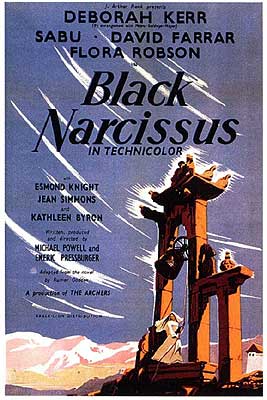

Black Narcissus (1947) ****

Black Narcissus (1947) ****

Nunsploitation as we know it pretty clearly begins with The Devils, but the genre didn’t spring fully formed from Ken Russell’s brow. A hidden history of antecedents preceded The Devils into release by decades— hidden all the better because nunsploitation in its mature form is itself is so little discussed. Furthermore, one of the key specimens for the prehistory of the genre is a film that few modern viewers would ever think to seek within the pedigree of such disreputable pictures as Flavia the Heretic and The Sinful Nuns of St. Valentine. In 1947, though, when Black Narcissus first appeared on theater screens, audiences would have had no trouble imagining it as a harbinger of scummier Naughty Nun movies to come. Indeed, Black Narcissus was reckoned scummy enough itself in its day to warrant a “condemned” rating from the Catholic Legion of Decency! Had Catholicism been as prevalent in Britain as it was in the United States, Black Narcissus might even have had the same nuclear impact on the career of co-writer/co-director Michael Powell as Peeping Tom did thirteen years later. Luckily for Powell, however, the Church of England proved less neurotically protective of its nuns’ good names, and he and his partner, Emeric Pressberger, weathered the controversy with their reputations mostly intact.

It may surprise some of you to learn that there’s an Archbishop of Calcutta. It certainly surprised me. I suppose somebody has to save the souls of the Heathen Hindoos, though, and with so bloody many of them in His Majesty’s domains, it probably would take an operation of archiepiscopal scale to have any chance of catching them all. Now nobody converts heathens like nuns, so it stands to reason that the archbishop would want to seed the countryside with as many convents as possible. Somewhere up in the Himalayas, a rajput general (Esmond Knight, from The Gaunt Stranger and Peeping Tom) knows just the spot to put one. Atop one of his mountains is the palace where his forefathers used to stockpile their women. So when you think about it, the place was practically a nunnery to begin with— except of course for all the screwing. The archbishop agrees that the facilities are uniquely suitable (unfortunate past employment notwithstanding), and soon the abbess of a convent in Calcutta (Nancy Roberts) finds herself mulling over which of her subordinates she can afford to part with to set up a satellite operation. Mother Dorothea selects Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr, from Eye of the Devil and The Innocents) to run the new Convent of St. Faith, and assigns to her a skeleton staff of four. Obviously it’ll be rough going at first with so few nuns to go round, but the archbishop already made one unsuccessful attempt to turn the general’s disused orgy house into a monastery for men, and Dorothea is presumably under instruction not to over-commit to the new venture.

Three of Sister Clodagh’s underlings seem reasonably chosen. Sister Philippa (Flora Robson, from Fragment of Fear and The Shuttered Room), the oldest of the bunch, is a hard worker and a fount of horticultural knowledge. The sisters will be responsible for growing their own food in the long run, so Philippa’s skill in the garden will be indispensible. Sister Briony (Judith Furse, of Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire) is as strong as an ox and twice as unimaginative— both obvious assets in an undertaking that calls for lots of uncomplaining labor. And Sister Blanche (Village of the Damned’s Jenny Laird) is so pleasantly dispositioned that the other nuns all call her “Sister Honey.” If anyone can charm the natives into abandoning their ancestral gods, it’s her. The only one I’m not so sure about is Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron, from Twins of Evil and Craze). Truth be told, Dorothea and Clodagh aren’t so sure about her, either. Sister Ruth has been something of a loose cannon ever since she took her vows. Moody, flighty, hyopchondriacal, quick to rile and slow to forgive, Sister Ruth is exactly the sort of person I wouldn’t want to be stuck with at close quarters in a hostile environment. But Mother Dorothea hopes that the extra responsibility will be good for her, that Ruth will be driven to become more dependable by the mere fact that Clodagh and the others have no choice but to depend on her. And once Dorothea has made up her mind, Clodagh is in no position to refuse her.

The nuns’ arrival at the palace is an occasion for 360-degree culture shock. Not only do the locals not speak English, but they don’t even speak any Indian language familiar from Calcutta. Angu Ayah the caretaker (The Human Monster’s May Hallatt) offers the sisters no respect whatsoever, not even bothering to learn their names. (Bewilderingly, she refers to all the nuns interchangeably as “Lemony.” If anyone has a clue what that’s about, I’d love to hear from you.) Joseph Anthony (Eddie Whaley Jr.), the interpreter hired for the convent by the general, turns out to be a little boy of indeterminate age. (Joseph claims to remember six birthdays, but figures he might have had as many as four before he was old enough for them to stick with him.) Mr. Dean (David Farrar), an Englishman apparently in the general’s employ, has gone native to a degree that the sisters find scandalous— but not half as scandalous as his habit of hanging idly around the convent where no man is supposed to be, waiting for the embarrassingly inevitable moment when this or that nun needs his help with something. The general’s teenaged son (Sabu, from Cobra Woman and The Thief of Bagdad) shows up, expecting to be educated in a panoply of collegiate subjects, even though Clodagh’s been advertising St. Faith’s teaching apparatus as strictly a primary school for girls. And speaking of girls, Mr. Dean dumps one of those on the sisters, too— a troublesome, amorous teenager by the name of Kanchi (Jean Simmons, of Footsteps in the Fog and Dominique Is Dead), who might, just maybe, be his own bastard daughter. St. Faith even has religious competition, insofar as a native holyman— the general’s uncle, no less!— has been sitting in silent and immobile contemplation on the property for as long as anyone can remember, and is not about to be moved for the sake of a bunch of spiritual lightweights like Clodagh and her sisters.

None of that stuff causes half as much trouble for the nuns, though, as the environment of the palace itself. Foreign as it must have seemed to Clodagh and the others when they arrived, Calcutta was both a cosmopolitan city and a long-established administrative center of the British Empire. It was functionally an outpost of the West, and it had been configured over the centuries to support a semblance of the Western lifestyle. St. Faith isn’t like that, however. The local village has no British military or consular presence, nor any of the social or cultural infrastructure that might be expected to spring up to serve the needs of such people. The natives there treat the nuns not as formidable representatives of a superior, conquering civilization, but as a bunch of foreign weirdos renting out their rajput’s harem. Indeed, the only reason the convent’s school and clinic have any customers at all is because the general pays all his subjects to avail themselves of the nuns’ services. Even the air is strange to Clodagh and her subordinates— thin, crisp, and totally devoid of the comforting coal smoke of home. Calcutta at least had the decency to stink like a proper city! In this place, where their vows, their rules, their whole way of life are afforded no deference, the sisters find themselves compulsively pondering the choices that led them here, and even more worrisome, the alternatives that might have led them elsewhere instead. Sister Clodagh can’t stop thinking about the man who jilted her when she was little more than an adolescent, and while she doesn’t exactly regret devoting herself to the service of Christ in the aftermath, she’s tormented of late by specters of the life she might have had as a wife and mother. Sister Philippa is tight-lipped about the personal history that has risen up to haunt her, but she finds herself rebelling against her present circumstances by planting extravagant beds of flowers all around the palace in plots that were supposed to support sensible crops of lettuce, beans, and potatoes. And Sister Ruth, roiling cauldron of passions that she is, falls madly in unrequited love with Mr. Dean. The latter development is even more ominous than it sounds, too, because Dean has maybe just a bit of a thing for the sister superior.

As it happens, the crisis point comes via a sad but seemingly unremarkable incident in the course of the nuns’ regular duties. One of the native women comes to the dispensary bearing a deathly ill infant. Sister Blanche sees at once that the child hasn’t a chance given the primitive treatments available at the convent, and sends the mother away with no more than an admonition to let the child have as much rest and quiet as possible. Sister Ruth, however, feels strongly that the nuns must try to do something, so she slips the woman a vial of castor oil as a palliative. When the baby inevitably dies, the villagers blame the nuns’ black magic, and overnight, all the natives save little Joseph Anthony begin shunning the outsiders. With no more children to teach, no more patients to heal, and no more would-be converts to preach to, the sisters of St. Faith are left alone with their increasingly tortured thoughts. No one’s thoughts are more tortured than Sister Ruth’s, which circle obsessively around the villagers’ verdict that she poisoned the sick baby. The ensuing crises of conscience, faith, and vocational conviction prove too much for her, and she renounces her membership in the order. But it’s only after she discards her habit to pursue her feelings for Dean that matters spin completely out of control.

Black Narcissus makes a sharp zigzag after Sister Ruth loses it. When Sister Clodagh walks in on her packing her bags, dressed in street clothes and with a makeup kit at the ready, the movie reinvents itself without warning as something like a festively colored, tropical film noir, with Ruth (no longer Sister Ruth) as its twitchy, unpredictable femme fatale. And once Ruth discovers that Dean does not return her affections, Black Narcissus undergoes a more startling transformation yet, foreshadowing the gialli of the 60’s and 70’s, complete with a suspenseful stalking and Bava-esque lighting schemes. The Italian horror connection is strengthened, too, by the means Powell and Pressberger used to create St. Faith and its environs. The convent was purely a figment of Pinewood Studios, its breathtaking exteriors nothing but a confection of miniatures and matte paintings. That sort of reliance on models and glass mattes would later be a Mario Bava signature, of course, and esthetically speaking, the movie that this one’s climax reminds me of most is Kill, Baby… Kill! Mind you, it’s possible— maybe even easy— to make too much of the similarity, and to give thereby a false impression of Black Narcissus. The final-act genre jumps are so strange and unexpected, though, that I simply must try to make something of them.

We’re on much firmer ground linking Black Narcissus to The Devils and its spawn, however. Powell and Pressberger obviously couldn’t be as graphic as Russell could 20-odd years later, but Black Narcissus is remarkably explicit just the same about the sexual nature of the longings that undo the Convent of St. Faith. And naturally it’s no accident that these nuns (Sister Philippa excepted) are all far younger and better-looking than the ones who would tell this movie’s contemporary American viewers that they were going to Hell for watching it. But unlike most full-blown nunsploitation pictures, Black Narcissus is fairly serious about engaging with the issues behind the titillating spectacle of nuns in the dual throes of lust and regret for paths not taken. When Powell and Pressberger show the sisters of St. Faith acting up and getting into trouble, it’s because the filmmakers are genuinely interested in the strain it places on a person to go through life with whole domains of experience arbitrarily walled off. And it’s also because they’re skeptical about whether all the sacrifice and self-denial even accomplish what they’re supposed to in the first place. After all, can the discipline of the convent really have changed Clodagh and her sisters very much if it takes so little to knock them off their chosen path? Black Narcissus also reveals a strong skepticism about the claims of institutional Christianity in general. Clodagh and the others approach religion as a long list of things they’re not supposed to do: don’t drink alcohol, don’t give in to sexual desire, don’t place yourself in proximity to temptation, etc. The idea that Christ and his teachings might set a positive example for what they are supposed to do doesn’t seem to enter into their thinking. While the nuns focus on how to keep the villagers from breaking their rules, it’s the loutish Mr. Dean who continually nudges them to consider what the general’s tenants actually need. Dean is the only Westerner who lives among the natives, who accommodates himself to the rhythms of their lives, who makes the effort to understand and to appreciate their culture. Contrast that to Sister Briony, who is visibly annoyed upon arriving in the mountains that these savages insist on speaking their own language, or to Sister Philippa, who blithely lumps together Africans, Indians, Malays, and who knows what other non-European peoples under the heading of “black.” The complete picture is one of the convent, the church, and indeed the British Empire all serving the same ignorant, arrogant impulse to control things that would be better taken on their own terms, even if the latter involves a bit of discomfort up front or a steep learning curve. And when you put it like that, Black Narcissus looks twice as subversive in the context of 1940’s Britain as any of its spiritual grandchildren looked in the context of 1970’s France or Italy.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact