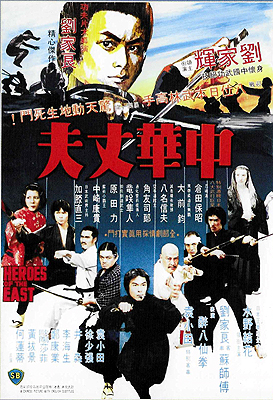

Heroes of the East / Shaolin Challenges Ninja / Drunk Shaolin Challenges Ninja / Challenge of the Ninja / Shaolin vs. Ninja / Zhong Hua Zhang Fu / Chung Wah Jeung Fu (1978/1979) **½

Heroes of the East / Shaolin Challenges Ninja / Drunk Shaolin Challenges Ninja / Challenge of the Ninja / Shaolin vs. Ninja / Zhong Hua Zhang Fu / Chung Wah Jeung Fu (1978/1979) **½

We’ve talked before about how difficult it is to translate comedy from one culture to another— about how benign violation doesn’t work if you don’t understand the norms being transgressed, unless perhaps they’re so universal to the human condition that cultural context is irrelevant. You’d therefore expect comedy of manners to be almost inherently incomprehensible across cultures, since manners are just about the most culturally dependent systems that humans have ever invented. Well, despite its generic fu-film title, Lau Kar-Leung’s Heroes of the East is a comedy of manners— and what’s more, it hinges upon a clash of Chinese manners against Japanese, so the average Western viewer will be doubly in the dark. Nevertheless, not only did I find this movie funny, but I’m pretty sure I found it funny on approximately the level that Lau and screenwriter Ni Kuang intended. It might have helped a bit, however, that I’m familiar with The Taming of the Shrew, which Heroes of the East rather strongly resembles if we posit that the main bone of contention between Petruchio and Catarina is that they have no respect for the martial arts traditions of each other’s homelands.

When Ho To (Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, of Breakout from Oppression and Dirty Ho) was a child, his father (Ching Miao, from Pituitary Hunter and Disciples of the 36th Chamber) made a contract for him to marry the daughter of a prominent Japanese businessman. (Heroes of the East appears to be set either late in the 1920’s, or very early in the 1930’s, during the brief interval of relative tranquility between the end of the Warlord Era and the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.) Now that the time has come to fulfill that contract, Ho can think only of how he might escape from it. He’s sure that his fiancée, Yumiko— or Kung-Zi in the Chinese reading of her name— will have grown up to be as ugly as a horse, and what could he possibly have in common with a Japanese woman anyway? When Dad comes home bringing Yumiko and an entourage of her relatives, he finds To trying to play sick with the help of Shou Kwan (Cheng Kang-Yeh, of The Boxer from Shantung and The Lizard), the dimmest but most loyal of the household servants. The picture changes once the reluctant groom sees Yumiko for himself, however. Turns out she’s grown up to be Yuka Mizuno, who doesn’t look one little bit like a horse. All of To’s impassioned arguments about self-determination and the obligation of every man to find his own way in life disperse like a puff of smoke as soon as he realizes that his father has arranged for him to marry a pretty girl.

But despite Ho’s conspicuous change of heart, the newlyweds are together less than a week before rumors begin circulating to the effect that he habitually beats Yumiko. Even To’s father voices to him in veiled terms his disapproval of men who slap their women around! Mind you, no one’s ever seen any such thing transpire between the couple, nor does the new Mrs. Ho ever show any sign of welts or bruises. But not a morning goes by when somebody doesn’t hear Yumiko crying out from inside the walled garden behind the villa. To is pretty sure that Shou is behind the spreading tales of marital malfeasance, but when confronted, the servant pleads that he spoke only the truth. In fact, if Young Master Ho will accompany Shou to the garden right now, he’ll hear for himself how brutally… Waitaminute… That can’t be right, can it? No, I guess not. Actually, the daily ruckus in the garden is caused by Yumiko practicing her martial arts! It never occurred to her that her husband might be into kung fu, and she therefore never bothered to look for his training gym adjacent to the other courtyard.

Now you might expect that the two spouses would be brought closer together by the unexpected discovery of their mutual devotion to the ancient arts of buttkickery— and if To and Yumiko had been brought up in the same country, they probably would be. But Yumiko practices Japanese fighting arts, and To finds that totally unacceptable. Karate is unladylike in its aggression. Judo causes Yumiko’s gi to gape immodestly down the center of her chest. And ninjutsu is just unseemly all around— all that sneaking and misdirection and concealed weaponry! Don’t get To started, either, on the crate full of armaments that Yumiko has delivered from home and orders the servants to install in the gym, displacing his own arsenal of proper Chinese jians, daos, and butterfly swords. The couple fall to strident squabbling, exaggerated displays of reciprocal jingoism, and ultimately hand-to-hand combat. To usually comes out on top in the latter contests, enraging Yumiko even further. (He does seem to have a hard time countering ninjutsu, though, which I’m sure won’t turn into an important plot point later…) Eventually, she gets fed up, and moves back home to Kyoto while To is out of the house, awkwardly explaining to his sifu (Simon Yuen Siu-Tin, from The Mystery of Chess Boxing and The Dragon Lives Again) and his fellow students why he keeps showing up for class with mysterious minor injuries.

Not to worry, though— Shou Kwan has a can’t-miss plan for getting his mistress back! All Ho has to do, he says, is to send her the most arrogantly worded letter of challenge that he can devise. Honor will demand that she return at once to duel him, and they can kiss and make up once the battle is over, and the superiority of one spouse’s martial traditions over the other’s is decisively demonstrated. The fact that To agrees to this scheme suggests that maybe Shou isn’t the dim one here after all. When Yumiko gets To’s letter, she’s hanging out with Takeno (Yasuaki Kurata, of A Girl Called Tigress and The Seventh Curse), her dear old friend, never-quite-lover, and ninjutsu sensei. Takeno naturally wants to know what the missive said to upset her so, and he gets pretty fucking upset, too, after she hands it over for him to read for himself. Takeno takes the letter to his sensei, Grandmaster Kato (Naozo Kato), who agrees that the terms of Ho’s challenge to his wife are an affront to all practitioners of Japanese martial arts everywhere. As such, not only will Kato and Takeno escort Yumiko back to China to answer the insult, but they’ll also bring along a karate master (Tetsu Sumi), a judo master (Hitoshi Omae, from Five Tough Guys), a kendo master (Riki Harada), and one expert each in the use of the spear (Nobuo Yana), sai (Yasutaka Nakazaki), and nunchaku (Manabu Shirai). Ho To will have to fight all of Kato’s champions before the grandmaster considers the matter resolved. In other words, Heroes of the East is about to transform itself from a kung fu Taming of the Shrew into Shaw Brothers’ precognitive Scott Pilgrim vs. the World!

I had to laugh when I realized what the title Heroes of the East was supposed to mean: not “East” as in the Orient, but “East” as in Japan specifically, which after all is east of China— and the “heroes,” meanwhile, are the martial artists that Kato rounds up to defend Japanese honor! It’s a small but telling example of what a peculiar movie this is. Heroes of the East builds its conflict around frictions between Chinese and Japanese culture, but takes as its setting the one historical moment of the past 130 years when those frictions wouldn’t have been proxies for deadly serious historical or geopolitical issues. It’s theoretically about two people in love learning not to be jerks to each other over national pride, but it never actually resolves that plot. Instead, it pivots to a thematically related but conceptually distinct one in which Ho learns to respect all martial artists, regardless of the national origin of their school or style. And as is frequently the case in 1970’s kung fu movies, Heroes of the East comes to a halt before it can really be said to have come to an end.

The shift from To vs. Yumiko to To vs. the Heroes of the East accompanies a shift from kung fu comedy to a somewhat more serious breed of action. To be sure, Heroes of the East is unusually light-hearted, even in the fight scenes. Several of the Japanese champions are conspicuously odd-looking and eccentric. One of them gets defeated by an improvised gag tactic when Ho is unable to make any impression on him by more orthodox means. And Takeno climaxes the final fight by resorting to an imaginary and patently absurd fighting style called Crab Fist. (Ho counters with the Shaolin Crane style; cranes, after all, eat crabs.) And on top of that, I’m pretty sure this is one of only two martial arts movies I’ve ever seen in which nobody whatsoever gets killed. Still, only the fights between To and Yumiko are really supposed to be funny on the whole. The tonal switch is unfortunate, not only because Lau was doing so well at the comedy-of-manners stuff, but also because his approach to the battles against Kato’s men flies in the face of the movie’s main themes. For To to learn his lessons convincingly about giving both his wife and her nation’s fighting arts their due respect, he really needs to lose at least a couple of the fights leading up to the showdown against Takeno— or at the very least, he needs to win more of them by not-quite-kosher ploys of the sort that finally brings down Hitoshi Omae’s judoka. And ideally, he shouldn’t be able to beat Takeno without synthesizing his own Chinese practices with techniques copied from Yumiko. However, Lau too has national pride on the line here, and his need to assert the innate superiority of Southern Chinese kung fu wins out in the end to the film’s detriment.

Fortunately, Heroes of the East is better as a comedy than it is as a martial arts movie. To begin with, there’s the sheer, cracked inventiveness of making kung fu vs. ninjutsu the lynchpin of a “two newlyweds discover that there’s something they can’t stand about each other” plot. Then as a bonus feature to that, Lau makes great comic use of the Hong Kong trope which has it that Chinese martial arts are more elegant, while their Japanese counterparts have more raw destructive power. Not only is Yumiko’s karate practice unladylike, but it absolutely wrecks the garden, too. Lau makes amusing use of other points of cultural disjunction, as well— my favorite being the scene in which Yumiko refuses to eat sitting down at a high table anymore, insisting that kneeling on cushions before a portable raised tray is the only suitable method for civilized people, and ultimately getting into a totally uncivilized food fight with her husband over the matter. And as the latter ought to imply, Heroes of the East is well stocked with intricate slapstick on the Jackie Chan model, including a sequence in which Lau himself appears as the inebriated hobo from whom Ho learns drunken boxing by sending his retainers one after another to annoy the bum into employing his moves on them. It’s enough to overcome the movie’s weaknesses as an action picture, even if Heroes of the East is less successful at integrating comedy and mayhem than some of the more famous Hong Kong films in that mode.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact