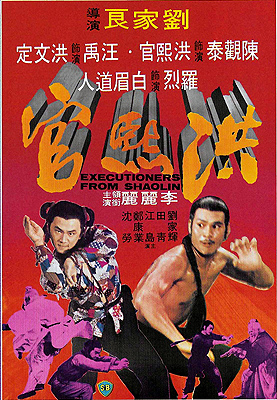

Executioners from Shaolin / Executioners of Death / Shaolin Executioners / Hong Xiguan / Hung Hei-Gun (1977) **

Executioners from Shaolin / Executioners of Death / Shaolin Executioners / Hong Xiguan / Hung Hei-Gun (1977) **

Before Lau Kar-Leung put his own distinctive stamp on the legends of the Shaolin Temple with The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, he brought something like closure to Chang Chehís original Shaolin cycle with Executioners from Shaolin. Even here, though, Lau already shows his eagerness to do something different with the material. Uniquely among the films in the series, Executioners from Shaolin is only fleetingly concerned with the immediate aftermath of the templeís destruction, and it encompasses a great deal more time than any of its predecessorsó something on the order of twenty years! Furthermore, although Ni Kuang has returned once again to write the screenplay, this movie seems to reflect Lauís conceptual priorities as a martial artist in its story as well as in its handling of the action. Although Ni and Lau do devote the first act to Hung Hsi-Kwanís post-Shaolin career as a rebel leader, the emphasis this time is on Hungís legendary roles as the originator of Hung Gar kung fu and a curator of the Shaolin tradition. And in keeping with that focus, it takes a substantially different view of the templeís downfall, treating Wu Tang sifu Pai Mei as the senior partner in the alliance between Shaolinís Martial World rivals and the Qing government.

Executioners from Shaolin signals that shift right up front by beginning not with the sacking of the temple per se, but with an extremely abstract and stylized depiction of one event within it: the duel to the death between Abbot Zhi Shan (Lu Hoi-Sang, of Invincible Armor and Dirty Tiger, Crazy Frog) and Pai Mei, the White-Browed Priest (played this time around by Lo Lieh, from The Dynamite Shaolin Heroes and Five Fingers of Death). If you remember Shaolin Martial Arts, you may recall that Pai Mei was said to have mastered not only the discipline of Steel Armor, rendering him effectively invulnerable to most forms of attack, but also a special technique of his own devising whereby he could circumvent Steel Armorís critical weakness by retracting his genitals behind the muscles of his body wall. Executioners from Shaolin goes even that one better, positing that Pai Mei can time the retraction to seize a foot or a fist aimed at his junk between those muscles as if catching them in a leg-hold trap! Zhi Shan is wholly unprepared for this triple-decker stack of super-powers, and he is handily defeated despite hitting the White-Browed Priest with the full arsenal of the Shaolin Tiger style. With the abbot slain, the remaining monks and lay disciples are unable to hold out against the combined forces of the Wu Tang clan and the Qing soldiery commanded by General Gao Jin-Zhon (Chang Tao, reprising his Men from the Monastery role).

Several of the lay disciples escape the massacre, however, none of them more worrisome to the templeís destroyers than Hung Hsi-Kwan (Chen Kuan-Tai, one last time). Gao leads the hunt for Hung personally, but his efforts are thwarted at the last moment by the heroic self-sacrifice of Tong Qian-Jin (Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, from Heroes of the East and Legendary Weapons of China). After slipping through Gaoís fingers for the second time, Hung and his followers adopt a cunning collective disguise to cover their continued activities in resistance to Manchu tyranny. They start posing as a traveling opera troupe (remember that Chinese opera is heavy on stage fighting, and encourages the acquisition of at least basic martial arts proficiency), roaming the coasts and rivers of southern China aboard a flotilla of junks called red boats. The Shaolin fugitives will visit a village, put on a subversive show (theyíre partial to operas of resistance to the 12th-century Mongol conquest, which have obvious parallels to the situation in their own era), kick a little Manchu ass as needed, and disappear onto the waterways before the authorities can figure out what just happened.

On one such stopover, Hung at last meets his matchó but not at all in the way that sounds. Immediately upon making landfall, his right-hand man, Xiao Hu (Cheng Kang-Yeh, from Challenge of the Masters and Ghost Ballroom), gets into a scuffle with a heckler by the name of Fang Yung-Chun (Lily Li Li-Li, of Shaolin Abbot and The Oily Maniac), who disparages the incognito rebelsí stage fighting as inauthentic showboat bullshit. The girl knows whereof she shit-talks, too, for she turns out to be sufficiently adept with the Shaolin Crane style to give Xiao a run for his money even after he switches from his stage kung fu to the real thing. Indeed, sheís good enough that Hung himself would need to get much rougher than he wants to in order to best her! Fang rethinks her position, though, once she realizes whom sheís trading blows with. The name of Hung Hsi-Kwan is well known in these parts, and Yung-Chun considers him a major inspiration. When the rebels set sail for the next village this time, she and her guardian uncle (Shum Lo, from The Cave of the Silken Web and Shaolin Temple) go with them. And in between their raiding and rabble-rousing, Hsi-Kwan and Yung-Chun find time to become first friends, then lovers, and ultimately husband and wife.

Eventually, though, General Gao catches on to the Shaolin fugitivesí ruse, and reacts with all the subtlety and restraint that one expects from an evil warlord. He orders all the itinerant opera boats in the province destroyed, and their crews arrested or killed as necessary. Thatís too much heat even for Hung Hsi-Kwan, so he and Yung-Chun vanish as deep into the Guangzhou hinterland as they can to raise their forthcoming child in peace. But although that means admitting defeat in the struggle against Qing oppression, Hung never forgets the more personal score he has to settle with Pai Mei on behalf of Abbot Zhi Shan. Hung hones his Tiger kung fu so singlemindedly over the next seven years that he not only leaves Yung-Chun more or less on her own to bring up little Wen-Ding (played at this stage by Dave Wong Kit, from Soul of the Sword and The Legend of the Flying Swordsman), but even entrusts her with the boyís education in the martial arts. Wen-Ding therefore learns his motherís Crane style rather than his fatherís Tiger, which is going to have implications later on. Regardless, seven years of preparation give Hung sufficient confidence in his abilities to challenge Pai Mei at lastó even if Yung-Chun is less than convinced of his readiness.

Let that be a lesson to you, gentlemen: when a wife as supportive as Fang Yung-Chun tells you youíre not yet ready to do something, youíre not fucking ready! Hung is wrong-footed just as easily as Zhi Shan by the White-Browed Priestís superhuman abilities, and although he escapes with his life from the Wu Tang Temple, that in itself is a measure of how inconsequential a threat Pai Mei deems him. Mind you, it isnít that the Wu Tang master doesnít try to kill his uninvited guest on his way out the dooró he just doesnít try as hard as he might. As Hung flees down the stone staircase leading up the hill to the temple, Pai Mei rolls an enormous boulder down after him, and only the unexpected intervention of Xiao Hu saves the defeated hero from getting squished. Xiao, having learned from Yung-Chun that her husband was off to challenge Pai Mei, had raced after him in the hope of imparting a secret he had learned which could have altered the course of the battle. The White-Browed Priestís invulnerability is imperfect after all, insofar as his acupressure points are susceptible to attack during the Hour of the Goató between 1:00 and 3:00 PM by the Western clock. Xiao sadly arrived too late to influence the course of todayís duel, and even more sadly, heís crushed himself when he tackles Hung out of the rolling boulderís path. But he nevertheless manages to pass along the secret of Pai Meiís weakness with his dying breath.

Hung trains for another ten years, this time with the aid of a bronze mannequin designed to teach pressure-point attacks even against an opponent capable (like Pai Mei inevitably is) of moving theirs around. What he refuses to do, however, is to allow Yung-Chun to diversify his repertoire by teaching him her Crane style. You see whatíll come of that, Iím sure. So does Yung-Chun, which is why she leans on her husband to swallow his manly pride and accept her instruction in the first place. Even Wen-Ding (grown by now into Wong Yu, of The Snake Prince and Dirty Ho) sees whatís what once his mother explains it to him. But some guys would rather be macho than alive, and Hung Hsi-Kwan, alas, is one of them. His rematch against Pai Mei is only slightly more successful for him than their original boutó just enough, in fact, to convince the White-Browed Priest that Hung cannot be allowed to survive this time. Thus it will fall to Wen-Ding, who fortunately isnít macho at all, to finish the job of avenging Zhi Shan, the Shaolin Temple, and his doomed, stubborn dad.

This business of Hung Hsi-Kwan dooming himself by refusing his wifeís instruction in Crane boxing is curious, because synthesizing the Tiger and Crane styles is precisely what heís supposed to have done to invent Hung Gar. That doesnít seem like a change that an informed storyteller would make unless they intended it to mean somethingó and Lau Kar-Leung was certainly informed on the subject of Hung Gar, since he practiced it himself. Iíve read nothing, however, to provide the slightest clue to what Lau was up to with this rather stark revisionism. Similarly, Iím not sure what to make of his portrayal of Hung Wen-Ding, or indeed whether Iím meant to see in it what I think Iím seeing at all. I said before that Wen-Ding isnít macho, but that might be a considerable understatement. Indeed, although I lack the grounding in Qing-era fashion necessary to be sure about this, it looks to me like the kid dresses and styles his hair like a little girl, even when heís supposed to be in his late teens. Now maybe thereís a tradition somewhere in the mix which has the Hungs raising their boy disguised as a girl in order to throw off enemies who might be less inclined to harm the daughter of a famous rebel leader than a son, but I couldnít find any trace of such a thing. Nor does Executioners from Shaolin explicitly state that or any other reason for the ladís seeming effeminacy, or indeed even acknowledge it except by implications that could equally well be meant to imply something else altogether. Again, itís all very mysterious to me. Maybe Lau is taking a subtle dig at Chang Cheh, who often seemed to equate heroism with a cartoonish sort of hyper-masculinity? Could Lau even be chiding Chang for inventing a Hung Hsi-Kwan who couldnít plausibly be imagined in his canonical role of merging the rather yinny Crane style with the extremely yangy Tiger? Or might the director instead have been weighing in on some controversy current among Chinese martial artists at the time? I donít know where Iíd even begin to look for evidence if itís the latter.

Mind you, it would never have occurred to me to wonder about any of that two years ago, before I got it into my head to add martial arts movies to my repertoire in a serious way. Nor do I believe even now that those unanswered questions had more than a marginal effect on my assessment of this movie as the unfortunate final sputter of the original Shaw Brothers Shaolin Temple cycle. More than anything, I think Executioners from Shaolinís generational approach to storytelling is just an inherently bad fit for action cinema, although I can imagine a couple tweaks that might have made for a slightly less clunky narrative. For instance, Pai Mei could kill Hung Hsi-Kwan in the first duel at the Wu Tang Temple, forcing an earlier handover to Hung Wen-Ding. Or better still, Hsi-Kwanís rematch with the White-Browed Priest could turn into a tag-team affair, with Wen-Ding disobediently following his father to the site of the battle, then entering the fray with exactly the fresh skill-set needed when it looks like Hung Senior is going down to a second and final defeat. Either way, Executioners from Shaolin has one retributive duel too many.

A major reason why the generational approach was a poor choice for this movie in particular is that Hung Wen-Ding doesnít get enough time at center stage to come into focus as a character, not least because his screen time is divided between two different actors of drastically different ages. Furthermore, most of the adolescent Wen-Dingís development concerns his growth as a martial artist, and while thatís certainly important in a kung fu movieó especially one that functions as a just-so story for the origin of a specific styleó we need to form a sense of the person, too. Meanwhile, I was surprised to discover how unappealing Chen Kuan-Taiís rendition of Hung Hsi-Kwan becomes without some more freewheeling, flamboyant character to act as a foil. General Gao (who badly needs a moustache to twirl) fulfills the latter function in the first act, while Fang Yung-Chun and Xiao Hu trade off with it in the second, but Hung has acts three and four all to himself for most practical purposes, and my God, what a pill he turns out to be on his own! Thatís another reason why Ni and Lau should have given Wen-Ding more attention before he takes over as Executioners from Shaolinís protagonist. Even if the kid never became a strong enough presence to stand on his own, Chenís dour, pig-headed stoicism would almost certainly have benefited from more close-quarters contrast against a swishy little mamaís boy who happens to have the answer to dadís most pressing kung fu problem.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact