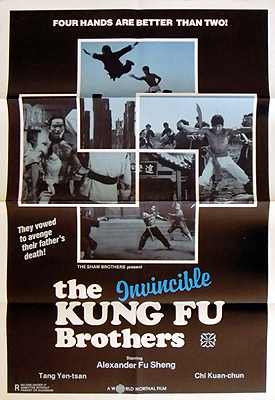

The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers / The Shaolin Avengers /Fang Shi Yu yu Hu Hui Qian (1976) **Ĺ

The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers / The Shaolin Avengers /Fang Shi Yu yu Hu Hui Qian (1976) **Ĺ

I wasnít the only one who found Men from the Monastery to be the least satisfactory of the three films that Chang Cheh made in 1974 dramatizing the legends of the Shaolin Temple. Audiences in Hong Kong didnít take to it as warmly as they did to Heroes Two or Five Shaolin Masters, either, so that both of the latter movies significantly out-grossed the other at the domestic box office. And more notably, Chang himself might not have been altogether content with the results of his second Shaolin Temple film, because when he returned to the series in 1976, he began with what was essentially a do-over. The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers retells the origin stories of Fang Shih-Yu and Hu Huei-Chien (or Fong Sai-Yuk and Hu Hui-Guan, depending on which reading of their names you prefer) in greater depth and detail than in the previous film, making room by skipping over Hung Hsi-Kwan and sidestepping the destruction of the temple. But although this movie covers most of the same exploits from the two heroesí careers, it puts a sufficiently different spin on them to preclude once again any possibility of establishing a single coherent continuity for the series. Alas, that may not be quite the same thing as a sufficiently different spin to make both versions worth watching, even if either one is more or less as good as the other.

The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers begins in the thick of things, with Fang Shih-Yu and Hu Huei-Chien (Alexander Fu Sheng and Chih Kuan-Chun, both reprising their Men from the Monastery roles) on the run through the countryside around Guangzhou, pursued by a horde of fighters from the Jun Lin kung fu school, led in person by its sifu, Feng Dao-De. (Oddly, although the actors playing the heroes have returned to their former roles, all the named villains whom this movie shares with its predecessor have been recast. The new Feng Dao-De is Tsai Hung, from The Silver Spear and Revolt of Kung Fu Lee.) There are two other characters involved here whom weíve never seen before, however. One of them is Fangís hitherto unmentioned older brother, Fang Xiao-Yu (Bruce Tong Yin-Chaan, of The Deadly Quest and Bruce Leís Greatest Revenge), who has been fighting by Shih-Yuís side since the very beginning in this version of events. The other is Pai Mei (Chen Hui-Lou, from Bruce Lee vs. Frankenstein and Tiger and Crane Fists)ó or Bak Mei, in the Cantonese readingó the White-Browed Priest. He sort of put in an appearance in Men from the Monastery, but only as an ominous shadow cast on the temple wall while he gave instructions to his spies among the brothers. This movie is much clearer not only about Pai Meiís identity, but also about his role as the grandmaster of the Wu Tang Clan, arch-enemy of Shaolin disciples everywhere. You might therefore expect him to take an active role in the battle to come, but in fact heís been following along at a distance so far, seemingly content to leave the hands-on work to Feng Dao-De. Also, it soon becomes apparent that Chang and co-writer Ni Kuang have brought us in mere minutes from the end of the story. This fight is the final showdown between Shaolin and Wu Tang, and as it progresses, each shift in the fortunes of either side triggers a thematically relevant flashback explaining some piece of how we got here.

For instance, do you know how the Fang brothers got into the kung fu business in the first place? Turns out their parents were both renowned martial artists in their own rights. Mother Miao Cui-Hua (Ma Chi-Chun, from One-Armed Knight and Snake Womanís Marriage) was a disciple of the famous Shaolin abbess Wu Mei, while father Fang Ji-Heng (Weng Hsiao-Hu, of 18 Swirling Riders and Killer from Above) was a notable defender of the downtrodden. Fang the Elder bit off more than he could chew, though, when he took on Lei Lau-Hu (Lung Fei, from Shaolin Kung Fu Mystagogue and The Ghost Hill), a rat-bastard who had been using his fight club in Guangzhou as a mechanism for eliminating those who would stand up for the oppressed on his turf. Ji-Heng was treacherously killed when he went to challenge Lei, and found himself fighting his only slightly less fearsome sidekicks, Peng Bu-Yin (Leung Kar-Yan, of Shaolin Martial Arts and Warriors Two) and Yuan Nan (Jamie Luk Kim-Ming, from The Brave Archer and Five Shaolin Masters), as well. The brothers swore themselves to vengeance before their mother, but Cui-Hua understood that they were in no way ready to take on such a task. Fortunately, Mom had a trick up her sleeve that Lei and his followers would never see coming: the old abbess entrusted her with the secret to rendering the human body impervious to any form of outward attack. Of course, a thing like that must have a downside, or else everyone would do it. For starters, Wu Meiís invulnerability treatment works only on virgins, and anyone who undergoes the process must remain a virgin thereafter. Also, the regimen itself is literal torture, involving severe floggings alternated with soaking in a heated cauldron of rice wine mulled with rare medicinal herbs, whose effects on human flesh are no less painful than the whipís. Cui-Hua had raised two good Confucian boys, though, so suffering was no deterrent when a chance to avenge their dad was on the line. Granted, the virginity requirement took Xiao-Yu, already married and a father, out of the running, but since it would fall to him to administer Shih-Yuís beatings, and to keep his beloved brother imprisoned in that tub of doctored wine, the undertaking wound up costing him plenty, as well. The ordeal was well worth it, however, as was proven by the quick work the Fang boys made of Peng and Yuan at Leiís fight club once it was all over.

Another new thing we learn in the flashbacks is that the battle between Fang Shih-Yu and Lei Lau-Hu atop the grid of poles was the climax to a tale much more involved than weíd previously been led to believe. As if Leiís role in Fang Ji-Hengís murder werenít enough to redefine his significance for the Fang brothers by itself, weíre now told that Lei responded to the deaths of his lieutenants by borrowing a posse of Wu Tang fighters from Feng Dao-De for a strike on the familyís home. When it turned out the boys were out of the house somewhere, Lei consoled himself by killing Miao Cui-Hua in their place. Thereís a lacuna in the back-story at this point, which I think is meant to elide the brothersí course of study at the Shaolin Temple, and then itís back to the old quest for vengeance, and ultimately the pole grid. The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers has it that the latter contrivance was not a regular part of Leiís dueling shtick, but rather an innovative response to the prospect of fighting an opponent deadly enough to have taken down Peng and Yuan. This retelling also acknowledges more directly that the panji stakes set into the ground among the poles were a complication uniquely well suited to exploit Fang Shih-Yuís sole weakness: because his body is invulnerable only to external attack, a sharp object rammed up his ass with sufficient force is just as deadly to him as it would be to the next guy.

The third and final set of flashbacks recapitulates Hu Huei-Chienís one-man war against a pair of gangsters affiliated with the Jun Lin school, presenting it much as Men from the Monastery did. Huís father (The Savage 5ís Lu Ti, who was in Men from the Monastery, but played a different character there) was murdered by crooked gamblers Lu Yin-Bu (Johnny Wang Lung-Wei, of Coward Bastard and Chinatown Kid) and Niu Hua-Jiao (Shen Mao, from One-Armed Boxer and Dog King and Snake King), but was denied justice when the equally corrupt gendarmes implausibly ruled his death a suicide. The younger Hu swore revenge, but that was easier said than done. After months of repeated ass-kickings by Lu and Niu (the fact that the gamblers always let him escape with his life goes to show how inconsequential a threat they deemed him), Hu was befriended by Fang Shih-Yu, who sent him to the Shaolin Temple to acquire the power and skill to match his moxie. Following his graduation, Hu returned to Guangzhou, and destroyed the textile mill that provided Lu and Niu with their substantial income, while Fang kept the gamblers busy by cleaning them out at dominoes in their own lair. That, at long last, convinced Lu and Niu that Hu was someone to take seriously, but the Shaolin monks had made him more than a match for themó especially with Fang Shih-Yu to back him up. But what Hu failed to recognize was that the gamblersí mill didnít just fill their own pockets. It also financed the Jun Lin school, where they had honed their own fighting abilities alongside the enemies of the Fang brothers. An attack on the mill is thus an attack on the school, and on Master Feng Dao-De as well. To pick a fight with Feng Dao-De, meanwhile, is tantamount to picking one with the Wu Tang Clan, which is not what most would consider a terribly clever thing to do. Thatís how the three Shaolin avengers find themselves where they are now, hunted across the province, outnumbered eleventy-to-one, and under observation by Pai Mei himself, just in case they prove too big a nuisance for even Feng and his mob to handle.

The central frustration of The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers is that Chang and Ni have chosen exactly the wrong material to recap from Men from the Monastery for the second half. The segment showing the rise of Hu Huei-Chien and his partnership with Fang Shih-Yu was easily the best part of the earlier film, and stood to benefit least from an expanded treatment. And indeed in a host of small ways, this new version of that story is inferior to the old, even without factoring in the diminishing effect of the repetition itself. I especially object to the way Fang Shih-Yu runs interference for Huís raid on the mill this time around. Although I suppose itís more realistic to hang that diversion on something that actually matters to the two gamblers, it was much more entertaining to see them bewildered into inaction by this arrogant kid strolling into their clubhouse to annoy them for no reason that they could discern. Also, itís maybe a bridge too far to portray Fang as a master domino-player as well as a superhero of kung fu. But who knows? Iíve never read Evergreen, the Qing-era novel that codified a lot of the Shaolin Temple legends in much the same way as Sir Thomas Malloryís Le Morte díArthur codified the legends of Camelot, so maybe thatís how it was ďsupposedĒ to go down.

On the upside, the flashback-heavy structure of The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers is a double asset, first because itís something I havenít seen before in a martial arts movie, and second because it somehow obviates what Iíd found to be a major stumbling block in Men from the Monastery, the wild imbalance between action and story. I donít really know how to account for the latter effect. It isnít as though The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers is paced any less breathlessly than its predecessor, after all, nor is it any less loaded down with hair-trigger fight scenes. Maybe itís simply that by starting at the climax, and back-filling how we got there whenever each particular bit of the story becomes relevant, this movie is able to connect the dots throughout in a way that the other didnít even attempt until close to the end. There may be no more downtime in The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers than there was in Men from the Monastery, but at least we always fully understand the stakes of any given clash.

My other major source of dissatisfaction with Men from the Monastery was how little attention it devoted to explaining the rivalry between Shaolin and Wu Tang. For the intended audience back home in Hong Kong, I expect that was no problem, but my uninformed gwailo ass could have used some coaching. The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers provides some at last. This movie posits that the two schools, philosophically opposed to begin with, were turned against each other by the Qing government in an attempt to neutralize the threat posed by Han Chinese martial artists in general. So long as Shaolin and Wu Tang are fighting each other, the power of either to oppose the Manchu takeover of China is critically diminished. Obviously I have no way of knowing whether thatís correct in terms of the original legendary narrative, but it makes sound psychological and political sense, especially in a context where ďcorrectnessĒ is as slippery as it seems to be here. Thatís a big part of the reason why I canít confidently dismiss either version of this story as the skippable one, even if watching both will inevitably feel a little like a waste of time. Men from the Monastery and The Invincible Kung Fu Brothers each have something important that the other lacks, so that youíll genuinely be missing out either way if you limit yourself to watching just one.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact