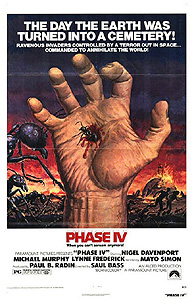

Phase IV (1974) ***½

Phase IV (1974) ***½

Ants are truly amazing creatures. An individual ant, so far as anyone can determine, is entirely mindless, yet the complexity of their societies rivals anything that we humans have devised. Ants are master builders. They cultivate food crops. They raise livestock. They wage war and practice slavery. They are able to communicate elaborate instructions to one another through a combination of gestures and scent chemicals. In short, nearly every practical feature of human societies finds its analog in that of at least one species of ant. But whereas our social achievements are mainly the product of culture, consciously or unconsciously taught by one generation to the next, ants do it all by instinct alone. It is this awesome fact, I believe, that has led so many authors and filmmakers over the years to speculate about what might happen if some environmental change were to occur so as to put humans and ants into direct competition. Most of the time, this means little more than making the ants big enough to pose a direct threat to human life, as in Them!. Occasionally, though, someone will try the more thoughtful approach of leaving the ants at their natural size and giving them intelligence instead. Phase IV, one of my longtime favorite 70’s sci-fi movies, is probably the best example of this latter strain. Those with short attention spans will find it rough going, but anyone who enjoyed The Andromeda Strain or Colossus: The Forbin Project owes it to themselves to have a look.

As the movie opens, something strange is going on in space. Screenwriter Mayo Simon doesn’t say precisely what it is, but the special effects representing it seem to depict some combination of solar flare activity and an odd conjunction of celestial bodies. Regardless, scientists all over the world are certain that the big cosmic light show is going to have repercussions on Earth— they just don’t know what form they’re going to take yet. In fact, even when the anticipated effect occurs, it nearly goes unnoticed “because it [happens] to such a tiny, insignificant creature.” Pretty much the only person who does notice at first is an eccentric and somewhat misanthropic entomologist named Dr. Ernest Hobbs (Nigel Davenport, from Peeping Tom and No Blade of Grass). The first signs may look innocuous to the layman, but Hobbs knows enough to be worried when he sees ants of different species in Arizona that are usually intensely antagonistic toward each other setting aside their traditional hostilities and cooperating. Even those who are less familiar with the ways of the family Formicidae start to worry when creatures that prey on ants start disappearing from the neighborhood. Before long, the strangely purposeful ants start making life so difficult for the local ranchers that the government orders an evacuation of the affected region, and approves funding for Dr. Hobbs to set up a laboratory out in the desert with the aim of figuring out just what has happened to the insects and how they might be stopped.

This is the plan. Hobbs’s laboratory consists of a small geodesic dome located in the part of the desert where the changed ants have most recently erected their eerily skyscraper-like hive-towers. The lab is protected by a ring of massive sprinklers for several types of powerful pesticide, and is equipped inside with as much state-of-the-art electronics as can be crammed into it. There isn’t a lot of room for habitation, so Hobbs will employ but a single assistant, Dr. James Lesko (Michael Murphy, from Count Yorga, Vampire and Shocker). Interestingly enough, Lesko is not an entomologist like Hobbs. His training is in cryptology— code-breaking. As you can probably guess, the idea is that Lesko will study the actions of the ants in an effort to determine whether or not they have developed a true language, while his partner attacks the problem from a purely biological perspective. If the ants really are talking to each other, then it just might be possible for us to talk to them. In order to get a completely free hand, however, Hobbs will need to make sure that everyone nearby really has evacuated like they were supposed to. For the most part, all is well on that front. But one family of small-hold farmers, the Eldridge clan, seems never to have gotten the notice. To some extent, this is to the scientists’ advantage; heading out to the farm to give old man Eldridge (Alan Gifford, from Devil Doll and The Legend of Nigger Charley), his wife Mildred (Helen Horton, who provided the voice of the computer in Alien), and their granddaughter Kendra (Lynne Frederick, of Vampire Circus and Schizo) the evacuation order gives Hobbs and Lesko a chance to interview people who have seen the ants in action. What they learn is not encouraging. The ants have become such a danger that Eldridge has felt compelled to surround his land with a gasoline-filled ditch. Nevertheless, the Eldridges are not happy to hear that they’re supposed to be evacuating, and for a moment there, it looks like Mildred is about to get all Montana Freemen on the scientists’ asses. Hobbs and Lesko take their leave of the farm after a short while, and return to the lab.

The biggest problem confronting the two whitecoats is getting the ants they’re supposed to be studying to do anything worthy of study. After most of two weeks (the government bean-counters to whom Hobbs is ultimately responsible somehow got it into their heads that the project would take only that long), there’s still nary a sign of activity from the little bastards. Eventually Hobbs gets tired of waiting, too. He steps outside of the lab with a flare-gun in his hand, and uses it to blow up all six of the nearby hive towers; that should get the ants busy. And indeed it does. They swarm against the lab by the millions, and are repelled only when Hobbs turns on the pesticide sprayers. Not only that, they launch an attack on the Eldridge farm before the family has a chance to escape. Through a stroke of luck so bad you know some god must be mad at them, the Eldridges flee to the Hobbs lab, and make it there just in time to get hosed down with super-powerful bug spray themselves. Only Kendra (who had the good sense to seek shelter in the basement of one of the abandoned houses beside the lab building) is alive when Hobbs and Lesko go outside to reconnoiter the following morning.

The ants have lots of tricks up their sleeves, though, and the advantage rapidly shifts back to them. By having her workers feed her— at the sacrifice of their own lives—controlled doses of the pesticide, the queen is able to produce a new generation of workers and soldiers who are immune to its effects. (Note, incidentally, that the “queen ant” is really a pepsis wasp wearing a prosthetic abdomen modeled on that of a queen termite. Actual queen ants aren’t nearly so impressive, looking basically the same as the workers, but three or more times their size.) These poison-proof ants spend the next night surrounding the lab with small mounds whose slanting upper surfaces have been polished to reflective smoothness. When the sun comes up, Hobbs, Lesko, and Kendra find themselves in a remarkably effective solar-powered oven. The scientists are able to destroy some of the reflector mounds with ultrasound, but the temperature within the lab climbs above 90 degrees (the temperature beyond which the computer that controls all the rest of the equipment won't function) before they can get all of them. Once the ants short out the air conditioner, too, the scientists are helpless to do much of anything at all except during the couple of hours before each dawn. And after Hobbs manages to get himself stung by one of the ants, Lesko may as well be on his own in figuring out how stop them— their venom causes a high, delirium-producing fever, to which the older scientist succumbs after just a few days.

A lot of people lump Phase IV in with the Mother Nature’s Revenge movies that were being made at about the same time, but I don't really think that's quite appropriate. There’s no revenge going on here, nor anything that would allow a person to say that we brought it all on ourselves— hell, there isn’t even any toxic waste lying around for the ants to eat! What we’re dealing with here is just the emergence of a new species capable of out-competing us in the great struggle for survival. For that very reason, Phase IV seems like much more serious and intelligent a movie than Frogs or Prophecy. The absence of much in the way of showy special effects is another big point in this movie’s favor, indicating as it does director Saul Bass’s confidence that the screenplay he was working from was strong enough to stand scrutiny without such things to distract audience attention. Or at any rate, that’s how I score it; it’s also a big part of the reason the short attention span crowd are going to be squirming uncomfortably in their seats before the first hour has passed. If you’re asking me, though (and if you aren’t, then why the fuck are you still reading this?), Phase IV gets along just fine with barely any action. The entire point here, after all, is that the challenge posed by the intelligent ants is one that can’t really be met with firepower. This isn’t war we're talking about, but evolutionary change. Modern man is so far removed from the days in which he existed at the same level as the rest of the biosphere that most of us have never stopped to consider what it would be like if we had meaningful ecological competition. By positing a rival for humanity that is too small to be hunted, too adaptable to be poisoned out of existence, and at least potentially too ubiquitous to be quarantined, Phase IV forces just such a consideration. Meanwhile, the fact that it ends before the two species have come to grips with each other on a large scale leaves open all of the questions that it raises. We never get more than the vaguest hints as to what the ants’ real agenda might be regarding humankind, nor is any conclusive answer forthcoming to the question of whether meaningful communication is possible between them and us. Though the ants are apparently comparable to humans in terms of intelligence, the vast social and biological differences between the species might preclude communication on any but the most concrete and tangible subjects. It isn’t even clear whether all the ants in the changed colonies are intelligent, or whether sapient queens are directing swarms of workers that are just as mindless as ever (although there are a few vague clues suggesting that the ants may have developed a new caste in their society that is as specialized for thinking as the soldier caste is for fighting). A lot of filmmakers seem to have lost track of this in recent decades, but there’s a reason why its thinner-skinned fans prefer to call science fiction by the rather more pretentious name of “speculative fiction”— the shit’s supposed to make you think! Phase IV does, and that’s a hell of a lot more than you can say for most movies about killer bugs.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact