working its way around the revival theater circuit suggests that something better may be coming along soon.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact