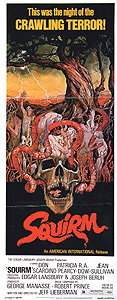

Squirm (1976) **

Squirm (1976) **

Needless to say, there is an almost infinite array of disastrous mistakes that a person can make while shooting a horror movie, but there are a few broad categories of error that seem to recur with remarkable frequency. After the very general “hiring complete idiots to act, edit, handle the special effects, etc.,” I’d say the screw-up I’ve seen most often is the conflation of “icky” with “scary.” This happens especially frequently in animal-attack movies or films that feature animal-derived monsters. To give you some idea of what I’m talking about, consider scorpions and maggots. Scorpions are at least potentially scary. Not only are they weird-looking, relatively exotic, and surprisingly hard to kill, they actually are fairly dangerous— lethally so in the case of many tropical species. Maggots, on the other hand, are merely icky. Though even a lifelong entomophile like myself can’t help but regard them as vile, disgusting creatures, I also can’t bring myself to feel threatened by something that small which has neither stingers nor claws nor mandibles, and which not only lacks venom but wouldn’t even be poisonous if you ate it. You know what else isn’t scary? Worms. In fact, the non-scariness of worms is so obvious that it’s scarcely surprising that it took until 1976 for some dumbass to try making a horror movie about them, or that no other worm-themed animal-attack flick seems to have been made since Squirm arrived on the scene.

At least writer/director Jeff Lieberman picked some decent worms. Our setting is the tiny town of Fly Creek, Georgia, which means none of those sissy little earthworms we’re used to seeing throughout most of the country. No, the worms of Squirm are bloodworms and bristle worms, both of them extra-large, extra-gross annelid species with tiny, curving fangs. (And to judge by the outrageous squeaking noises on the soundtrack that always accompany their appearance, Lieberman gets his worms from the same supplier as Lucio Fulci.) As for what turns them vicious, well… let’s just say Lieberman could have tried a little bit harder. A severe summer thunderstorm floods the already swampy land surrounding Fly Creek, blocks roads with fallen trees and standing water, severs telephone lines, and even brings down a high-tension electrical tower. The torn electrical cables pour hundreds of thousands of volts into the ground, where the flooding of the soil conducts the electricity throughout the land for miles around. And for no real reason at all, all that current has the effect of making every worm in Fly Creek turn crazy and mean.

So it’s a good thing most of our protagonists live next door to a bait salesman’s worm farm, eh? Geri Sanders (Patricia Pearcy, from Delusion and Cockfighter) is simply bursting with anticipation at the impending arrival in Fly Creek of a young man from New York, whom she met at an antique show out of town some months ago. Her sister, Alma, (Fran Higgins), has been keeping herself amused by making salacious comments, while her mother, Naomi (Jean Sullivan), has been worrying herself sick. No one ever bothers to explain why Mom is so twitchy, but the complete absence of any sort of father figure in the Sanders household (nobody even mentions the girls’ other parent) introduces the possibility that the man was a deadbeat who left Naomi in the lurch with two kids to take care of, while he went off to embark on an adventuresome new life banging redneck skanks. But this boy whose advent Geri is so fervently awaiting is coming to town by bus, which is going to present some problems, what with all the roads into Fly Creek flooded out or otherwise blocked as a result of last night’s storm. Thinking fast, Geri asks Roger Grimes (R. A. Dow), the son of the worm farmer next door, if she can borrow his truck. Roger agrees, on the condition that she be very careful with the crates in its cargo bed.

Right about then, Mick the Gawky New Yorker (He Knows You’re Alone’s Don Scardino) is learning about the roads being fucked up. When the bus driver announces that he’s going to have to turn around and backtrack to the last intersection, Mick pipes up, asking to be let off right there with directions to Fly Creek. Thus it is that he begins wending his way through the swampy forest, heavily laden with a ridiculous surplus of luggage. Geri finds him not five seconds after he falls up to his armpits into a muck-hole.

Now before Geri left, her mother told her to pick up a block of ice on the way home (to compensate for the refrigerator that isn’t working because there’s no electricity in Fly Creek at the moment), so Mick gets no downtime before receiving his first taste of small-town southern living. While Geri is at the store picking up some ice, Mick heads over to a little diner to order— that’s right— an egg cream. Since no one who lives outside a 30-mile radius of New York City has any idea what an egg cream is (and isn’t likely to figure it out without help, as the recipe involves neither eggs nor cream), Mick is met only with dull incomprehension from the waitress. He’s also just erected a huge neon sign over his head that reads, “City Boy— Not to Be Trusted.” And sure enough, when a big-ass bloodworm turns up in what passes for his egg cream (after he explains how to make one) and he reacts with understandable horror, Sheriff Reston (Peter MacLean) takes him for a practical joker and gives him the whole Corrupt Redneck Cop act.

So how did that bloodworm get into Mick’s drink? That’s easy— what do you think was in those crates in the back of Roger’s truck? Oh, and allow me to emphasize the “was” in that sentence— all 100,000 of the things are gone by the time Geri returns the truck to Roger and his belligerent dad, Willie (Carl Dagenhart). This does not, however, mean that the worm rampage which this movie’s creators have promised us is going to be starting any time soon. Instead, Lieberman and company proceed to waste oodles and oodles of our time on contrived subplots. First there’s the “what happened to the old antique dealer who seems to have gone missing, and what’s up with that skeleton in his backyard?” subplot. Then there’s the “Sheriff Reston doesn’t believe Mick and Geri when they come to him with evidence of a murder, and threatens to put Mick in jail” subplot. This is followed in short order by the utterly pointless “Roger loves Geri but she doesn’t love him, so he tries to rape her on a fishing trip” subplot. Each one offers tantalizing hints of man-eating worm action (Roger gets his comeuppance thereby, in fact), but not enough to make me care. Come to think of it, when the worms finally do come out in force after sundown (worms don’t like light very much) to eat virtually the whole town of Fly Creek, it still isn’t enough to make me care!

Were it not for the couple of brief peeks it allows us at Patricia Pearcy’s strangely unpigmented nipples, I’d swear that Squirm had been made for TV. It’s got that same flat cinematography, that same minimally acceptable but also completely lifeless acting, that distinctive music that until now I can’t recall having heard anywhere else. And also like most 70’s TV horror flicks, it’s too restrained to be really engaging, yet is made with a degree of colorless technical competence that makes it difficult to have any really strong negative feelings about it either. Frankly, that’s the most disappointing thing of all about Squirm. If a movie about killer bloodworms can’t be enjoyably awful, what point is there in watching it?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact