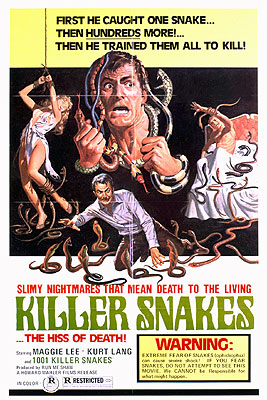

The Killer Snakes / The Sex Snakes / She Sha Shou / Se Sat Sau (1974/1975) **½

The Killer Snakes / The Sex Snakes / She Sha Shou / Se Sat Sau (1974/1975) **½

I always forget that Willard was kind of a big deal for a while. I suppose that’s partly because I’ve never seen the film myself (although I have read the source novel, Stephen Gilbert’s Ratman’s Notebooks, which deserves to be better remembered). But it might also be because so many of the ripoffs that were made during the mid-1970’s hybridized the core premise with those of other films whose reputations have had more staying power. Like maybe they’d make the bond between despised human and disfavored animal explicitly psychic, so that they functioned as knockoffs of Carrie as well. Or maybe they’d replace rats with a species that was a horror-movie star in its own right, like when Jaws of Death made its Willard analogue a friend to all sharks. In any case, The Killer Snakes makes for an especially striking reminder of Willard’s impact, because this Ratman ripoff was made in Hong Kong, of all places, by no less an outfit than the Shaw Brothers!

For this movie’s setup to make any kind of sense, it’s necessary to know that snake products figure so prominently in traditional Chinese medicine that some health-food restaurants serve literally nothing else. Serpents of various species are kept alive on the premises in cages or cabinets, and are butchered on the spot in whatever way the customer’s order calls for— and at least in the old days, the animals would sometimes be left maimed but still living if the needed body part was something that a snake can survive without long enough for another buyer to come along with a more necessarily fatal order. Gwan Fu-Cheng (Chow Gat, from Invincible Boxer and The Dragon Lives Again) maintains such an establishment in the marketplace of some Hong Kong slum that the original target audience for The Killer Snakes would probably have recognized. We meet Gwan as he’s serving up a cobra-bile cocktail to an oily would-be ladies’ man called Hu Bao-Chun (Richard Chen Chun, of The Adulteress and A Haunted House) and his vocally reluctant date. Gwan has been doing this long enough to know just where a snake keeps its gall bladder, so he’s able to perform a minimally invasive extraction preserving the rest of the cobra for whomever might want something done with its skin or meat or liver or whatever. The wounded snake goes back into the cell in the cabinet where it came from, and Gwan never thinks any more about it.

What the proprietor of the snake shop doesn’t realize, however, is that the wall into which his bureau full of serpents is built is not very secure from the other side. The injured cobra is able to find an escape route through the ill-maintained lathing into the abandoned and boarded-up stall next door. No, wait— make that officially abandoned. Although nobody’s using the stall for its intended purpose, the place is being squatted by a young man by the name of Chen Chih-Hung (Kam Kwok-Leung, from Wonder Women and Rivals of Kung Fu). We’ll have to watch a bunch of flashbacks in order to put all this together, but Chen ran away from home when he was just a boy. That’s because his dad was an abusive brute, while his mom was a perverted masochist, and growing up the way he did has left him socially stunted, wracked with resentments and insecurities, and riddled with high-grade sexual neuroses of his own. He’s also dirt poor, has no friends, and gets preyed on pretty much everywhere he goes by everyone even slightly “superior” to him on any conventional scale of social measurement. Chen has always had a thing for snakes, though, so when he sees that his lair has been infiltrated by a cobra with part of its guts hanging out, he takes pity on the creature instead of looking for some weapon with which to finish the job. Chih-Hung gently and fearlessly catches the snake, stitches up the gash in its flank with his sewing kit, and then builds a nice, warm nest for it by stuffing a cardboard box with moth-eaten blankets. He even gives it a name: Lu Pao. And from that moment forward, Chen has at least one friend after all.

Maybe there’s such a thing as karma, too, because shortly after rescuing the cobra, Chih-Hung enjoys a twofold upturn in his circumstances. First, he gets hired as a delivery boy by a restaurateur (Chu Gam, from A Taste of Cold Steel and Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan) elsewhere in the marketplace. I don’t know enough about prices or wages in 1970’s Hong Kong to determine how good a job it is, but since a squatter’s rent is approximately HK$0 per month, the money definitely stretches much further for Chen than it would for somebody leading a more above-ground lifestyle. Better yet, now that he has cash in his pocket, Chih-Hung feels emboldened to act on a feeling that he’s been developing for some time. There’s a fabric vendor across the street from the stall where he lives, you see, and the hawker there is a cute girl called Xiao Chuan (Maggie Li Lin-Lin, of Lightning Sword and Fairy, Ghost, Vixen). Chen is awkward and hesitant about asking her out, but evidently she sees something in him despite everything, because he goes away with a date for a midnight movie. Unless I miss my guess, it’ll be the first such outing Chen has ever been on in his life. Finally, before turning in for the night, Chih-Hung does another good deed for Lu Pao, helping him lead all the other snakes from Gwan’s store to freedom and safety on his side of the communicating wall. Gwan himself is understandably baffled when he opens up in the morning to discover that all his merchandise has somehow disappeared.

Or then again, maybe Chen’s sudden run of good luck was just a fluke, because it doesn’t take long for his usual pattern of getting it right in the jimmy from life, the universe, and everything to reestablish itself. First, Chih-Hung gets mugged by a pair of goons (Ko Hung, of All Men Are Brothers and The Oily Maniac, and Li Min-Lang, from The Eight Immortals and Calamity of Snakes) after making a delivery to the whorehouse where Zhang Jin-Yang (Helen Ko Ti-Han, from Black Magic and The Snake Prince) plies her trade. His boss fires him on the spot, too, when he returns from the delivery not just unacceptably late (getting robbed can be surprisingly time-consuming), but without any money to show for it, either. Meanwhile, Xiao Chuan’s father (Hao Li-Jen, of The Seven Coffins and The 36th Chamber of Shaolin) falls gravely ill, so that she has to skip out on her date with Chen to rush him to the hospital. Chih-Hung has no way of knowing that, of course, so he plausibly infers that he’s been stood up when closing time at the movie theater rolls around without any sign of the girl whatsoever. What Chen does in response tells us pretty much everything we’ll ever need to know about his emotions and how he handles them. Seething with impotent fury, he goes straight to Xiao Chuan’s stall in the market, and trashes it. Then, overcome with remorse, he pitifully and ineffectually attempts to repair the damage, and sits down on a deserted street corner to tell Lu Pao all about his latest shitty day.

As that last bit ought to imply, now that Lu Pao is in as good health as it’s possible for a snake without a gall bladder to be, Chen has taken to carrying the cobra around with him, concealed somehow or other within the tattered layers of his clothes. That comes in very handy a night or two later, when he decides that he absolutely must get laid posthaste, and goes to hire Jin-Yang. Turns out it was no coincidence that those hoodlums who robbed him before were hanging around the brothel. They’re Jin-Yang’s security, and the hooker leads them out after Chen for a repeat performance almost as soon as their mutually unsatisfactory transaction is concluded. Jin-Yang and her boys hadn’t figured on Lu Pao, though. This second mugging is cut short when the snake slithers out of its human’s shirt to enter the fray. Jin-Yang faints dead away upon seeing her thugs go down foaming at the mouth, at which point Chen gets a wicked idea into his head. When Jin-Yang comes to, she’s in her intended victim’s lair, naked, gagged, and tied up in the manner of the Japanese rope-bondage porn that Chih-Hung favors. Although her captor is no better at maintaining an erection now than he was at her place, this time there are quite a few long, cylindrical columns of flesh on hand that will be perfectly willing to act as a surrogate if Chen wants them to. And if Jin-Yang should happen not to survive being snake-fucked, well, that’s actually pretty convenient for Chen when you really think about it.

Now all this time, Chen has been liberating Gwan Fu-Cheng’s snakes as fast as he can restock them, and the increasingly exasperated shopkeeper finally gets the big lightbulb to check the ostensibly empty storefront next to his while Chih-Hung is pondering how to dispose of the hooker’s body. Obviously Gwan will have to go now, too, but from that necessity arises a neat solution to Chen’s preexisting problem. He just dumps both corpses next door, so that when they’re discovered the following day, it looks like Gwan hired Jin-Yang for a tryst at his shop, then got caught with his pants around his ankles when all his snakes unaccountably escaped from their confinement. That’s a weird enough set of circumstances to attract a more thorough official investigation than Chen would like, obviously, but at least it doesn’t specifically implicate him.

As for Xiao Chuan, her dad doesn’t last long even with medical attention, and the hospital and funeral expenses between them gobble up most of what little money the family had saved up. Xiao Chuan’s income from the fabric stall isn’t nearly enough for her to live on by itself, and she doesn’t even have the ready cash to pay next week’s rent. Fortunately her friend, Fang Fang (Terry Lau Wei-Yue, from Revenge of the Zombies and Infra-Man) has a way out of her fix. Fang Fang is a hostess at an upscale bar called the Vault, in which profession she makes lots and lots of money. As pretty and charming as Xiao Chuan is, she ought to be comparably successful. Mind you, Fang Fang doesn’t mention that she also turns tricks for her landlady (who apparently also owns the bar), or that her bar-hostess gig is essentially a system for recruiting and vetting her sex-work clientele. Nothing about Xiao Chuan’s new arrangement requires her to become a prostitute as well, but if she’s following the money at the Vault, that’s where it leads. By an interesting coincidence, one of the Vault’s regulars— in all of its capacities— is Hu Bao-Chung, the guy whose cobra-bile tonic shot set this story in motion. Lately he’s been after the proprietress to find him a virgin to deflower— and I’m sure that has nothing to do with how eager she was to hire Xiao Chuan, right? Anyway, when Xiao Chuan packs up her stall and moves out of the market, gossip quickly spreads among the remaining shopkeepers about her change of profession. I bet you can guess how far off the deep end Chen goes when the barber down the street (Wong Ching-Ho, of The 8 Diagram Pole Fighter and Human Lanterns) tells him that the girl he so yearned for has become a whore like Jin-Yang, even if that isn’t precisely true yet.

The extraordinary thing about The Killer Snakes is what an absolute creep Chen Chih-Hung is. Most Willard knockoffs that I’m acquainted with try to make their animal-commanding protagonists at least as sympathetic as Carrie White, even if they’re not likeable in any ordinary sense. And in Ratman’s Notebooks, the character who wasn’t yet called Willard is relatively harmless until the boss he’s always hated kills his favorite rat. This guy, though… At first I was inclined to cut Chen some slack on account of his thoroughly miserable background. Bad parents, no friends, no money, no decent place to live— who wouldn’t turn into kind of a jerk with all that going against them, simply in a spirit of self defense? And of course there’s bound to be a rush of “Yeah! That’ll show ’em!” catharsis when Lu Pao turns the tables on the muggers that second time. But when a fellow’s first conscious act as Master of Serpents is to use that power to commit premeditated rape and murder, we’re obviously dealing with a whole ’nother breed of asshole! On a personal level, then, Chen is less Willard than Travis Bickle— which is doubly interesting because The Killer Snakes came out two whole years before Taxi Driver. It’s enough to make me wonder if there might be a whole cycle of 1970’s Old Dirty Hong Kong movies, the way Old Dirty New York is a recognizable meta-genre in American exploitation cinema.

Regardless of whether it’s part of some analogous tradition, though, The Killer Snakes should certainly appeal to fans of Times Square grindhouse fare, and on essentially the same level. It has a similar lowlife ambience, a comparably misanthropic outlook, and very much the same unbridled determination to shock and offend. Even its warped sense of humor lies along familiar lines, which my admittedly limited experience suggests is unusual for a Hong Kong film. There is a rather serious downside, however. Because this is an Asian trash flick from the 70’s involving lots of animals, it follows with all the inevitability of Newton’s Laws of Motion that the animals in question were treated abominably throughout. I mean, Lu Pao’s onscreen gall bladder extraction is about the least awful thing to happen to a snake in this film, so brace yourself for that if you decide to give The Killer Snakes a try.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact