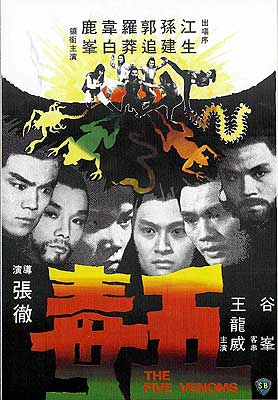

The Five Deadly Venoms / The Five Venoms / Wu Du / Ng Duk (1978/1979) ***Ĺ

The Five Deadly Venoms / The Five Venoms / Wu Du / Ng Duk (1978/1979) ***Ĺ

If youíve been following along with me on my voyage of kung fu discovery since December of 2022, you might have noticed certain names cropping up again and again. Director Chang Cheh, of course. Screenwriter Ni Kuang even more so. And most importantly for my present purposes, a quartet of actors: Alexander Fu Sheng, David Chiang Da-Wei, Chen Kuan-Tai, and Ti Lung. Those latter guys were known back home as the Four Pillars of Shaw Brothers, although Western fans have inevitably dubbed them the Fantastic Four as well. Whether singly, in pairs, or occasionally en masse, the Four Pillars were guaranteed draws at the Hong Kong box office throughout the early-to-mid-1970ís. Sir Run Run Shaw ran his studio very much on the model of Golden Age Hollywood, and he treated his stars the way Jack Warner, Louis B. Mayer, and Carl Laemmle Jr. had, both for better and for worse. More than just about anything, Shaw valued the attractive power of a proven lead actor, and he made sure his pictures were cast accordingly. Although he was always on the lookout for fresh talent, he preferred to have at least one instantly recognizable face on every movie poster, too.

Chang Cheh was therefore bucking well-established company policy when he proposed, early in 1978, to build a film around an ensemble of virtual unknowns instead. To be sure, all six of the men Chang had in mind were strong prospects. Two were accomplished acrobats; one was a practitioner of tae kwon do; four had trained at Taipeiís Fu Sheng Opera, which was functionally equivalent to training at the better-known Peking Opera schools on the mainland or in Hong Kong. Even the one who came to Changís attention as the accountant for his Taiwan-based satellite production firm had been studying Southern Praying Mantis kung fu since he was fifteen years old! And all of them had played supporting roles of various sizes in this or that Shaw Brothers picture during the past few years. But even so, itís doubtful that Shaw would have taken the risk had any director of lesser standing suggested it. Chang, it turned out, knew what he was doing, and The Five Deadly Venoms made stars out of all six of its lead performers. It was a new and strange form of stardom that the ďVenom MobĒ acquired, however, for it didnít seem to adhere to any of them individually. For the next four years, any film featuring three or more Venoms would make good money, but would-be solo showcases for any of them? Not so much.

The sifu (Dick Wei, from The Avenging Eagle and The Seventh Curse) of a clandestine kung fu school called the House of Venom is old and sick, and knows that he isnít long for this Earth. He has trained no successor as such, for his conscience is haunted by the evil for which his organization has been responsible over the years, and he intends for the House of Venom to die with him. Nevertheless, the old man does have one last discipleó a kid by the name of Yang De (Chiang Sheng, of Shaolin Temple and Masked Avengers)ó who has an important role to play in the sifuís post-mortem plans. First off, in order to make amends for the House of Venomís collective crimes, Yang is supposed to donate to charity the considerable treasure which the school has amassed. Mind you, thatíll be harder than it sounds, because the old master doesnít actually have the loot in his possession. When his former right-hand man retired some years ago, he took the whole kit and caboodle with him, and no one has seen him or it since. So Yang has some detective work ahead of him right up front. But of at least equal importance is the matter of Yang Deís predecessors. Before deciding to pull the plug on the House of Venom, the sifu trained five men to an extremely high level of proficiency in one each of the five fighting styles developed by the school: Snake, Gecko, Centipede, Toad, and Scorpion. (Yes, youíre quite right. Only three of those animals are even potentially venomous, although some frogs and toads do produce toxic skin secretions.) Yangís other mission is to find those five men (all of them now living incognito under assumed names, as is the way of the House of Venom, and unknown even to each other, due to the schoolís tradition of having its students train masked), and to eliminate whichever of them have yielded to the siren song of evil. Now Yang De was trained in the rudiments of all five Venom styles, but heíd be no match for any of the senior pupils one-on-one. Heíll therefore have to join forces with the good ones in order to take down their wicked brothers. Iím not sure what heís supposed to do if theyíve all gone bad; presumably heís just fucked in that case.

One thing that might make Yang Deís task a little easier is that the five Venom fighters all know about the missing treasure; thereís an excellent chance that theyíre looking for the retired sub-sifu too. And sure enough, all six parties eventually wind up in the same provincial capital, for essentially the same reason. It would be more accurate, however, to speak of four parties, for the three most corrupt Venoms have discovered each other, and teamed up. Li Dong the Snake (Wai Pak, of The Mad Monk Strikes Again and The Phantom Killer) and Zhang Yiao-Tian the Centipede (Lu Feng, from The Nine Demons and Legend of the Fox), now calling themselves ďHong Wen-TongĒ and ďTan Shan-HuĒ respectively, are acting as agents for Gao Ji the Scorpion, whose cover identity remains unknown even to his two accomplices. ďHongĒ is a prosperous merchant, so far as the rest of the world is concerned, and from his perch high up in societyís canopy, he thinks heís spotted the former number-two man at the House of Venom, leading a quiet, respectable life as Mr. Yuan (Ku Feng, of The Mighty Peking Man and The Boxer from Shantung), the provincial governorís accountant. However, when Hong and Tan invade Yuanís home one night in order to extort the loot out of him, he remains tight-lipped even under torture. The kung fu criminals vent their frustration not only by killing him, but by massacring his entire household as well. They arenít observant enough to recognize that the old man dies pointing the way to his treasure map, but the Scorpion is when he sneaks into the house to survey the aftermath later.

Governor Wang (Johnny Wang Lung-Wei, from Full Moon Scimitar and Dirty Ho), unsurprisingly, is extremely upset about the murder of his accountant. He gives the men of his gendarmerie just ten days to find the culprits, or itíll be canings for the lot of them. Captain Ma (Sun Chien, of Chinatown Kid and House of Traps) is rather bummed about that, but unbeknownst to him, Lieutenant He (Phillip Kwok Chun Fung, from The Brave Archer and Invincible Shaolin) has a leg up on most of the other cops in cracking this particular case. Thatís because He is really Meng Tian-Xia the Gecko. He immediately recognizes the crime as a House of Venom job, and since he too had fingered Yuan as the likeliest candidate to be the old sifuís vanished sidekick, heís pretty sure he knows the motive as well. The lieutenant asks to be relieved of his regular duties, so that he can devote himself utterly to ferreting out the killers, and Ma grants his request with only a momentís hesitation. Heíll have some unexpected help, too, because his own assumed identity has been cracked by Liang Shen the Toad (Lo Meng, of Shaolin Rescuers and Bastard Swordsman)ó or Li Hao, as heís calling himself nowadays. Li too is still on the straight-and-narrow (or as straight and narrow as anyone from the House of Venom can be), and he knows the crucial fact that the Snake and the Centipede are taking their marching orders from the Scorpion.

Meanwhile, Yang De has acquired a piece of the puzzle that none of the other people investigating the Yuan massacre possess. The Snake and the Centipede missed a servant when they exterminated their principal victimís household, and this manó Men-Fa (Lau Fong-Sai, from The Flag of Iron and The Kid with the Golden Arm) is his nameó saw the culprits fleeing the scene of the crime clearly enough to identify Tan Shan-Hu. And since Yang De has by this point figured out that Li Hao is the Toad, he can see to it that Men-Faís testimony makes its way to Heís ears, even if the cowardly menial himself would rather keep his mouth shut. The lieutenant gets a description of the Centipede by promising Men-Fa the protection of the palace dungeon until the trial is over, and then he, Li, and a squad of gendarmes lay an ambush that results in the killerís capture.

The Snake is much cleverer than his partner, however, and quickly devises a way to sabotage the court proceedings against Tan. Hong Wen-Tong wields some obscure form of undue influence over Governor Wang, and itís a trivial matter to convince him to turn a blind eye while the Snake bribes a crooked cop called Lin Guang (Suen Shu-Pei, from The Secret Shaolin Kung Fu and Buddhaís Palm & Dragon Fist) to suborn new, perjured testimony from Men-Fa, laying the blame on Li Hao instead. Lieutenant He would never stand for that, of course, but one never knows when, say, an urgent letter to the imperial capital might need to be sentó something requiring the personal attention of the governorís most trustworthy gendarme, you know? Then with He out of the way, itíll be much easier to misalign the wheels of justice so that they grind whichever way Wang (and more to the point, Hong) pleasesÖ

I think maybe I like Chang Cheh best when heís building martial arts movies on foundations repurposed from Occidental genres that arenít obviously compatible with kung fu or wuxia. Having already used crime melodrama, film noir, and Spaghetti Western elements to underpin his films, he now serves up a kung fu murder mystery, which is not something that Iíd even imagined existing up to now. The Five Deadly Venoms makes for Changís niftiest genre mashup yet, since the two sets of conventions have to twist themselves into truly strange shapes to accommodate each other. Like, Iím well accustomed to seeing policemen ally themselves with private investigators in order to take advantage of the latterís special abilities and/or freedom to disregard departmental procedure, but the unique talent that Li Hao brings to Heís Centipede trap is the invulnerability to physical attack that Toad Venom kung fu confers. Iím used to seeing crooked authorities torture bogus confessions out of framed suspects, but it changes the picture drastically if the villains must spend time figuring out how to render their preferred patsy susceptible to torture in the first place. And from the opposite angle, the ticking clock for Li Haoís rigged trial precludes Yang De from leveling up his fighting skills with a second-act training montage. The kidís just going to have to accept being outclassed, and trust Gecko He to have his back when he inevitably gets into trouble.

Thereís something interesting going on here in the fighting itself, which will come clearly into focus if we consider The Five Deadly Venoms in tandem with The Boxer from Shantung and Five Shaolin Masters. In The Boxer from Shantung, the oldest of the three films, what we see in the fight scenes is sort of a generic simulation of kung fu, despite the presence of at least two accomplished martial artists on the choreography team. That was the usual practice for Hong Kong martial arts films in the early 70ís, carried over from Chinese opera. Then in Five Shaolin Masters two years later, we see the full fruition of action director Lau Kar-Leungís quest to turn kung fu cinema into a showcase for authentic Southern Chinese fighting arts. Whereas before the movies treated kung fu as pretty much just kung fu, Lau helped usher in a new paradigm in which the differences between Hung Gar and Wing Chun, Five Animals and Five Elements, Shaolin and Wu Tang would become crucial to the narrative, and in which the performers would receive sufficient training in their charactersí fighting styles to convince an informed audience (if perhaps not an expert one). And now in The Five Deadly Venoms, something new emerges once again. Although this movie is as focused on matters of form and technique as any Shaolin Temple film, the forms themselves are synthetic, impractical, and in some cases literally impossible without recourse to special effects. When Ni Kuang and Chang Cheh say that Hong Wen-Tong is a master of the Snake style, they donít mean the real-world Snake Fist that figures so prominently in the Shaolin Temple cycle, but rather some fantastical bullshit that looks impressive on film, but is probably just a really good way to break your fingers. My understanding is that wuxia movies had been treating the martial arts this way for some time by 1978, but it was a real novelty on the kung fu side of the line. It also became a noticeable trend throughout the late 70ís and early 80ís, although it never superseded the Lau approach the way the Lau approach superseded the practices borrowed from Chinese opera. What Iím not clear on yet is whether The Five Deadly Venoms should be taken as the moment of innovation, or merely as a noteworthy early example. In any case, I canít deny that itís exciting to watch here, even if I do like Lauís way better.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact