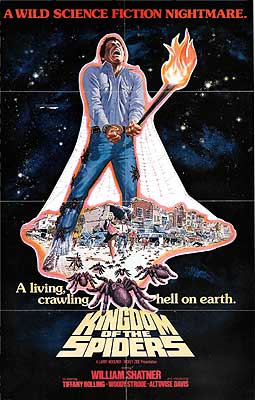

Kingdom of the Spiders (1977) -**½

Kingdom of the Spiders (1977) -**½

Rather to my surprise, it turns out that I misremembered Kingdom of the Spiders almost completely. Then again, when I last saw it 30-odd years ago, I didn’t yet have the broad experience with 1970’s animal-attack movies that I have today, so it probably makes sense that I wouldn’t have recognized this one for what it was. You see, you can’t just assume (as I evidently did back then) that the species of animal running amok is the salient characteristic of an animal-attack flick. Rather, there were about four major strains of these things in the 70’s, and within each of them, a wide variety of threats were at least theoretically possible: one species or many; ordinary, mundane beasties, or freaks of either nature or science; single, immense man-eaters, or hordes of smaller creatures that are deadly only in concert. And of course, however separate the strains might have been at their inception, cross-fertilization and hybridization began almost immediately, so that you very quickly end up with films— like Kingdom of the Spiders— that look like one thing on the surface, but turn out to be something else again upon closer inspection.

The oldest and most basic sort of animal-attack movie treats the animals as a sort of living natural disaster. Although there’s certainly the possibility of human death in these films, perhaps even on a mass scale, the important thing is that the animals’ activities are disrupting or threatening to disrupt the orderly business of civilized life. They’re destroying crops and livestock, making incursions into human settlements, maybe even overrunning entire cities. But troublesome as that may be for us Homo sapiens, these movies don’t present the animals’ behavior as aberrant for their species, except insofar as they might be responding to novel environmental pressures. They’re just doing their thing like they always have, but emergent circumstances have made “their thing” a danger to their human neighbors. The Naked Jungle is probably the type specimen here, and the formula seems to lend itself especially well to movies about swarming bugs. By the 70’s, that mostly meant endless extrapolations on the menace of killer Africanized honeybees, although ants, spiders, locusts, and even baby snakes got in on the action once in a while.

Then there’s the Mother Nature’s Revenge variant. Arguably there’s an element of this in all animal-attack films, since the whole point of the genre is the forcible reintegration of humanity into the cotillion of predator and prey, but I mean specifically the kind of killer-critter flick in which animals suddenly start engaging in uncharacteristic behaviors, seemingly going to war against human dominion over the biosphere. Mother Nature’s Revenge movies often have an overt environmentalist message, but they can get along just fine without one. Also common but not universal in this strain is the idea that the altered animals are responding to, or were created by, some particular act of human interference with the natural order. Consequently, Mother Nature’s Revenge tends to converge on the monster movie formula more generally, with the animals often being mutants, a newly emergent species, or the product of genetic engineering. Occasionally, however (like in Squirm), the inciting incident is mostly beyond human control— and in the progenitor of the lineage, The Birds, there’s no explanation for the animal uprising at all.

The remaining two strains are each rooted in the success of one particular film. Willard gave rise to a slow trickle of movies in which killer animals do the bidding of a human with whom they share a preternatural bond, while Jaws initiated a cycle of ripoffs so fecund that it spread beyond the boundaries of the animal-attack subgenre to include oddities like Gums (in which the “shark” is a cocksucking mermaid) and The Car (in which it’s literally the Devil’s hotrod). The Jaws lineage especially is defined by recurrent story beats and character types, including a benevolent authority figure beholden to a venal and possibly downright corrupt one, an expert to whom the latter authority fatefully refuses to listen, and a business venture or moneymaking opportunity that would be ruined if the presence of rampaging beasts were officially acknowledged. And that, at last, brings me back to Kingdom of the Spiders. All this time, I’ve had it pigeonholed incorrectly as a bee-movie spinoff in the disaster mode, when in reality it’s a Mother Nature’s Revenge flick riding on an extremely degenerate Jaws chassis. Although Kingdom of the Spiders gives short shrift to its Quint and Mayor Vaughn analogues, both are unmistakably present, while the really dispositive element is the county fair standing in for Amity’s Fourth of July weekend.

Smallhold Arizona cattle-rancher Walter Colby (Woody Strode, from Ravagers and Scream) has his eyes on the prize for dairy calves at this year’s county fair, scheduled to be held in just a few days in the little desert town of Verde Valley, somewhere in the orbit of Prescott. Just about all of Walter’s net worth is tied up in his herd and grazing land, so he could really use the $1000 cash money that a win would entail. His wife, Birch (Altovise Davis), and his neighbors (to the extent that anyone has neighbors in a region of such low population density) all agree that Walter’s is the calf to beat, too, so it’s a hell of a blow to Colby’s hopes and plans when the animal in question suddenly falls gravely ill. We’re talking paralysis, muscle tremors, foaming at the mouth— a bad scene all around. The rancher’s worst fear, naturally, is that the calf has some communicable disease that will require the quarantine and culling of his herd, but Dr. Robert “Rack” Hansen (William Shatner, of The Devil’s Rain and American Psycho 2), the Verde Valley veterinarian, assures him that there’s no need for such drastic measures just yet. The fact is, Rack has never seen an animal sick like that before, and he wants a second opinion from somebody at the university before he jumps to any conclusions. Colby never quite stands down from his fretting, but Hansen’s assurances come as a major relief to Mayor Connors (Roy Engel, from The Flying Saucer and The Magnetic Monster), who plausibly figures that any disease outbreak serious enough to require a quarantine of Walter’s herd would also force the shutdown of the county fair. That fair is way too important to Verde Valley’s businessmen for Connors not to greet such a prospect with horror.

The calf is dead by the time Hansen hears anything back from his academic colleagues, and the response he finally gets suggests that things are only going to get weirder and worse for Verde Valley from here. Rack sent the university a blood sample from the afflicted animal; in return, the university sends him an entomologist! Her name is Diane Ashley (Tiffany Bolling, from The Centerfold Girls and The Candy Snatchers), and her sex naturally means that she and Hansen are destined to spend the rest of the film enacting the exasperating courtship ritual of the unapproachably independent Liberated Woman and the unreconstructed Male Chauvinist Pig, but set that aside for the moment— Diane surely wishes she could. Ashley is here because the blood from Colby’s calf was full of spider venom. There was so much of the stuff, in fact, that not even a bite from the largest known tarantula species could account for a fraction of it. The only way for an animal that size to show that concentration of venom would be if it had been bitten by hundreds of spiders, and mass attacks are something that tarantulas simply don’t do.

Ashley has Hansen take her to the Colby ranch after she examines the refrigerated carcass herself, and they arrive just in time to witness Birch’s discovery that the family dog has died every bit as strangely and suddenly as the calf. Diane thought to bring along a quick-and-dirty test kit for tarantula venom, so it takes only a few minutes to establish the cause of death. That’s when the Colbys mention the “spider hill.” Now I’m sure you’ve never heard of a spider hill before, for the completely understandable reason that there’s no such thing. A couple dozen weirdo spider species spin big-ass apartment webs, and manage to live in them together without eating each other, but not a spider on this planet teams up to build earthworks like an ant or termite colony. For once, though, that’s the entire point. Like the cooperative attacks on animals too large for an individual spider to eat, the massive mound of interconnected tarantula burrows out behind Colby’s cattle pens is something that nobody has ever seen before.

In between fending off Rack’s thuddingly blunt attempts at flirtation and finding herself dragged against her will into a triangular configuration with him and his brother’s amorous widow (Marcy Lafferty, who in those days was Shatner’s real-life spouse, and appeared alongside him in Impulse and Star Trek: The Motion Picture as well), Ashley somehow finds time to develop a theory about what’s making the local tarantulas behave so strangely. She suspects that the farmers and ranchers in and around Verde Valley have so saturated their land with pesticides that the spiders (themselves immune to DDT and the like) have found it impossible to survive on their usual prey. They’ve got to eat something, though, so they’ve started collaborating to bring down bigger game. On their next visit to the Colby ranch, Ashley and Hansen get to see the spiders kill Walter’s bull, which throws an entirely new and altogether more alarming light onto the situation. Spiders that can bring down a full-grown bull could obviously do the same thing to a human no sweat, so neither whitecoat raises the slightest fuss when the Colbys set fire to the nest.

The trouble, as Ashley and Hansen discover the next morning, is that there are plenty more like it out in the surrounding desert. The implications for the county fair should be obvious, and Connors, ignoring professional advice as his sort always does in these movies, hires a cropduster known as “the Baron” (Whitey Hughes, of Black Samson and The Bees) to spray poison on the nests— the same kind of poison to which Ashley has already determined the spiders are immune. So not only does the Baron’s bug-bombing not solve the problem, but it creates several new ones when the pilot discovers, in midair, that his cockpit is full of tarantulas. The Baron loses control of his toxin-laden aircraft, flies it over half of Verde Valley with the sprayers spewing all the way, and crashes it into the gas station at the center of town. Inexplicably, even that isn’t enough to make Connors pull the plug on the fair, which the spiders interpret as the ringing of the dinner gong. They swarm into Verde Valley by the millions, attacking everyone and everything in sight.

From a logistical point of view, making a movie about killer bees is relatively easy. Bees live in colonies numbering scores of thousands, they’ve been domesticated for untold centuries, and normal moviegoers can’t tell the difference between Africanized honeybees and the ordinary European variety. All you have to do, then, is to get a few beekeepers on the phone, and rent a couple of their hives— and you can even get away with not using real insects except in the closeups, since bees are too small to register as individual creatures at most camera ranges anyway. Nothing like that will work with tarantulas, however. For one thing, there’s no commercial tarantula-keeping industry apart from whatever network of specialized bug-wranglers exists to serve the needs of movie and TV studios. Those people know their value, and charge accordingly. For another, tarantulas are solitary creatures— so solitary, in fact, that their main interest in each other outside of mating season is as potential prey. Even if you find someone with tarantulas for hire, in other words, they’re unlikely to have more than a handful of them in stock. And perhaps most inconveniently of all for cinematic purposes, tarantulas are big enough that you can spot the difference between a real one and a fake at a surprisingly long distance. The producers of Kingdom of the Spiders devised an ingenious solution to those problems, however. No sooner did they arrive in Sedona, Arizona, than they put out a $10-per-cephalothorax bounty on live tarantulas, ultimately getting some 5000 of the things from enterprising locals. That was rather its own hassle, since each bug had to kept in its own private container to prevent it from eating its fellows, but there’s no gainsaying the visual impact it makes when hundreds of patently living arachnids go skittering down the streets and across the scrub-lawns of Verde Valley. Not much about Kingdom of the Spiders works the way it was supposed to, but the bugs themselves surely do.

Otherwise, Kingdom of the Spiders is a fairly silly film, which cares too much about too many of the wrong things. The “Will they or won’t they— but Jesus Christ, why would they?!” romantic subplot concerning Hansen and Ashley is tedious in the extreme, although its reasons for being so are a tad more interesting than usual. The standard reactionary insistence that no self-directing career woman could possibly resist the allure of an old-fashioned macho man is obnoxious, of course. Shatner’s self-impressed, dick-swinging smugness is like a bleary, sixth-generation Xerox of Captain Kirk as misinterpreted by people who haven’t seen an episode of “Star Trek” since it went off the air the first time, and it’s impossible to imagine a woman of Diane Ashley’s background and accomplishments wanting anything to do with him. But the rote Battle of the Sexes stuff is less irritating for once than the simple fact that Hansen and Ashley’s contrived sexual tension detracts from Rack’s much more honestly fraught relationships with Terry and her preschool-age daughter (Natasha Ryan, from The Day Time Ended and The Entity). They, after all, share his culture and values, and the big obstacle to their happiness together seems to be Rack’s unspoken fear that a doctor can’t measure up to a rancher in a cowgirl’s, however adept he might also be at riding a horse or roping a steer. Meanwhile, the ritual genuflections toward Jaws— the county fair, Mayor Connors, the Baron’s doomed spider-spraying mission— similarly take away from the more compelling and original story that Kingdom of the Spiders keeps trying and failing to tell via the investigation into the nature, origin, and potential future of Verde Valley’s lethally strange tarantulas. Every time this movie settles for aping Jaws, it puts on hold the less cerebral, more rootin’-tootin’ riff on Phase IV that keeps threatening to break out, which I for one would much rather have watched than the film we actually got. Also, a Phase IV clone could have supported the inconclusive ending that

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact