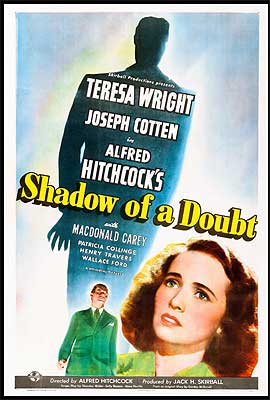

Shadow of a Doubt (1943) ****

Shadow of a Doubt (1943) ****

In 1943, there wasn’t any such thing yet as film noir. To be sure, the first generation of movies that would one day be called that were already being made, but it wasn’t until French critics got hold of them, after the end of World War II reopened normal transatlantic commerce, that they were reinterpreted as a single, coherent phenomenon in need of a name. Still less was there any such thing as a Portrait of a Psychopath movie on the model of Deranged or Don’t Go in the House. It’s startling, then, to watch Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, and to recognize in it aspects of both types of film, even though it can’t possibly have been intended as either one. It’s even more startling, though, to recognize so many signs that so dark, bleak, and nasty a movie could owe its existence at least partly to the folks at Universal wanting a Rebecca of their own.

He’s apparently been calling himself “Spencer” lately, but the man we meet dozing in a darkened upstairs room in some Philadelphia flophouse is really Charles Oakley (Joseph Cotton, from The Man with a Cloak and The Screaming Woman). Oakley presents an incongruous appearance, with his sharp suit, shabby lodgings, and great pile of cash scattered haphazardly across the nightstand. Before we’ve had much chance to process that, however, Oakley’s landlady (Constance Purdy, who played a comparably minor role in Flesh and Fantasy) bustles in and begins maternally tidying up, explaining as she does so that she just turned away some callers for him, as per his instructions. She says they identified themselves as friends of his, but mentioned neither their names nor the object of their visit. If Charles would like to see for himself, they’re still hanging out on the corner across the street. Oakley does indeed have a look after the landlady has gone about her business, and sees two nondescript fellows clad in the standard 1940’s male uniform of shapeless and somewhat ill-fitting gray suits (Carey MacDonald, from Summer of Fear and These Are the Damned, and Wallace Ford, of Murder by Invitation and The Ape Man), loitering with that species of purposeful nonchalance that nobody ever adopts unless they’re laying an ambush. Not wishing to be waylaid, Oakley gathers his money and sets off to lose his two pursuers in the warren of alleys that constitutes his neighborhood. Then, once he’s satisfied himself that he’s beyond the reach of prying eyes and ears, he sends a telegram to his sister, Emma (Patricia Collinge), announcing that he’ll be coming to stay for a while with her and her family. And just to make absolutely certain that he won’t be caught out again by the men in the gray suits, he books his train under yet a third name, posing as an invalid too sick to hobnob with his fellow passengers.

Emma Oakley, strictly speaking, is Emma Newton these days. She lives in Santa Rosa, California, with her husband, Joseph (Henry Travers, from the 1935 version of Seven Keys to Baldpate and The Invisible Man), and three children ranging in age from the upper single digits to the threshold of adulthood. Joseph is a cashier at the local bank, which suffices in an economic backwater like this one to support a modest middle-class lifestyle, but the size and solidity of the Newtons’ house seems to imply that the family was once considerably better off. Maybe Joseph used to own a business that got wiped out by the Depression. In any event, Emma and her son, Roger (Charles Bates, from Son of Dracula and The Curse of the Cat People), are the “normal” ones in this household. She’s everything you expect from an aging, small-town housewife of the early 1940’s, while he’s the kind of mildly mischievous, manageably rambunctious tyke that you’ve seen a hundred times in films of this era. Joseph and the girls are more eccentric.

The Newton patriarch’s great passion is crime literature, the more lurid the better. He subscribes to as many of the detective fiction and true crime pulps as his tight budget will allow, and trades them back and forth with his even bigger crime-nerd pal, Herbie Hawkins (Hume Cronyn, later— much later— of *Batteries Not Included and Cocoon). Joseph and Herbie also have a running gag going in which they can’t spend more than ten minutes together without the conversation turning to how they’d go about murdering each other. Middle child Ann (Edna Mae Wonacott) is a precociously self-serious bookworm, and considers her father’s hobby to be both embarrassingly juvenile and in appallingly poor taste. She’s like the co-protagonist of a cheesy body-swap comedy in which a prim junior high school principal trades places with one of her students. But the real misfit among the Newtons is Charlotte, the firstborn (Teresa Wright, of The Search for Bridey Murphy and Crawlspace). Far more than either of her parents or siblings, Charlotte— but call her Charlie— is conscious of the limited horizons confronting her. She chafes against the family’s straitened material circumstances; against the lack of culture, excitement, and opportunity in Santa Rosa; and most of all against the complacency of her family and friends, all of whom seem basically content with an existence in which each day fades imperceptibly into the next one, forever. Charlie wants to live, even if she doesn’t entirely understand what she means by that, and the one person she’s ever met who seemed to be on the same wavelength was the uncle for whom she was named. When we meet the Newtons, this Charlie is in a absolute tizzy over the rut in which she feels the family to be stuck, and she begs her mother to let her invite the other Charlie over for an extended visit. Emma agrees, and the girl is in the process of composing a telegram to her uncle proposing a trip to California when Oakley’s telegram arrives, announcing that he’s already on his way.

The first thing about Uncle Charles that becomes apparent upon his arrival in Santa Rosa is that he’s not merely well-heeled and careless of his money, but filthy rich and exceedingly generous. His gifts to the Newtons in return for their open-ended hospitality include an elegant watch for Joseph, a fur stole for Emma, and an emerald ring (not a little emerald, either) for Charlie. The 40 grand that Oakley deposits in Joseph’s bank the following morning sounds like an awful lot of money even now, but in 1941 (Shadow of a Doubt takes place two years in its own era’s past, seemingly to avoid the complications of having to acknowledge the war), it was equivalent to well over 800,000 of today’s diminished dollars! And the speed with which Charles makes a name for himself among the local charitable and civic groups is a sight to behold. He’s going to become a popular man around here by the time he moves on to wherever his lifelong wanderlust takes him next.

It doesn’t take a very sensitive nose, however, to discern that Oakley’s money smells fishy. For one thing, although Emma is fond of saying that her brother is “in business,” she clearly has no idea what that business might be— and Charles himself never volunteers the information, even when it would be natural to do so. Also, there’s every indication that Oakley has been just carrying most of his vast fortune around, whether on his person or in his luggage. Granted, Black Tuesday was still recent enough history in those days that a lot of people had little trust in banks, but that’s an insane amount of cash to keep stuffed into your suitcase and coat pockets. Then there’s a whole host of miscellaneous suspicious details. Joseph doesn’t notice this, having always favored pocket watches, but that wristwatch his brother-in-law gave him is a lady’s model. The ring that Charlie gave Charlie is inscribed inside the band with some other couple’s initials— and the girl does notice that. Her uncle’s reply that the jeweler must have suckered him by selling him a used ring in place of the new one he thought he was buying is plausible enough on its face, but considerably less so when you consider what a sharp customer Oakley seems to be in every context that doesn’t involve buying presents for his relatives. Shadiest of all, Charles has allowed himself to be photographed only once in his life, when he was perhaps ten years old, and he’s positively militant about keeping it that way.

It’s an open question, then, which side looks less trustworthy when those two guys from the opposite coast arrive in Santa Rosa, claiming to be survey-takers studying lifestyles and public opinion in average American communities. Oakley is appalled at the guilelessness with which Emma agrees to admit the strangers into her home in order to photograph it and to interview all the members of the family. He flatly refuses to have anything to do with the whole affair, and Charlie backs him up with the full fire of adolescent dudgeon despite plainly not understanding what her uncle finds so objectionable about the situation. Even so, it’s a bizarre performance indeed that Charles puts on when Jack Graham and Fred Saunders— assuming those really are their names— return to the Newton house to make good on their pact with Emma. He sneaks out down the back stairs like a comic-opera adulterer, and when Saunders manages to snap a picture of him anyway, he angrily demands that the photographer hand over the film cartridge, in terms which unmistakably warn that he’s prepared to resort to violence if he doesn’t get his way. Even Charlotte is taken aback, although she still sides with him against the intruders. Just the same, she isn’t so dead set on repelling them that she won’t succumb to flattery when Graham asks Emma’s permission to have the girl show him around Santa Rosa that evening.

The ensuing not-quite-a-date seems to be going well for both participants when Charlie suddenly has an epiphany: Graham and Saunders are detectives! Everything they’ve said since showing up on the doorstep the other day has been complete and total bullshit, and even this night out with Jack has been nothing more than a bid to pump her for information of some kind! Furious though she is over how she allowed herself to be played, Charlie nevertheless hears Jack out about his mission in Santa Rosa, but gets a lot more than she bargained for. Charles Oakley, it turns out, is one of two suspects in a case known to the press as the Merry Widow Murders. He (or perhaps another man back in Boston) is in the habit of romancing rich widows to exploit their generosity, strangling them as soon as he’s had enough of them, and then helping himself to whatever they have in the way of cash money and salable goods before moving on to new hunting grounds. Charlie refuses to believe any such thing about her beloved uncle, and insists that Graham take her home at once.

As soon as she’s alone, though, Charlotte gets to thinking. She thinks about her uncle’s aversion to having his picture taken, which would certainly facilitate the lifestyle of nomadic homicide that Graham attributes to the Merry Widow Killer. She thinks about how strong Uncle Charlie’s hands are— more than strong enough to crush the life out of a dozen or so unsuspecting middle-aged ladies. She thinks about the wads and wads of bills in his pockets, untraceable to any specific economic activity. Most of all, she thinks about a strange incident from the other night, when she caught Charles going to seemingly inordinate lengths to prevent anyone else from reading a certain item in the evening paper. Charlie races to the public library, arriving exactly at closing time, but finagles three minutes in which to browse the newspaper racks. Sure enough, the story that Oakley tried so hard to conceal describes the escalating hunt for the Merry Widow Killer, recounting his crimes in sufficient detail to leave Charlie literally nauseous. That isn’t the worst part, though. No, the worst part is the name of the most recent victim, whose initials are a perfect match for the inscribed dedication inside the band of that ring her uncle gave her. And before Charlie has a chance to sort through more than the most immediate implications of what she’s now pretty certain she knows, she learns something even more chilling. Uncle Charlie has decided to settle down at last, right there in Santa Rosa.

The last thing I expected going into Shadow of a Doubt was that I would come out of it with a proper-ass favorite Alfred Hitchcock movie. My longtime readers know that Hitchcock is a director who consistently rubs me the wrong way, even as I recognize the extraordinary magnitude of his talent and ability. I’ve always thought of him as sort of an Yngwie Malmsteen of filmmaking, ever eager to show off his chops irrespective of whether the work as a whole benefits from any given display of virtuosity. But Shadow of a Doubt showed me an Alfred Hitchcock I’d never seen before, exhibiting a kind and degree of artistic self-discipline that I wouldn’t have believed he had in him. The clearest lens through which to see it is to compare the final shot of the library scene here to the one in The Birds that follows Lydia Brenner’s discovery of the first fatality in Bodega Bay. In the latter, as Lydia climbs into her pickup truck and races home on the verge of hysteria, we’re shown the drive in a series of distant long shots echoing Melanie Daniels’s arrival in the village, the vehicle resembling a tiny toy as its wheels toss up lingering puffs of road dust to mark its passage. It’s a lovely image, and so attention-getting that it’s been lodged in my head for 23 years, but it doesn’t mean anything. Worse still, it disrupts the mood of the scene, thrusting us forcibly back into “coastal pastoral” mode at the exact moment when the film is finally getting down to business. In contrast, Shadow of a Doubt’s most try-hard, look-at-me image fully warrants its show-stopping, because it’s the thesis statement for the entire picture. As Charlie folds up the newspaper decisively incriminating her uncle, the camera shifts positions to the mezzanine overlooking the main reading room, pulling steadily back from her as she trudges out of the darkened, empty library, so that she looks smaller, more helpless, and more isolated with every step. You can feel the weight of Charlie’s unwelcome new knowledge descending on her, its very nature precluding her from attempting to share the burden with anyone. After all, she’s loved Charles all her life— how can she bear to expose him, knowing that to do so is to condemn him to the electric chair? And think what it would do to her mother! But how can she live with herself, either, if she doesn’t turn him in? Worst of all, the only person she knows with the worldly wisdom to help her cope with such a dilemma is Uncle Charlie himself! So not only does this shot tell you things, but it tells them more eloquently and more elegantly than a less obtrusive presentation of the same action could ever hope to, while simultaneously dispensing with the need for entire pages’ worth of dialogue that would probably have come out clunky and unnatural-sounding anyway. This is how you do it— and more importantly, it’s also why you do it.

That kind of careful attention to detail and conscious exploitation of cinema’s unique strengths as an art form is all over Shadow of a Doubt, too. Indeed, this is one of those rare films in which the imagery, performances, and narrative reinforce one another so adroitly that it becomes nearly impossible to tease apart the elements’ individual contributions. Take Joseph Newton and Hubie Hawkins as a representative example. On one level, those guys are the comic relief, and Henry Travers and Hume Cronyn play them accordingly. But due to the specific nature of the humorous fixation they share, they also function as a sort of upside-down Greek chorus. They should have unique insight into the workings of character driving all the action, but in fact they’re totally oblivious to every bit of it. Hawkins, indeed, is so unobservant that he fails to grasp what’s going on even in the midst of saving Charlotte from a deathtrap laid for her by Uncle Charles! And if you look closely, you’ll see that Hitchcock prefers to film the crime nerds in such a way that whenever they’re together, they crowd everything else out of the frame, creating a subtle but potent visual metaphor for their ironic obtuseness.

The fact that Charlie receives so little help from the people who should, in theory, be best positioned to spot the danger facing her is part of what makes Shadow of a Doubt feel noirish, even though its subject matter falls a bit outside the typical bounds of early film noir. The recurring noir theme of the system’s unreliability looms large here, too, for not only do developments in Boston eventually convince the detectives that they’ve been chasing the wrong man, but Uncle Charlie’s protective coloration, so to speak, proves so perfect in the end that his funeral following the final showdown sees him eulogized as a hero to his adopted hometown who was taken from the community much too soon. Only Charlotte knows the truth, and the only person with whom she could even consider sharing it is Jack Graham. It’s enough to make you wonder whether Charles might have emerged altogether victorious had the Hays Code not demanded his punishment.

Naturally, though, it’s the proto-Portrait of a Psychopath stuff that really gets my attention. What makes Uncle Charlie such a compelling villain in that mode is that his motivations aren’t readily calculable from factors like greed or bloodlust. And because we never actually see him kill, we’re unable to test any hypothesis we might reach about what drives his most depraved behavior. We know he doesn’t care about wealth per se, although he certainly enjoys the benefits of having it. His preference for post-menopausal widows suggests that murder for him is not a sex thing in any ordinary sense, either. The anecdote that Emma relates about a brain injury he suffered in childhood might be taken as an origin story for his homicidal tendencies, but tells us nothing about how he subjectively experiences the act of killing. The most informative hints come out in conversation between the two Charlies during the phase of the film in which she knows what he’s done and he knows that she knows, but neither one of them has quite decided yet where that leaves them. Some of what Charles says seems to imply that he kills in part because he recognizes his own monstrousness, and wrongly assumes that it’s a universal aspect of the human condition. I mean, if everyone really were a conscienceless, cold-blooded predator, then who’d be to say that Oakley wasn’t performing a public service by taking out a couple dozen of us, right? And yet the affection that Charles displays toward his sister and niece seems absolutely genuine, and I fully believe that he regrets it when he decides that Charlotte will have to die. Joseph Cotten is terrific in the part, too. Although he was generally cast in heroic and/or romantic leading-man roles during this phase of his career, Cotten has always struck me as somehow shady, so that I can never be entirely comfortable with him as a good guy. That’s exactly the vibe Uncle Charlie needs; he has to be someone whom everyone around can plausibly accept without question as a standup chap, even though he gives you the heebie-jeebies.

Or, to put it another way, Uncle Charlie should come across as a 20th-century update of the Gothic antihero— someone who sweeps the virginal young heroine off her feet, but has a whole Sedlec Ossuary’s worth of skeletons rattling around in his closet. That, more than anything, is what leads me to suspect that Universal were hoping for a bit of reflected Rebecca glory from this, their second Alfred Hitchcock picture. And indeed a number of recognizable Gothic themes are present in Shadow of a Doubt, even if they mostly appear in mutated or disguised form. Oakley may not be the heir to a family curse and a haunted castle, but he surely is rich beyond Charlie’s wildest imagining— and although he comes to her rather than summoning her to him, he twists the whole of Santa Rosa around his finger upon his arrival as effectively as any newly enthroned lord of the manor. Charlotte, for her part, recapitulates the whole Gothic heroine evolution, from initial infatuation through growing suspicion to mortal terror, except that she then takes matters into her own hands in a way that few of her predecessors in the genre were ever allowed to. (Come to think of it, there’s a case to be made that Charlie Newton is the great-grandmother of all Final Girls!) The oppositional attraction between the two Charlies takes on a perverse overtone, however, because they’re related to a degree that ought to put romance entirely out of the question. Hitchcock plainly understood that, too, and reveled in it, because he does everything in his power to make them look like the sort of amorous cousins that were a mainstay of Gothic fiction in its original, 18th-century formulation. Again the Hays Code prevented anything too outré from coming of that, but it’s incredible that Hitchcock got away with as much as he did. I’ve read that the director himself considered Shadow of a Doubt to be his best film. It’s certainly the best that I’ve seen, and the best illustration of his instinct for outsmarting the Hollywood system as well.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact